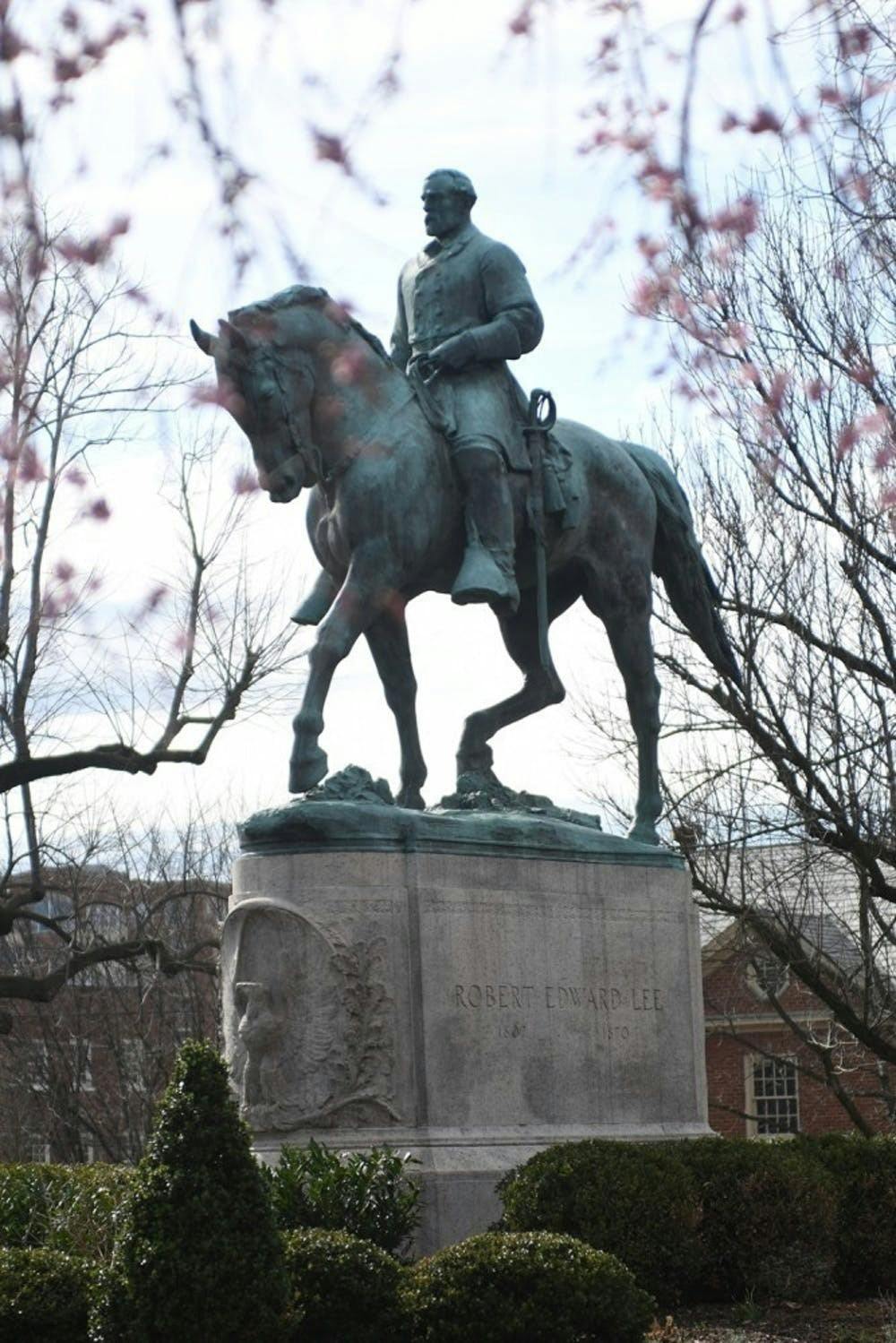

It has been over three years since the efforts to take down the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville began. Perhaps no recap can do justice to what’s happened since. There was a city council vote to remove the statue and which was subsequently blocked by a Virginia judge. The white-supremacist rally in August 2017, which was organized in response to the effort to take the statue down, forever made the racism deeply embedded in American society unignorable. Now the struggle to alter the landscape of Confederate statues is reaching a climax as a statewide campaign known as Monumental Justice seeks to pass legislation allowing localities to remove them.

At the center of the inability to remove the statues is a law on “war memorials.” The fact that these memorials commemorate a losing slave-holders’ rebellion apparently holds little merit, which has led to the need for a fix from the General Assembly. Fortunately some legislation to amend the Virginia code to allow cities to remove statues will be introduced in the House of Delegates by Del. Sally Hudson, D-Charlottesville and in the Senate by Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Bath, in the upcoming legislative session. This is a welcome development, but it requires a movement to back it up.

Despite Virginia Democrats now having a trifecta at the state level, they appear far more cowardly than one would hope. Former Republican voter and current Governor Ralph Northam repaid the myriad of labor unions that got him and his majority elected with an attempt to shut down any talk of repealing anti-union laws in Virginia. I’ve written elsewhere about why this is both a politically moronic move and hampers the ability of working-class Virginians to improve their lives. Unfortunately, the struggle to finally let municipalities remove Confederate statues may face a similar fate.

Unite the Right, lawsuits and civic groups have made the backlash against correcting the landscape of Charlottesville a brutal affair. They’ve fought to uphold the ideology of white supremacy and its creations in the form of Confederate statues. It will thus require the full force of residents of all counties and municipalities in the Commonwealth to petition their representatives to allow the removal of these symbols of white supremacy once and for all.

This struggle over our history, one that is so often won by the wealthy and powerful over the working class. In 1935, W. E. B. Du Bois charted a black working-class history of Reconstruction in “Black Reconstruction in America.” Not only is all of it is worth reading, but he also identifies the very dynamics we see at play in the struggle for monument justice today.

Du Bois writes, “Of all historic facts there can be none clearer than that for four long and fearful years the South fought to perpetuate human slavery … Yet one monument in North Carolina achieves the impossible by recording of Confederate soldiers: ‘They died fighting for liberty!’” How the losers of the Civil War could then be memorialized as the great defenders of liberty is a question that has rooted much of the fight over Confederate statues. Perhaps it becomes clearer when one realizes that the families that held slaves quickly regained their wealth, influence and power to rewrite history after abolition.

One lesson Du Bois attempts to convey in “Black Reconstruction” is that the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction are a struggle. The black workers who revolted in slavery during the war and then struggles for control of their towns, took part in a racialized class struggle that continues today. The fight for monuments that reflect our values is coupled with our fight for material change to our lives. We are closer than we’ve ever been to reshaping the racial landscape of Virginia — now’s the time for a final push. Perhaps a rally planned for Jan. 8 at the state Capitol will finally deliver the long-awaited victory for Monumental Justice.

Jacob Wartel is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.