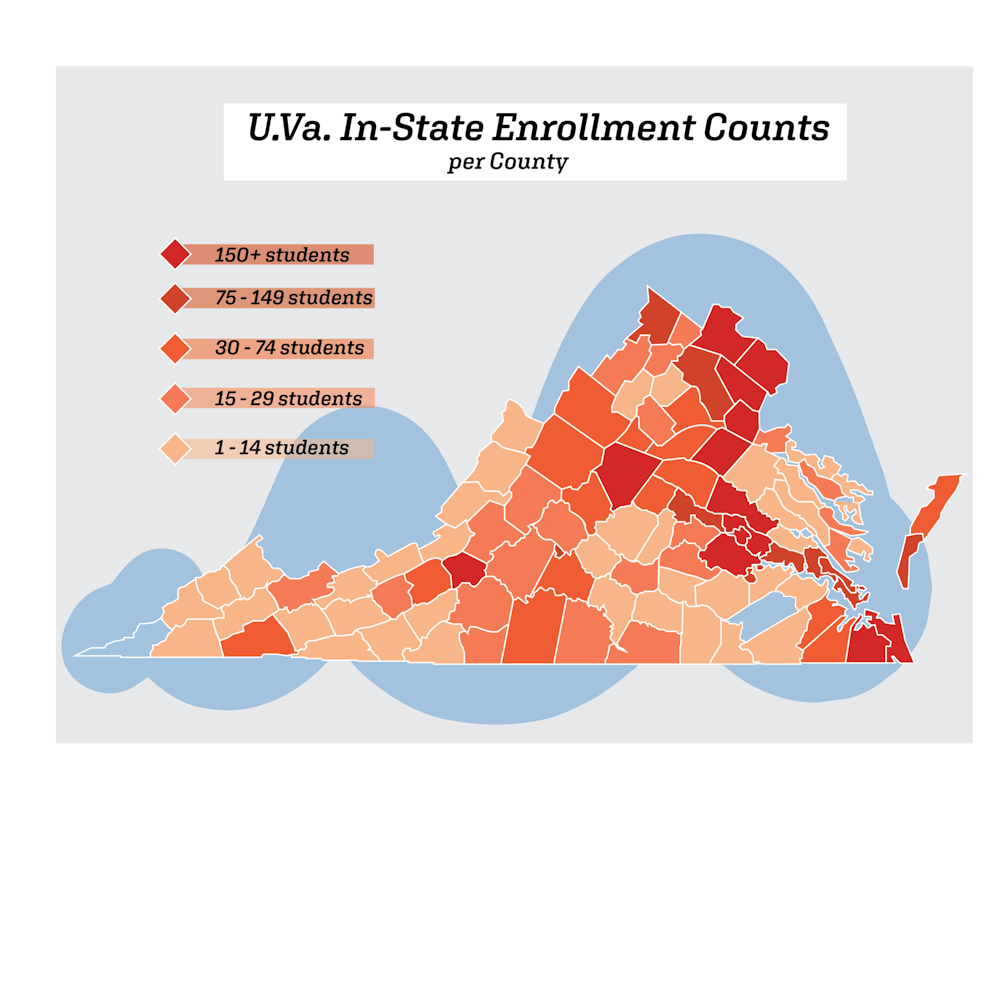

Though the University reserves two-thirds of spots each year for in-state students, there is a sizeable disparity between the regions to which these spots are allocated. While hundreds of students from the counties outside of Washington, D.C. enroll each year, Virginia’s more rural counties rarely enroll more than 10 students each within the entire undergraduate community in a given year.

According to an enrollment map of the University, there are currently 3,481 students from Fairfax County and 1,148 students from Loudoun County, 496 students from Arlington County, 255 students from Alexandria County and 609 students from Prince William County — all densely populated areas in Northern Virginia. In contrast, there are eight students from Alleghany County, two students from Craig County, seven students from Bath County and two students from Highland County — all more rural areas further west.

