In 1979, University President Frank Hereford attempted to censor The Cavalier Daily after it had reported extensively on tense race relations at the University. The publication’s leaders refused to accept the administration’s attempts at oversight. This decision escalated the push for editorial and financial independence that had been developing since 1978 — when the paper first rejected allocated funding from Student Council’s Student Activities Committee. Today, The Cavalier Daily remains independent from the University. This is the story of how it happened.

Tensions rise in the 1970s

The 1970s were a time of great change for the University. Female undergraduate students were only admitted to the College for the first time in 1970. The first African American undergraduate student was admitted in 1955. In fall 1979, the percentage of African American undergraduates doubled from five years prior, going from 3.3 percent in 1973 to 6.3 percent in 1979 — a number that has remained relatively stagnant for the past 40 years — and the black experience at the University was just beginning to be recognized and explored.

Through the 1970s, tensions over race relations were high, as The Cavalier Daily reported on student efforts to expose racism expressed by the University President, faculty and the Board of Visitors.

In 1978, The Cavalier Daily ran an article detailing the Board of Visitors’ statement that they would make a “good faith effort” to desegregate the University, noting that the Board neither approved nor endorsed a proposed plan to increase the number of black students and faculty. Several editorials condemned the unenthusiastic and reluctant commitment on behalf of the University.

“There were a lot of changes, and not everybody appreciated the changes, so I think The Cavalier Daily probably did make some enemies during that period,” said Richard Neel, who served as editor-in-chief from 1979 to 1980.

In the early 1970s, Hereford and over 100 faculty were members of Farmington Country Club, which was known to prohibit both black and Jewish people from entering the club either as guests or members. Students led efforts to force University personnel and Hereford to resign from the club — with one of the loudest voices being Larry Sabato, 1973 to 1974 Student Council President and current director of the University’s Center for Politics.

The Cavalier Daily covered the subsequent large-scale protests and Hereford’s eventual resignation from the club.

“They did not like some of the things we were writing about and editorializing about,” said Mike Vitez, editor-in-chief of The Cavalier Daily from 1978 to 1979. “We had gotten really hard on the president of the University.”

In 1978, Farmington re-entered the forefront of University race relations when the first Dean of African American Affairs William M. Harris was harassed by white students, who yelled slurs and bombarded his home with snowballs in the middle of the night. The attack came after Harris’ comments that had been published in The Cavalier Daily and condemned the use of Farmington’s facility for events by fraternities and sororities as a “deplorable act.”

University’s attempt to censor

It was amidst the publishing of these stories and editorials condemning racist traditions at the University that the Board of Visitors and President Hereford created the Media Board, which was comprised of students, and mandated that The Cavalier Daily recognize its authority. This body had a constitution which enabled it to force student media outlets to publish letters of censure and fire problematic editors.

“Student media organizations may be liable if they publish or broadcast matter which materially and substantially disrupts the educational process at the University of Virginia,” read its constitution.

Vitez saw the creation of the Media Board as an explicit attempt at controlling the content published by The Cavalier Daily.

“It’s a natural collision right?” Vitez said. “Free press and an administration or institution that doesn’t like its message — it was a classic example of the University putting pressure and taking control.”

The Media Board was created in 1976, and the Board of Visitors mandated that The Cavalier Daily recognize it or lose University support in April 1979, just as the newspaper was electing a new Managing Board — a move that Vitez, who was then the outgoing editor-in-chief, called “devious.”

“This all came to a head my first week as editor-in-chief,” Neel said, who had just been elected at the time.

Neel found out about the proposed threat of the Media Board’s authority and the University withdrawing its support from The Cavalier Daily through another student leader, who had been present at the Board of Visitors meeting. At the time, the meetings were closed to the public.

The motivation behind the Board’s increased oversight was ostensibly financial.

“There were legitimate reasons for the University to avoid liability,” Neel said.

The Media Board was officially a measure to exert more control over published content as a way to curb the risk of being liable for inaccurate or inflammatory reporting.

“It was an action taken in abundance of caution because The Cavalier Daily, to my knowledge… we were not sued by anybody,” Neel said.

Vitez believes the Media Board was not created to limit liability but to limit reporting that reflected poorly on the policies and actions of University administrators.

