The Mapping Cville Project has obtained over 300,000 pages of property records from the City and the County, and volunteers have begun reviewing City deeds for racially discriminatory language to help provide historical context for Charlottesville’s current housing landscape.

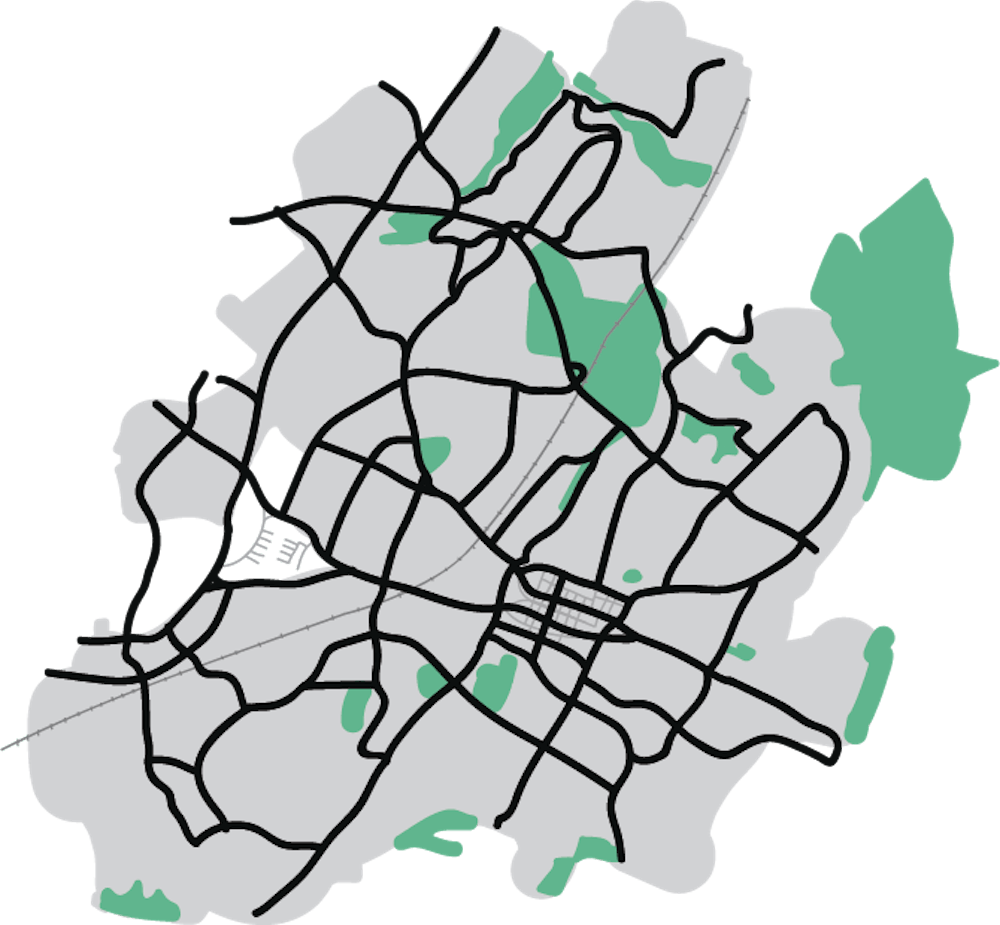

The project aims to develop an interactive digital map of past and present inequities in Charlottesville, and its first layer will show housing discrimination origins by plotting every deed in the City that contains a racially restrictive covenant — clauses within property deeds that restricted the sale of properties to only white residents and often explicitly prohibited sales to African-Americans.

During an event last Saturday for the project’s public release of its next phase, volunteers learned how to assist in the project’s data compilation by identifying and recording these racial covenants in an online database.

Jordy Yager, local journalist and digital humanities fellow at the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center, started the Mapping Cville Project thanks to a $50,000 grant from the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation he received in the summer of 2018.

The project will culminate in an interactive map with both an online iteration and a physical exhibit at the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center.

While providing background information and describing the impetus for the project during the Nov. 23 event, Yager cited an “opportunity atlas” created with U.S. census data under the direction of Raj Chetty, a Harvard-based economist.

“[Chetty] started mapping the census data to show in detail how where you live is the number one determinant of what happens to you in life,” Yager said.

The atlas ranked Charlottesville as 2,700th out of 2,800 neighborhoods for the ability of residents who are born into poverty to eventually get out of poverty.

Yager said he began exploring the origins of neighborhoods after delving into research and hearing anecdotal experiences that indicated that stark disparities in areas such as income, education and healthcare usually fall along racial lines in Charlottesville.

“All these neighborhoods that we consider legacy neighborhoods today have not always been here,” Yager said. “They had an origin point — they were created at one point. And so if where we live is the number one determining factor in terms of what happens to us, why do we live where we live?”

The records obtained by the Mapping Cville Project span from 1888 to 1968, when the Fair Housing Act was passed. Although the Fair Housing Act made racial covenants illegal, zoning laws effectively yielded similar effects of segregation. Land use regulations and building code requirements excluded lower-income residents from certain areas, creating concentrated communities of white and wealthy families.

“In ‘68, the Fair Housing Act says [racial covenants are] no longer constitutional, but what happens then with our zoning laws?” Yager said. “Does this just get a different shade — a different kind of language — that gets applied to it, but the same outcomes?”

City Council and the City’s Planning Commission hope to address zoning issues in its new Comprehensive Plan that began development in fall 2018.

“[City Council is] very much aware and excited about this [project] and incorporating this into their work,” Yager said. “And so how that’s done is really not up to me, but I think arming decisionmakers with the most data, the most reliable historic information is something I’m very passionate about as a journalist and as a researcher.”

Although Yager and his team did explore the possibility of coding a program to mine info from digitized property records, the language of the deeds is unstandardized and highly variable, with records before 1903 written in cursive.

Therefore, according to Yager, human interaction with the documents is necessary to accurately glean the information needed to create the digital map, and the project has turned to the public for help. The project is truly a community effort, with contributions from members of both the larger Charlottesville community and the University community.

Contributors from the University community include Barbara Brown Wilson, assistant professor of Urban and Environmental Planning, who helped develop the project’s methodology, as well as students, who helped to digitize pages of the property records in a class taught by African-American Studies Assoc. Prof. Andrew Kahrl in fall 2018.

This phase of the project to plot racial covenants in the city as the base of the digital map will likely be completed by the end of the spring, and subsequent layers will map racial covenants in the county and then infrastructure.

“There’s no end to what we can layer on top of it in terms of looking at contemporary data, historical data,” Yager said.

Those who would like to contribute to the project can access a tutorial and learn how to contribute on the Mapping Cville project website.