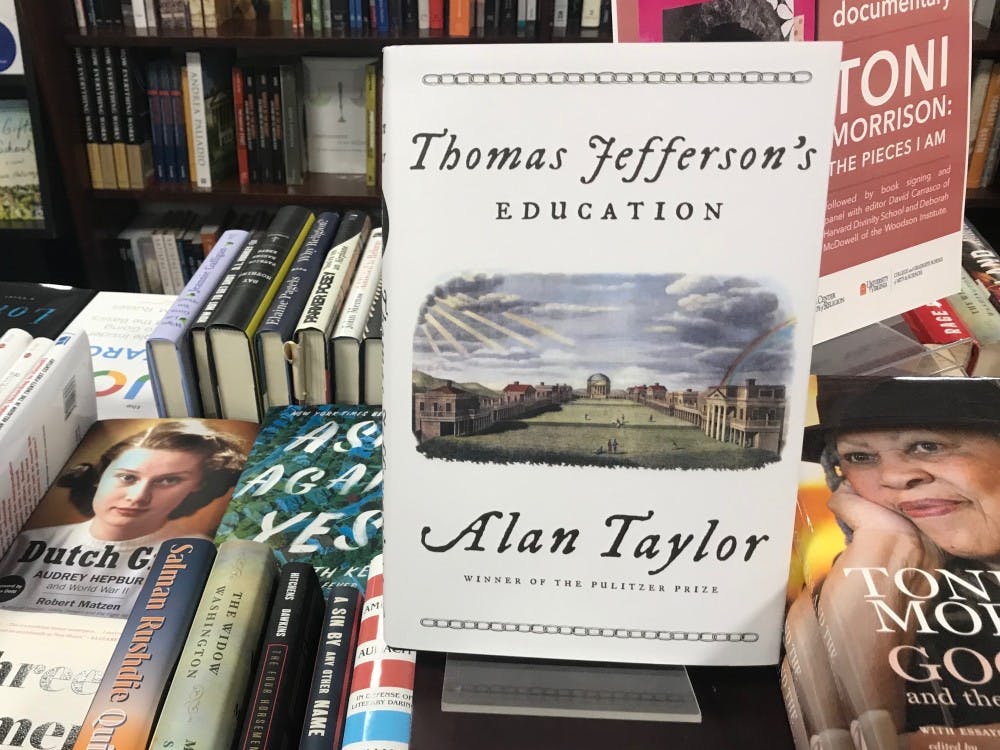

Alan Taylor, chair of the history department’s Thomas Jefferson Foundation and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner for history, officially released his new book, “Thomas Jefferson’s Education,” Tuesday. Taylor gives a detailed account of the University’s failure to actualize Jefferson’s idyllic views on education and its ability to promote generational reform — especially in regard to society’s exploitation of enslaved laborers, who built and maintained the University.

Taylor said that the University is increasingly involved in uncovering the full history of its founding legacy, adding that there are more courses taught on the University and Jefferson’s history with slavery than ever before.

Taylor also said that the University leadership — and the nation as a whole — tend to take inspiration from the emphasis Jefferson placed on democracy, progress, education and truth. However, Taylor added that his idyllic values did not preclude Jefferson from adhering to the reality of his time.

“The founders lived in a very different time and lived in a very different society … where women couldn't vote, where most African Americans were treated as property rather than as people,” Taylor said. “So Jefferson is not the only one doing this, he's part of the mainstream. And I think it's important for us to understand the society that the founders lived in rather than just think that they had the master key to solving all of our problems today.”

During a talk held at New Dominion Bookshop Friday evening, Taylor described to members of the Charlottesville community how the early University sustained the privilege held by the young white men of Virginia’s elite class.

Upon its opening in 1825, the University was the most expensive institution of higher learning in the nation and did not offer any scholarship due to lack of funds, which Taylor said was caused by the high cost of Jefferson’s design — a model run by the backroom “hotels” that used around 100 subcontracted enslaved laborers to cater to about the same number of students’ needs.

The students at the University were young men with a “prickly sense of honor,” Taylor said — they were those whose families could afford to be full-paying customers of the University, and they wanted to uphold the power structures that advantaged them, rather than reform society as Jefferson intended.

During the talk, Taylor focused on the case of Wilson-Miles Cary, who was Jefferson’s great-great nephew and a model of the chaotic and violent behavior that prevailed at the University. However, despite being kicked out of the University, Taylor notes that Cary still managed to become an influential member of Charlottesville’s society and eventually a member of the state senate in Maryland.

“This is also representative of all these young men who create so much chaos either at the College of William Mary, or at U.Va.,” Taylor said during the talk. “That eventually they will settle down, and they will move into their expected roles as the owners of plantations and the leaders of either Virginia, or in his case, Maryland.”

Taylor joined the University faculty in 2014, and he told The Cavalier Daily that in his time here he has seen its efforts to reconcile with its past.

“I do think that the University administrators are very open to discovering the full history of this institution, the good and the bad,” Taylor said. “And to understand that we have a responsibility to continue to improve the institution, and to make it more welcoming to everybody who comes here to study.”