After rounds of clinical trials, researchers with the University Center for Diabetes Technology have created an “artificial pancreas” for patients with Type I diabetes. Until this technology, patients with Type I diabetes had to serve as ‘translators’ between two medical devices — insulin pumps and glucose monitors. But just recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the new device, which will allow insulin pumps and glucose monitors to ‘talk’ to one another — turning two devices into one and creating a streamlined approach to diabetes management.

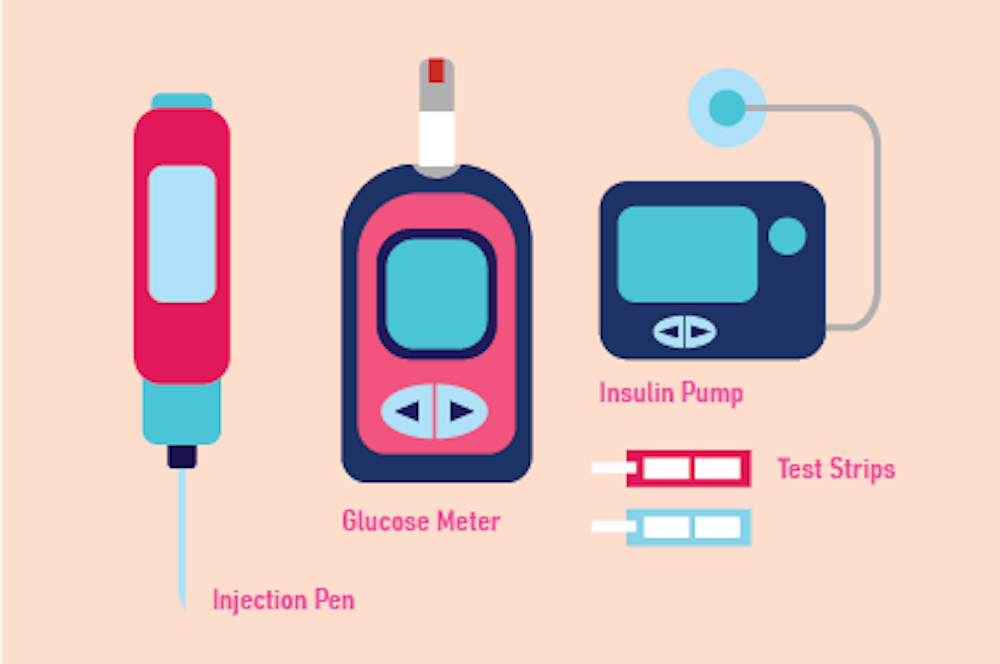

Sue Brown — University medical professor and endocrinologist — describes that before each meal, diabetes patients must monitor their glucose levels using a glucose monitor and count the carbohydrates in their meal to determine how much insulin to administer through an insulin pump. Even activities such as playing sports and sleeping at night require the close monitoring of glucose levels and potentially the administering of insulin, Brown explained.

She further stated that this continuous process of monitoring glucose levels, evaluating meals and administering insulin is not a simple one and that diabetes patients need an easier process. But before then, technology must fill an important gap in diabetes management.

“We've had insulin pumps for a long time and monitors, but they never adequately talked to one another,” Brown said.

Through a decade-long clinical trial, researchers at the University’s Center for Diabetes Technology have successfully developed an artificial pancreas system that allows for seamless communication between glucose-monitoring technology and insulin-injecting technology. This single device analyzes the body’s glucose levels to release the required insulin every five minutes. Although the accuracy of the device improves as patients input the numbers of grams of carbohydrates they eat, Brown stated that inputting that number is not absolutely necessary.

This system, which synchronizes glucose monitoring and insulin administration, has one benefit that stands out among the rest — obtaining healthy overnight blood sugar levels.

“A big worry for people with Type I diabetes is that blood sugar will be low in the middle of the night, and [patients] won't know [that] when they are asleep,” Brown said. “Our clinical trial really shows that [the artificial pancreas] is working overnight to get a consistent blood sugar for people in the morning, and 90 percent or more of the time, blood sugar is consistent in the morning hours.”

The FDA also recognizes the effectiveness of the device, as the large-scale, decade-long clinical trial officially received FDA approval less than two months ago.

While the Center for Diabetes Technology is largely responsible for getting FDA approval of the device, it is not an insulin pump or glucose monitor manufacturer, explained Marc Breton, associate professor of research and technology developer with the artificial pancreas team. Instead, its focus has been on designing the algorithm to link the two.

“The center at U.Va. is not a pump or sensor manufacturer, so we rely on very close relationships with manufacturing companies — Dexcom and Tandem,” Breton said. “The mechanism of pump is not our specialty. We created the brain of the system, [and] our role was linking the two.”

Boris Kovatchev — founding director of the Center for Diabetes Technology and principal investigator for the artificial pancreas team — added that creating the technology for the “brain” was far from straightforward because nothing like the algorithm had ever been designed before — especially not something so interdisciplinary.

Building the algorithm required a team of multi-disciplined doctors and mathematicians, as collaboration was key to a successful study. As a result, the team’s mathematicians had to understand the medical information while the doctors had to understand the algorithm used in the device, explained Kovatchev.

Although FDA approval has been granted, the artificial pancreas team still anticipates several steps occupying them in the coming months or maybe years.

For Breton and the rest of the team, the next steps are to complete the validity of the system. Currently, the system is only approved for use in 14-year-old patients, but the team is working to gain approval for use in six-year-olds — which should be completed in the next two weeks. After that, they hope to gain approval for use in two-year-olds as well.

Breton also added that the team hopes for the development of a more “sit and forget” mechanism — one where patients will no longer have to calculate and input carbohydrates into the device at all.

In addition, Brown hopes to study and then incorporate information on blood sugar levels during exercise as well as the menstrual cycle into the artificial pancreas’s technology.

Regardless, Brown hopes that this new technology can simplify the lives of Type I diabetics by reducing glucose monitoring, carbohydrate counting and insulin injections.