“Back in the day they did not like what we were writing, and that was the genesis of it,” Vitez said.

Neel received a letter April 2, 1979 from Hereford that gave an ultimatum — acknowledge the authority of the Media Board or the University would withdraw its support of the newspaper, including office space, equipment and University-affiliated status. Neel was summoned to Hereford’s office in Pavilion VIII for a meeting the next day to give his response.

“It was a very tense meeting,” Neel said. “I remember the president was sitting in his chair, trying to light his pipe, and his hands were visibly shaking. I wasn't exactly calm myself. I actually brought with me … constitutional law cases and student media articles.”

Neel described how he planned to challenge Hereford’s attempt at exerting authority over the paper.

“I explained to the president that we would not be able to acquiesce to his demands at the time for an answer because we still wanted to consult legal counsel,” Neel said.

The Cavalier Daily rejected the ultimatum and refused to recognize the Media Board’s authority.

“There's a red line because of the First Amendment's guarantee of free press that you can't cross as a regulator,” Neel said.

The outgoing Managing Board of The Cavalier Daily expressed solidarity and frustration in their parting shots published that week.

“Because I know The Cavalier Daily staff — and the rights of the student press, it would appear — far better than they do, I know they cannot and will not succeed in stifling the newspaper,” wrote outgoing Executive Editor Nancy Kenney in her parting shot, entitled “The Cavalier Daily Doesn’t Pretend” published April 3, 1979.

“I am not prepared to allow The Cavalier Daily to operate in defiance of the Board of Visitors,” read a letter from Hereford, evicting The Cavalier Daily from its Newcomb office on April 4.

The Cavalier Daily packed up and moved to rented space at The Daily Progress’ offices in downtown Charlottesville.

“We are still going to put out a paper, and we will continue to do so as long as we can,” Neel said in an article published at the time.

Neel consulted with local attorneys and even traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with lawyers specializing in student media. The general consensus was that because the Media Board had not yet taken action to control the content of The Cavalier Daily, the newspaper was not in good legal standing to go to court since they would not be able to prove intent.

The Cavalier Daily was in a bind — either wait for the Media Board to make an obtrusive decision or take up a losing court case.

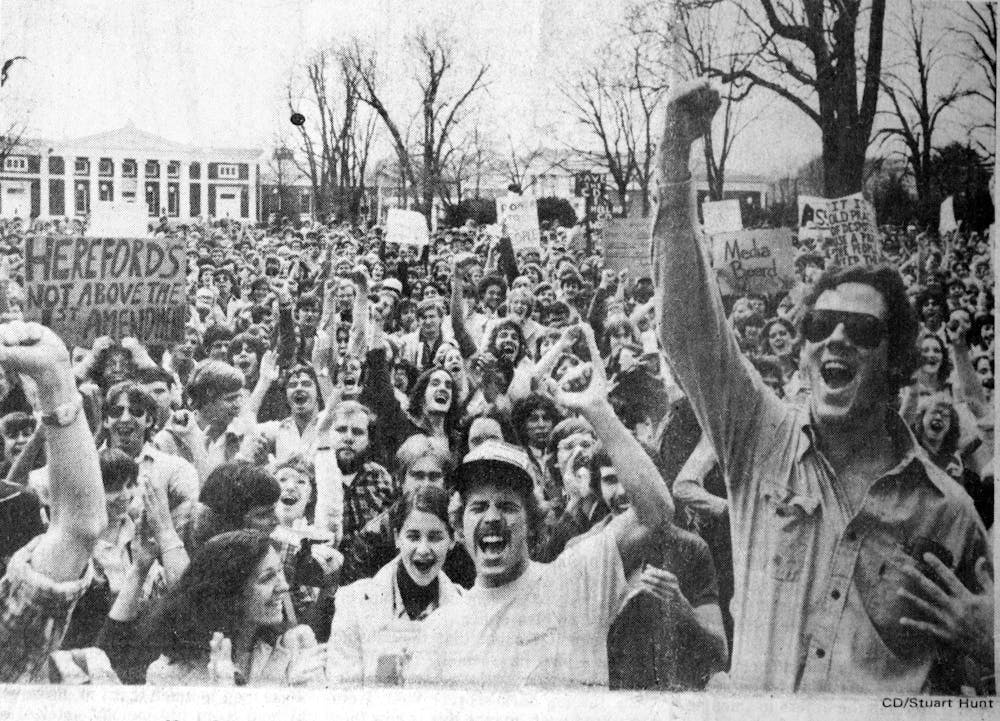

Student Council voted April 3 to condemn Hereford and the Board’s action of evicting The Cavalier Daily. The First-Year Council passed a resolution calling on all students to boycott classes April 5 to hold a rally in support of The Cavalier Daily at noon in front of Hereford’s office.