Third-year College student Ryan Deane grew up in Greene County, about half an hour north of Charlottesville, where around 50 other University students live. Though her home is not too far from Grounds, the area is less affluent and developed than Charlottesville and communities in Northern Virginia — there was not a Walmart in Greene County until Deane was 12-years-old.

“I felt like I didn’t belong [at the University], first of all, because growing up I was surrounded by other middle class and low-income students,” Deane said. “When I got to U.Va., there was this extreme feeling of elitism and money, being poor isn’t something that’s really talked about. Being from a rural area, especially when it seems everyone from Virginia is either from Northern Virginia or Virginia Beach, so they know what it’s like to grow up in a more developed area with better education systems.”

Deane’s experience is not unique to Greene County. In many more underdeveloped and rural counties, students are left with much less guidance in the college process and unclear expectations of what to expect from the college transition, which Deane claims she was not provided by her high school nor the University during her summer before starting college.

Austin Widner, a 2019 graduate of the University, spent his entire college career striving to help students from communities like his home in Craig County. Only 4 out of the 67 students in Widner’s graduating class pursued higher education. Like many of his classmates, he had to travel to the local McDonald’s in order to access Wi-Fi and submit college applications.

As a co-founder of Friends of Appalachia — a CIO designed to create a mentoring network for prospective and current students from Appalachia transition to the University — Widner aimed to show students from rural communities that they have a place at the University by providing the guidance and support they previously lacked.

“I am very careful with the way I speak of Appalachia — my every effort is to empower the area and the people of it,” Widner said. “Friends of Appalachia is not a solution, but a conduit for resources into and out of the area. The people, kids through the elders, are all apt and ready, but are lacking the resources necessary to excel … How could the state university not service its entire state thoroughly?”

Widner found his way to the University through the Rainey Scholars program, which offers free summer classes for students the summer before entering their first year and a financial aid package that he reports added up to more than his family made in a year. The other student from Widner’s hometown, who he met through the scholars program, lasted all of six hours after move-in, overwhelmed and ill-equipped for the daunting transition to college.

“The topic of race or SES never came up [in the scholars program], and many of my best friends in my first year were the Rainey Scholars that I shared my summer with,” Widner said. “There were so many parallels between our experiences despite from being from low SES areas all over the nation — we were able to often share an unspoken bond that transcended whatever challenge we were facing in our time at U.Va.”

Even after graduating and spending four years in Charlottesville, Widner says he has stayed true to his roots. Transitioning to the University meant adjusting to a foreign culture, including no longer growing what he ate himself and figuring out how to use the buses on Grounds — yet to this day Widner has never ordered from a Starbucks.

“Quite frankly, the important takeaway here is that one never truly transitions,” Widner said. “As hard as I fought it my first year, I could hardly cut myself from the roots that helped me grow, and I believe that there is so much beauty and value in the luggage that students from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

In light of Widner’s graduation in May, third-year Engineering student Benjamin Johnson is the current president of FOA. According to Johson, coming from Botetourt County in western Virginia, which is largely farmland and home to just 25 students at the University, Charlottesville may as well have been a large city. His transition to the University was marked by a lack of resources and feeling there was no guidance, barring FOA, for students from rural areas.

“I think that, where the ball gets dropped, is that students from rural areas may not get the counseling that they need to understand how to use University resources to benefit themselves and to feel like they fit in,” Johnson said. “And so I think that, where the University can improve and capitalize on is making sure that students from those geographic areas are really reached through their advisors, or through different life counseling or advising groups to show them.”

According to Wes Hester, director of media relations and deputy University spokesperson, the University recruits in rural areas by visiting high schools, hosting informational events and sending current University students who have experienced the college process and the process of paying for college in hopes of attracting students from rural areas.

“Supporting students from rural areas is irrelevant if they are not being recruited, and in turn, not accepting offers that they receive,” Widner said. “Once rural students are here, they need communities that enable and empower them, and make them aware of their own identities while also showing them how their experiences relate to others.”