“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

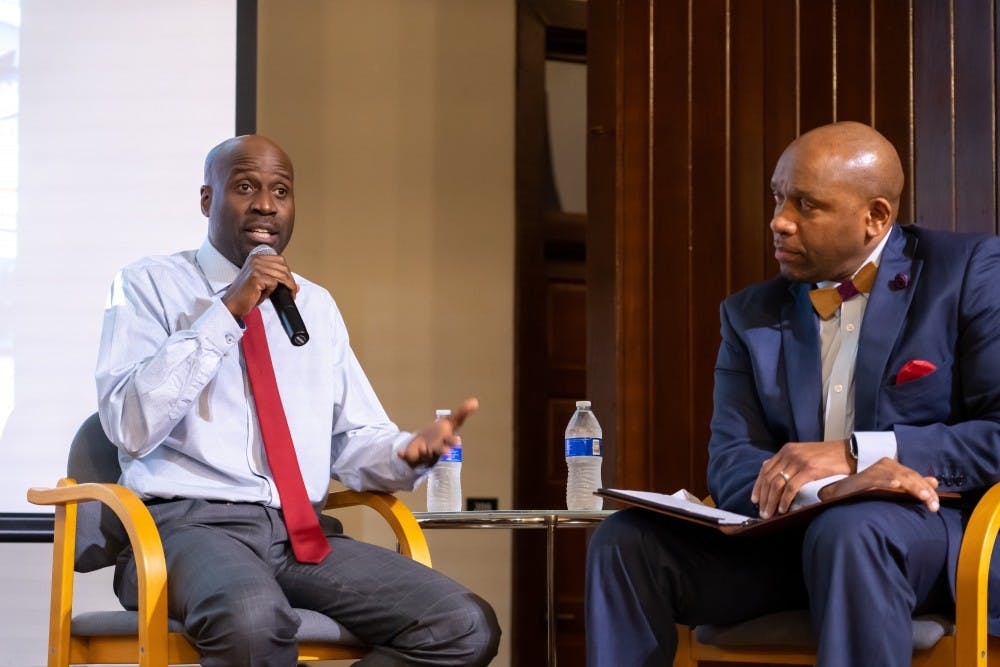

This quote from legendary American writer James Baldwin was projected on screen before artist Bayeté Ross Smith’s talk Wednesday evening at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. The event was accompanied by a Q&A panel with Kevin MacDonald, the University’s recently appointed Vice President of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. During the talk, Smith revealed that Baldwin is likely the greatest non-familial influence in his life.

Smith was introduced with a menagerie of labels and accomplishments, having defined himself with a multimedia art career that spans sculpture, photography, video and interactive technological elements. The distinguished Harlem-based artist started his career as a photojournalist in various cities along the East Coast and later decided to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree at the California College of the Arts.

“I like to use artistic license and be playful in terms of how I actually create the narratives and visual structures for these stories that I like to tell,” Smith said. He then described the importance of globally inclusive societies, and went on to emphasize the unique role the U.S. is primed to play. It’s one of the “few nations in the history of the world that actually has the ability to include people from cultures all around the world in its makeup.” These words would foreshadow the display of his work, which tackles the meaning of identity and multiculturalism in a society that struggles to understand them.

Smith showed a photo of his many cousins to outline his background and give an example on the issue of identity in America. “While we’re all black, we’re not only black,” he said. “Being black in America can mean and look like a lot of different things.”

Images then appeared on the screen from Smith’s photo series “Our Kind of People,” which displays horizontally-aligned collages of the same people presented slightly differently.

“Devoid of any other means or context for assessing the various alter-egos of these photos, the viewer will project their own preconceptions,” Smith said.

He gave an example where he asked observers to label the version of himself in the photographs they found most appealing. Most chose the suit. When asked to do the same for his white friend, many avoided the suit and chose a more casual outfit. Smith suggested that this might be due to stereotypes, where black men in hoodies are seen dangerously just like white men in suits who might be seen on the news having committed fraud or white-collar crime. Embedded in clothing, Smith suggests, is an extraordinary amount of identity tied with the ethnicity of the wearer.

Next, Smith displayed photos from “Taking Aim,” a bold series of images overlaying targets onto various portraits. Smith even made a version with his own likeness and asked people at a shooting range to practice on his image. He was curious as to why shooting targets always depict unrealistic caricatures when real violence and self-defense scenarios are so different. The uncomfortable proposition was spurred by what Smith described as a “fine line between recreational, condoned violence and deplorable, criminalized violence.” He illustrated with an example of a boxing match versus a street fight — two physically similar situations that are socially very different.

The evening’s most interesting surprises came when Smith detailed his video pieces. One piece, titled “Question Bridge,” featured a series of black men asking and answering candid questions about everyday life across five screens. Smith wanted to present these faces because he noticed that “black males were very prominent in media … but not present in the ways that can control and define them.” “Question Bridge” makes a case for itself as a portal to black male existence, with occasionally silly-seeming questions — like one about eating bananas and watermelon in front of white people, for example — being answered in serious and surprising ways. Smith said he hoped the series could function as a “window into black consciousness.”

Smith also worked with the PBS series “POV” and the New York Times on “Hyphen-Nation,” a video series that asks what makes someone American.

“Some people get to be born as Americans simply because of their backgrounds,” Smith said. “Others have a label to their American-ness,” hence the hyphen.

In the videos, an Indian woman described being called a terrorist in a CVS shortly after 9/11. A black Iraq War veteran talked about being in a vehicle with a white woman and getting stopped by a police officer. He was the one asked for identification despite being the passenger.

“It’s odd doing what you do knowing you’re fighting for your country and knowing you’re not owed the freedoms you were fighting for,” the veteran said.

Smith continued to present several other projects. “West 4th Street” was a video series with an interactive element, letting viewers choose between an age and racially diverse set of narrators telling the same true story, challenging them to make out which parts they empathize with based on the identity of the speaker.

He then showcased “Got the Power,” a welding, sculptural project built out of boomboxes that played local, community-centric music in installed areas, as well as some 360-degree videos made with POV that overlapped historical archival data onto real places in the modern day. The example shown narrated the story of Malcom X’s assassination while surround video explored the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where the shots were fired.

The evening concluded with the Q&A session, in which Smith hinted at a forthcoming collaboration with the School of Law for the Kings Against Violence Initiative. The partnership hopes to present rising legal minds with artwork like Smith’s so that they can be better citizens.

“If we can create impact and awareness around contemporary social issues with people during their legal training,” Smith said, “I think we can create a profound impact on social awareness as well as the implementation of policy.”

Smith summed up his artwork as an effort to make a global, multicultural society a true reality. For Smith and artists like him, identity is anything but a box to be checked.