Liberal politicos have assumed for years that once we become a majority-minority country, or a nation in which less than half the population identifies as white, the Republican Party will fade into oblivion. Many conservatives share the same prediction. A year after Romney’s defeat in the 2012 election, the Republican National Committee released its Growth and Opportunity Project, a post-mortem scramble to fix the Republican Party’s messaging problem and diversify its voting base. But what both parties ignore are the wealth of historical, cultural and geographic considerations that may undermine this prophecy.

It goes without saying that conservative opposition to the civil rights agenda in the 1960s has permanently hindered the Republican Party’s appeal to African Americans. In the decades since, the party has made virtually no progress with black voters, 84 percent of whom currently identify with the Democratic Party. Though African Americans are unlikely to make the ideological flip anytime soon, historical trends indicate that the same may not be true for other minorities, especially Hispanics.

Interracial marriage and the shedding of ethnic identity will play a large role in disrupting many other racial groups’ electoral allegiance to the Democratic Party in the long term. Twentieth century America welcomed a flood of Italian, Irish, Polish and Eastern European immigrants whose ethnic heritage rendered them subject to discrimination from assimilated whites. As their accents and cultural traditions faded with time, however, they became subsumed into the white mainstream and fled to the Democratic Party in herds. The U.S. will likely witness a similar trend with Latino voters in the next decade, as cultural links to Hispanic heritage vary widely across immigrant generations.

Whereas first generation Hispanic immigrants are much more likely to speak Spanish, have Hispanic friends, feel connected to their country of origin and live in Hispanic neighborhoods, a recent Pew Research poll shows us that these trends are much less pervasive among higher generation Latinos. Growing rates of interracial marriage, the increasingly blurred line between racial and ethnic identification and fading Hispanic identity will also cause many mixed-race Americans to begin identifying as white.

Hispanics, who are predicted to become the largest minority voting bloc in 2020, present an interesting case study in voting behavior as they are not as ideologically monolithic as liberals tend to think. A dominant assumption among the left is that the Republican Party must relax immigration restrictions if it is to appeal to minorities. But many Hispanics who immigrated legally support more restrictive immigrations policies on the basis of fairness. Foreign policy also presents a dilemma for Hispanics. While Cuban-Americans — incensed by their home country’s communist history — have consistently voted Republican, Venezuelan support for the Trump administration’s opposition campaign against Nicolas Maduro suggests that this demographic may follow suit. Hispanics are also much more socially conservative than liberals tend to think, as evidenced by their fairly low support for abortion compared to other racial minorites. According to exit polls, Trump won over a quarter of the Hispanic vote in 2016, and even reached a thirty percent approval rating among Hispanics in 2018. Despite these trends, however, the “demography is destiny” hypothesis prevails.

The dominant assumption is that the country’s minority-majority future means that ethnic minorities — who overwhelmingly lean liberal — will inevitably outnumber the Republican Party’s disproportionately white voting base. But that proposition depends on immigration rates remaining constant. Even though white voters are predicted to constitute a minority of the population by 2050, it is still unclear how much Republican support will be lost.

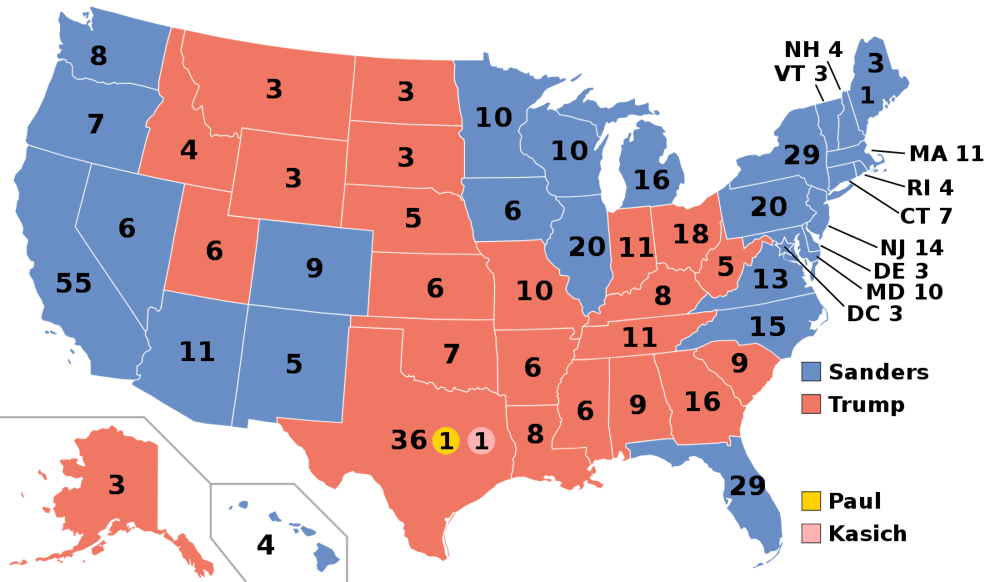

This theory also presumes that demographic diversity is widely dispersed, which is untrue. Immigrants disproportionately flock to the coasts and metropolitan areas which already lean liberal. 45 percent of immigrants live in just three states — New York, California and Texas. Unless immigrants start moving to the Midwest or the Deep South — beyond just the Lone Star State — the Electoral College will continue to balance out sheer immigration increases.

As center-left think tank Third Way has documented, the shocking number of young voters who identify as independents also stunts the left’s demographic calculus. Among Asian millennials in 2016, 43 percent identified as independent/don’t know, 16 percent as Republican and 41 percent as Democrat. Among Latino millennials, those numbers are 37, 16 and 47 percent respectively. While the disparity between Republican and Democratic affiliation is admittedly stark, the high proportion of independents means that not all young minority voters are unabashedly progressive.

Historical trends regarding voting behavior show us that electoral majorities are far from permanent. As Ramesh Ponnuru explains, “In 1925, it would have been natural to assume that the South would stay Democratic, blacks would stay Republican, and the working class was moving toward the GOP” — but none of these predictions withstood the test of time. Political scholars should stop putting minority voters in a box and realize that there’s more to the equation than demography alone.

Audrey Fahlberg is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.