Based on the remarkable life of Harriet Tubman, “Harriet” premiered at the Virginia Film Festival Saturday night at the Paramount Theatre. “Harriet” is part of the Race in America series presented by James Madison’s Montpelier and supported by Bama Works Fund, the Office for Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights and the Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the University.

Played by Cynthia Erivo, “Harriet” follows the journey of Araminta Ross, or “Minty,” as she transforms into the free “Harriet Tubman,” and the abolitionist “Moses.” These three names mark distinct phases in Harriet’s life as she transforms from an enslaved young woman to a relentless abolitionist with an undying call to rescue and free enslaved people.

In the film, Harriet attributes this empathy to the closeness of her enslaved life, revealing a complex relationship between formerly enslaved abolitionists and their born-free counterparts. The film explores this tension in scene between Harriet and Marie, her friend and inn-keeper, when Harriet emphasizes Marie’s position as being born free and never experiencing enslavement firsthand. When Marie apologizes in response, she defines boundaries in their friendship and promises to acknowledge her privilege as a born-free black woman. In this way, Harriet holds her colleagues accountable to consistently acknowledge their privilege, and further, recognize the reality of enslavement and abolitionists’ urgent duty to act.

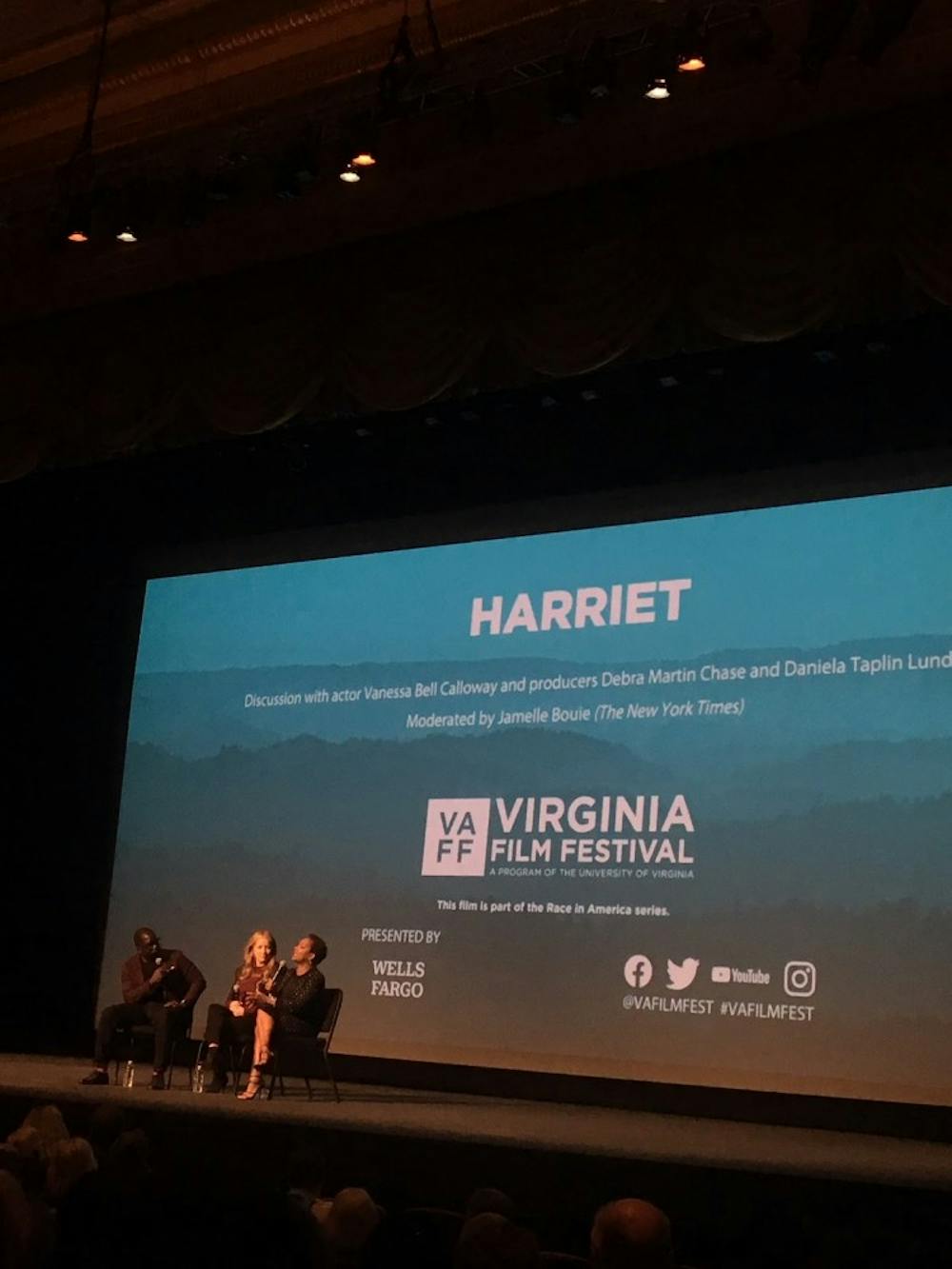

Following the film, producer Daniela Taplin Lundberg and actress Vanessa Bell Calloway, who plays Rit, Harriet’s mother, engaged in a discussion moderated by The New York Times writer Jamelle Bouie surrounding the film’s making in Virginia. As the entirety of the film was shot in Virginia, Lundberg and Calloway discussed the intensity of filming on plantations, as the film likely reflected true history that occurred there.

Lundberg expressed that it was “quite affecting” to film on former plantations in Virginia, such as Thompson’s Mill. She attributed the positive experience to plantation owners who dealt with the situation with integrity and wanted to help contribute to rectifying their plantation’s history of enslavement. “[The] only way we could have handled it were for the owners to be as open and honest as they were,” she said.

Although Calloway responded that she “couldn’t help but feel something,” she highlighted the importance of separating the history from the present moment and “us[ing] it for the better and not the worse.” For example, she explored the discomfort that her white colleagues felt in saying the n-word, expressing that the separation was necessary for the cast in acting out these racist and harmful relationships. Despite this separation, Calloway emphasized that it was impossible to ignore the synergy and energy that emerged from shooting on plantations. “When you’re in a scene, all the make-believe makes you feel some type of way because it was real,” she said.

Lundberg also highlighted the importance of Harriet’s unique faith in guiding her journey, stating that “it was the thing that told her her path.” Grounded in her faith, Harriet experienced premonitions that alerted her to danger and shifted her attention where it should be — freeing enslaved people in the South. In this way, Harriet’s faith enabled her to become a fierce leader, because she whole-heartedly believed she was helping achieve God’s mission through her work.

When discussing the origins of the film, Lundberg expressed how the screenwriters envisioned “Harriet Tubman as a badass,” and as “America’s first superhero.” Being the first film made about Harriet Tubman, the screenwriters aimed to tell the “story of a young woman who is real and a regular person.” Calloway expressed the courage needed to act in a situation like this, stating that Harriet had “the courage of many for many.” “Harriet” provokes its audiences to think, and has viewers leaving the theatre feeling empowered to act in the face of injustice.