The student-led resistance culminated April 5, 1979 with 1,500 students protesting and chanting on the Lawn. President Hereford was hung in effigy. Students’ signs read “Free the press” and “What would Mr. Jefferson say?” A banner was hung across the Lawn that read “Behold the fallacy of student self-government.” Hereford was in Atlanta.

Throughout the scandal, The Cavalier Daily continued to print. Editorial headlines read, “Fighting back,” “Fundamental freedoms” and “University ‘deaf’ to students’ voice.” The front cover and the opinion section were emblazoned with headlines about the Media Board conflict for the entire week.

“The University administrators were under tremendous pressure because this became a national news story,” Neel said.

The University’s withdrawal of support from The Cavalier Daily was covered by national media outlets such as The Washington Post.

The shift to independence

The day after the protests, The Cavalier Daily and the University reached a “fair settlement,” according to Neel.

The Cavalier Daily acknowledged the Board of Visitors’ oversight and recognized the Media Board to the extent that it did not intrude upon the paper’s constitutional rights regarding content. University Legal Advisor George G. Grattan IV changed his legal opinion on the Media Board’s constitution — he assured The Cavalier Daily that it could not require them to publish letters of censure.

The University eventually agreed to enter into a “good faith negotiation” with The Cavalier Daily, acknowledging its independence and leasing the paper office space in Newcomb Hall.

“I have also thought that an independent newspaper had merits,” President Hereford said at the time.

Neel said the agreement was an important step in the University’s recognition of the paper’s autonomy.

“That was the first time that the University was willing to entertain the question of independence,” Neel said.

The Media Board had essentially failed and slowly disappeared after the 1979 scandal.

The Cavalier Daily’s struggle with President Hereford and the Media Board set off a trend around the country. Universities resolved to distance themselves from student-run newspapers to decrease liability as opposed to exerting more control.

“Eventually Universities around the country came to realize the same thing,” Neel said. “Their initial thought of more control over student newspapers and radio stations to try to keep a lid on liability … They were better off to create more distance between [themselves] and some of these student groups — especially newspapers.” Student-run newspapers at Syracuse University, University of Florida, University of Kentucky and others became independent in the 1970s.

When universities financially distance themselves from student media, as explained by Neel, they make it harder for people filing suit to access the “deep pockets” of the University.

“A very important first step toward independence had already been taken … It was in the spring of ‘78 that The Cavalier Daily first declined an allocation of Student Activities Committee money … and became essentially financially independent,” Neel said.

Vitez referred to The Cavalier Daily’s office in Newcomb Hall, saying it was the University’s only remaining financial contribution to the newspaper.

“What the University gave us was free space,” Vitez said. “Otherwise we were entirely self-reliant.”

However, the Managing Board of The Cavalier Daily was blindsided when amidst the Media Board scandal, the Student Activities Committee decided to allocate the newly available funds to a second newspaper — the UVA Daily. The UVA Daily, which later became the UVA Journal, was started by a single student and was “ran off on a photocopier.” This paper would continue to publish well into the 1990s and staff “very talented” writers according to Neel.

The Cavalier Daily was unable to begin paying rent for Newcomb Hall office space until the UVA Journal folded in 1998, which eliminated the economic competition for readers and advertisers.

“The University community was not large enough to support two financially viable daily newspapers,” Neel said. “The UVA Journal did delay the independence of The Cavalier Daily.”

Vitez noted that The Cavalier Daily’s fight for its constitutional rights was a deeply formative experience, citing the dedication of the paper’s staff.

“That is where I learned all about commitment and passion and fairness and fighting for a cause and integrity,” Vitez said. “The people I worked with were amazing and shaped me, shaped me completely. It was the most impactful experience I got from my four years.”