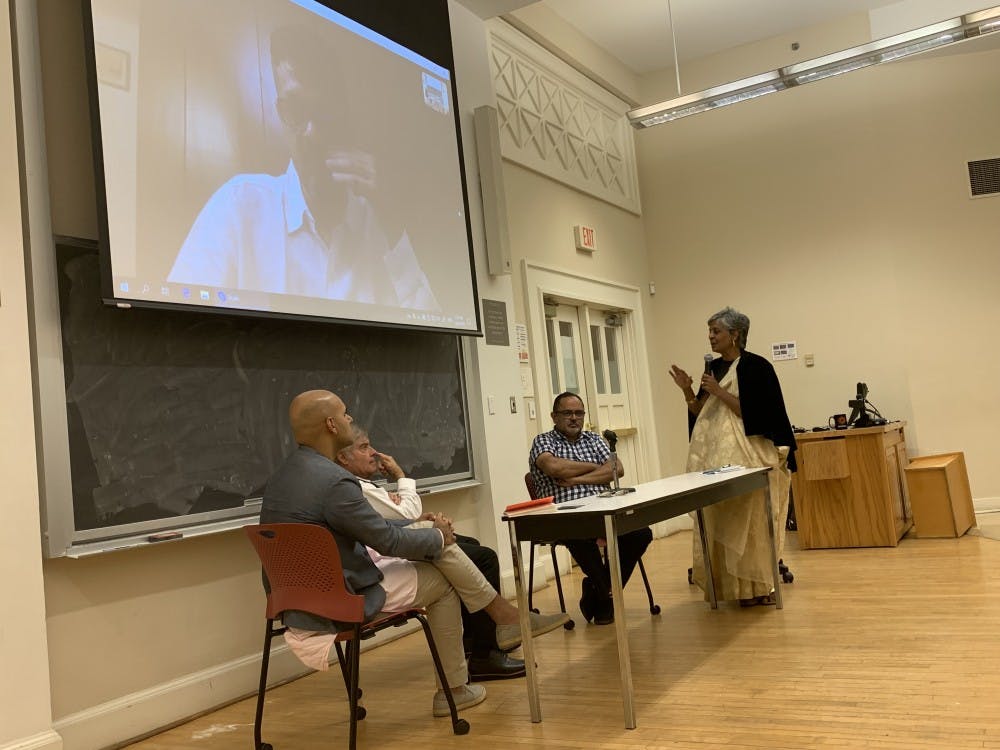

When Geeta Patel — professor in the departments of Middle Eastern and South Asian Language and Cultures and Women, Gender and Sexuality at the University — introduced Mumbai-based documentarian Avijit Mukul Kishore Wednesday night, she described his work as possessing an “incredible calm.” The film that was screened in Minor Hall on the first night of “Cinema, Architecture, Art: Envisioning Aesthetics, Politics, Citizenship and Personal Stories,” a festival of documentaries from India that Patel organized.

The film that opened the three night festival, which ran through Friday, was the 2017 documentary “Nostalgia for the Future,” which was co-directed by Kishore and his partner, Rohan Shivkumar. The two men — Shivkumar used Skype to join from India — joined Patel, School of Architecture professor Peter Waldman and University alum and former National Public Radio producer Bilal Quereshi. The central theme of the documentary and the event — which about 80 people attended — both revolved around the intersection between modernity, citizenship and architecture in India.

The film doesn’t necessarily embody calm in the relaxing sense — both directors describe how the inspiration for the film came from a shared anxiety they had as citizens of the nation. Rather, the calm in “Nostalgia for the Future” is in the way the camera is a patient yet active observer of the surrounding world. One of the first shots we see is of a boy blowing bubbles, with the camera following the bubbles as they drift out into the surrounding space.

The film is ripe with these lingering moments, using silence in a masterful way to ratchet up the viewer’s emotions. We see children gathering in grayscale as they pose for the camera and men smiling at the lens as they lean against a fence. Perhaps the spot where the pause was felt most was when the film led viewers on a sort of silent tour through the industrial-style Villa Shodan, a large concrete cube home designed by famed architect Le Corbusier. We move room to room, camera completely stationary, the only movement or change being lights turning on to illuminate the space. The series of frames seems to ask of the audience, “Who lives here?”

Kishore and Shivkumar invert common notions of house and home in this film. We think of our homes as things we own, giant hollow objects that we shape into a living space. “Nostalgia for the Future” paints the home as the architect, molding and designing the ideal citizen to inhabit it. In the beginning of the film, Kishore’s voiceover narration melds static and flute music, saying in Hindi, “Homes are machines that we live in” and “We hope to live up to the homes that we dream. We hope that our bodies will be worthy of inhabiting our homes.”

“If you look at ‘Nostalgia for the Future … [the film] is about different ideas of modernity in India as defined through the architecture of the home built over an almost 80 year period,” Kishore said in an interview with Arts and Entertainment prior to the screening. “So, it’s … that home is catering to different ideals of the human body. There is the body as imagined at different points of time by the Indian state, and by different people, by individuals as to what really constitutes a ‘modern’ person. And what is the kind of house that he or she would inhabit, you know? So it’s almost as if the body has to be worthy of that house, which is coming with a certain ideology.”

This concept of home over inhabitant is obvious in the way the documentary is filmed, with many of the scenes shot in ways that incorporate architectural elements — the camera peeks around corners, frames people in doorways and watches the retreating back of a man from the landing of a split-level staircase. The design of the home demands something of its occupant. One of the most striking examples of this comes when a woman is being filmed in a small kitchen. She reaches for a cabinet above her head, and an abrupt transition to a schematic diagram of a woman in the same position occurs. The kitchen, the heights of cabinets, the dimensions were all designed to fit the female form almost exclusively, illuminating the gendered construction of certain areas of the home.

This film is an exploration of the physical products of ideology throughout India’s history. From the historical perspective, audiences see how the concept of the home changed post-independence from Great Britain, and how the need for India to be seen as a progressing modern nation became paramount. This wanting to be seen as something different than the truth is apparent when examining the inherent queerness of the film, which goes beyond its being produced by men in a same-sex partnership.

“Especially when you watch [“Nostalgia for the Future”] ... there’s so much about performance and wanting to be somebody else,” Kishore said. “So, if it’s you wanting to deserve your house or wanting to be a certain way that you’re not, in many ways those are reflections on queer identity. So, it’s queer through performativity that the film ends up using. That way, I consider a more — in many ways — complex performance of queer identity, or acknowledgment of queer identity that just using the label based on subject.”

When asked what audiences ideally would take away from the screening at the University, Kishore had an almost immediate answer.

“Questions,” he said. “More than answers. Thoughts, experiences that stay with you.” Every part of the documentary was intentional, from the crackle of celluloid film to the rushing of string to the use of found footage and audio bits all melting together. The end result is something poignant, something that makes its viewers think and pause for just a beat before bursting into applause.

Correction: This article previously misstated that about 50 people attended the event. About 80 people actually attended, and this article has been updated with the correct figure.