For every first-year student, the first few weeks of the school year are full of meeting new people — and my experience was no exception. I met countless people in my dorm, in class and in club interest meetings. At the University, I’ve found that students tend to “break the ice” by bringing up school-related topics first. “How are you liking your time here?” and questions about majors and living situation are asked more often than questions like, “Where are you from?”

I’ve rarely been asked this. I suppose it could be because most students seem to be from in-state — especially “NoVa.” This led to incidents weeks later when I wound up surprising people by telling them that I’m not from Virginia — that I’m actually an international student from Japan.

This academic year marks my fifth year studying in the United States and using English in classes. Before the University, I had attended a boarding school in Pennsylvania. Since I had only attended schools in Japan prior to my education in the States, the transition period of learning a new language was challenging at first. At my boarding school, I was the only Japanese student in the entire student body.

Unlike many international students at the University, my time in the States has been without a community of students who shared the same cultural and linguistic background — where I could feel “at home.” I had no choice but to try and assimilate myself to these new surroundings. Now, I’m appreciative of what I had once considered a predicament. It allowed me to experience a complete immersion and resolved my language and cultural barrier.

Four years later, I’m achieving my dreams. I attend a very good school and have acquired a decent knowledge of English to the extent that some people cannot tell I am a foreigner. But at the same time, I’m facing a new problem — I’m forgetting my mother tongue.

This became most evident last winter when my parents finally convinced me to write New Year’s cards to my friends for the first time in years. Traditionally, people in Japan send cards only for New Year’s, instead of sending cards for Christmas and New Year’s. I bought about 20 postcards — enough to send to my friends from middle school in Japan. I positioned my pen above my card to write the most cliché greetings I could think of — but I couldn’t think of any.

This difficulty made me remember how long it had been since I had last written in Japanese. I don’t usually keep a diary, and I always text or email when I want to check in with my friends from home. For the past four years, there was simply no need for me to write in Japanese. Moreover, the use of Chinese characters in the Japanese language makes it even harder for me to restore my fluency with the language — there are literally thousands more Chinese characters you are expected to know when compared to the 26 letters in the Latin alphabet.

I also noticed that coming up with correct Japanese phrases in conversation takes more time. Whenever I go home for breaks, my family teases me about how I unconsciously incorporate the “Uh...” English filler into my Japanese speech. From this point on, the need to do something about my declining ability to use my native language has become a priority for me.

Several of my friends from home — including those who had studied in an American school like I did — tell me that I shouldn’t be too worried. In their experience, their Japanese completely returned after spending time in a school or work environment where they had to use the language. However, there are reasons why I cannot feel totally relieved to hear what they have said.

Throughout the past four years I have spent in this country, I’ve witnessed very little Japanese representation almost everywhere I’ve been — including on the West Coast. It’s been nearly a month since I arrived on Grounds, and I have yet to meet a single full-time student from Japan. The 2010 Census shows that despite a 43.3 percent increase in the overall Asian American population since 2000, Japanese American was one of the only Asian ethnic groups with a decrease in population.

Although education is the primary reason I’m in America, my long-term plan after graduation is unclear. The lack of certainty in when to — and frankly, even whether to — return home to work makes me particularly anxious about this diminishing part of myself. I think language will always play an important role in my cultural identity, so this issue needed to be addressed.

I’ve been calling my friends from home more often — not only to help restore my fluency with the language, but also to keep up with the many friendships I still cherish. Whenever I have free time, I also try to listen to a Japanese podcast instead of watching Netflix — though I admit sometimes I would rather be re-watching “House of Cards.” I also plan to do more to compensate for my declining familiarity with writing in Japanese. I intend to periodically send hand-written letters to my grandparents, which will make them happy.

I realized that because of my long-term commitment to learning the English language and applying it to my academics, I had nearly forgotten about a part of what makes me who I am. However, this year presents new opportunities for growth and change. Stay tuned, readers.

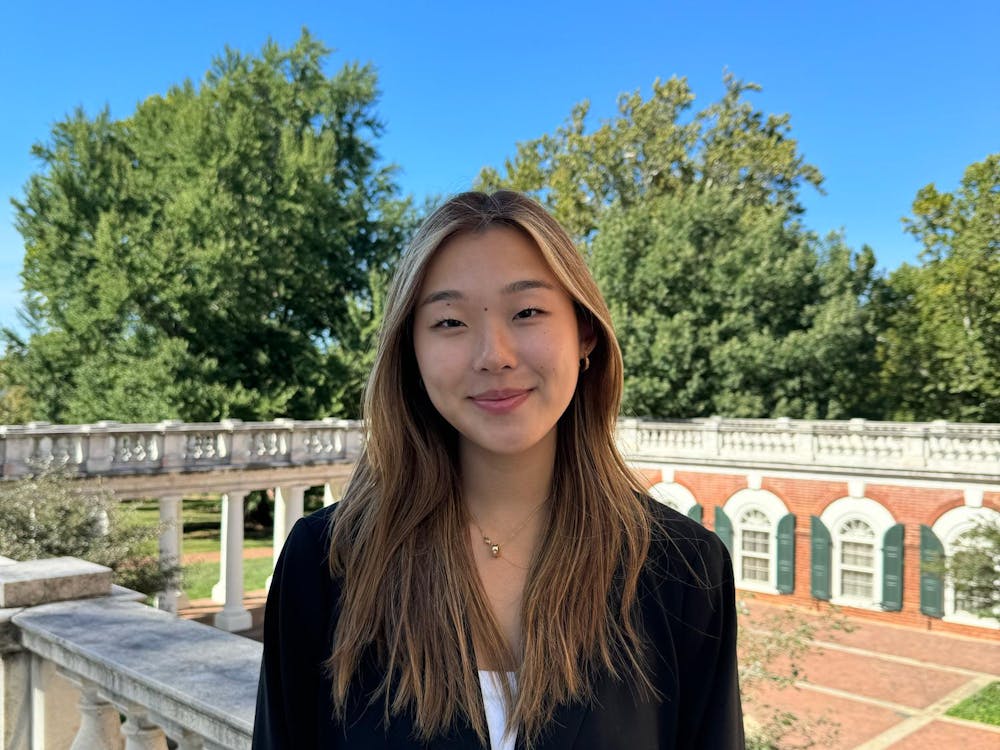

Jason Ono is a Life Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at life@cavalierdaily.com.