There are roughly 17,000 pages worth of Charlottesville property deeds sitting at the bottom of the Albemarle County Courthouse, and freelance journalist Jordy Yager plans on analyzing each and every one of them. In these deeds, which date back to the early 20th century, Yager has found racial wording that essentially prevented future homeowners from selling to people of color, creating a perpetual loop of segregated housing in the City.

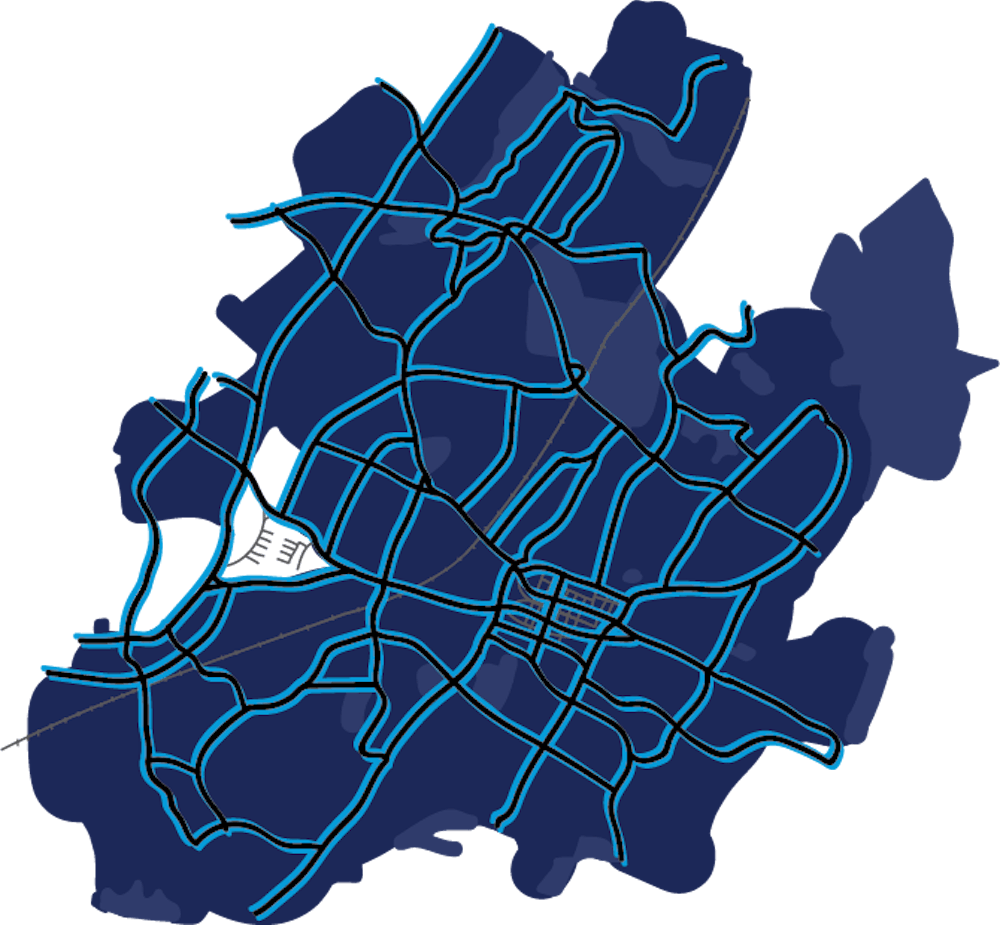

Yager plans to create an interactive map of the City’s housing discrimination, giving the public a better way to learn about its history. The Charlottesville Area Community Foundation, an endowment that funds initiatives to enact positive change in Charlottesville and surrounding areas, has granted Yager with $50,000 to create the map.

The motivation behind this project came from Yager’s observation of racial disproportionality between black and white children within Charlottesville in areas such as the criminal justice and education systems. After finding this data, he became determined to find out why.

“What [has been proven] by looking at mass amounts of data all over the country is that one's environment, where one lives, is the number one predictor of where one ends up in life,” Yager said. "If where we live is the predictor of all of our outcomes in life … then why do we live where we live? What has dictated that? So that's how I started looking at the history of housing in Charlottesville."

To help with data collection, University students in the class HIUS 3853, “From Redlined to Subprime: Race and Real Estate in the U.S.” taught by African-American Studies Assoc. Prof. Andrew Kahrl, were brought in. Using the app Adobe Scan, students were assigned to two-hour shifts in the basement of the courthouse in which they scanned and uploaded the deed pages one by one. Third-year history major Thomas Joyce was part of the team of students.

“It gave me a really good experience with being hands-on with actual real documents,” Joyce said. “Most of the classwork that you do in high school and even college, it’s with first-hand sources, but they're photocopies. I was actually holding these deed books that were from 1910 and 1920s.”

Using Geographic Information Systems, applications used to analyze and present geographic data, Yager will input each property onto an electronic map, creating a layer of Charlottesville properties that were racially restricted.

The exhibit will be placed at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, where visitors will be able to move through the touch-screen exhibit, looking at any property and the story that comes with that property.

“It’s so easy to be a visual learner,” Joyce said. “The information that we're getting from these thickly-worded documents to create a map … [it makes] the segregation so tangible in that way.”

According to Yager, the base map of racial covenants is just the beginning. This “layer” will be accompanied by additional information, informing visitors of infrastructure investment and neglect, property values, stop and frisk incidents, as well as health and education disparities. Together, these layers will work to tell the broader story of housing discrimination in Charlottesville.

Though data analysis cannot fully begin until more data has been collected, certain faculty and students around Grounds have started looking into the work that needs to be done. One such faculty member is Dayna Bowen Matthew, a human rights, law and public health sciences professor. Matthew, along with other researchers in the University and Virginia Commonwealth University, are collaborating with Yager to add black-white gaps in public health to the mapping project.

“We will explore how segregation in Charlottesville also meant blacks did not have equal access as whites in this city to clean water, clean air, indoor plumbing, heating, recreational spaces or decently built homes and therefore suffer disproportionately worse health outcomes that persist to even the present day,” Matthew said in an email.

By the beginning of next year, Yager’s plan is to have all of this information analyzed and presented together within the interactive map, ready for the public. For years after its initial debut in the Jefferson School, the expectation is for the data within the map to be dynamic, with the idea that additional research will continue to be added on in the future.

“Getting all of the technological and financial support to make that happen is going to be an ongoing challenge,” Yager said. “We have multiple sources and streams of data talking and interacting with one another in evolving ways, so it's not just static, it's not just sitting there."