We first met Humbert Humbert in 1955.

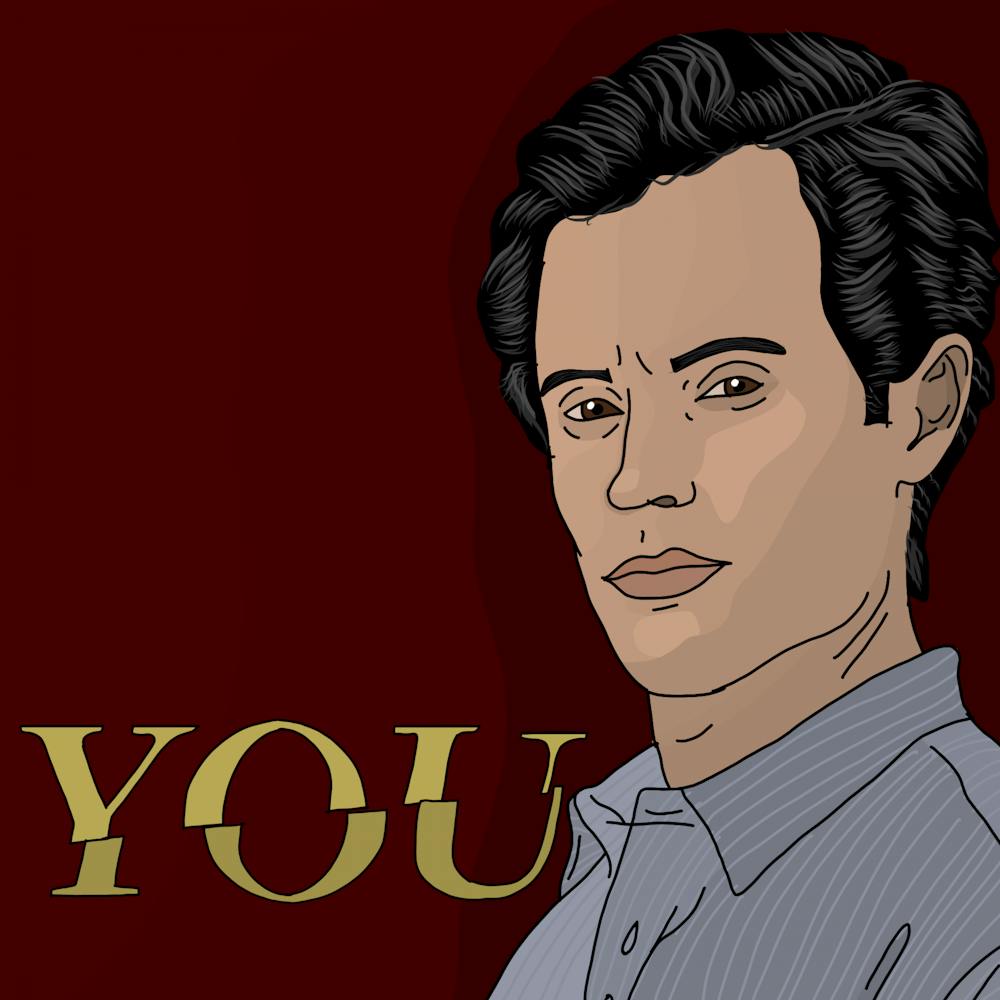

The erudite, pedophiliac narrator occupied the pages of “Lolita,” the famed yet controversial novel by Russian author Vladimir Nabokov. Today, we meet him again as the cunning anti-hero Joe Goldberg of the Netflix original series “You.” Goldberg is Humbert Humbert — a stalking, unreliable narrator with a savior complex — revamped for a modern American audience.

On the very first page of “Lolita,” Humbert establishes his readers as the “ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” expecting them not only to examine but to judge “exhibit one” — the story he is about to present. He takes time to describe his first love Annabel, with her “brown bobbed hair” and “thin arms,” or later Lolita’s “honey-hued shoulders'' and “silky supple bare back.” Similarly, Goldberg also invites his audience to observe — from the moment Guinevere Beck stumbles into his bookshop in season one, to the time Goldberg spots Love inspecting an heirloom tomato at Anavrin in season two. He guides viewers in visually deconstructing these women with sociopathic accuity — “Who are you?” he asks rhetorically. Within minutes it is known that Beck is a student. She has a wide blouse, a sign that she does not want to be “ogled” but has jangly bracelets that ask for attention, he observes. Love has a shirt that is “faded but fresh,” and she likes to “take care of things.” Unlike Humbert Humbert, Goldberg has the advantage of having another set of eyes — the internet — which he uses to unearth excessive information about everyone. These men are flâneurs — professional observers in the literary world.

Their identity as intellectual, white and financially well-off males allows them the privilege to stroll around virtually unnoticed and be spectators, even voyeurs, without the scrutiny that often comes with more marginalized identities. Humbert is able to travel across America while sexually involved with a minor with little attention from bystanders or witnesses. Goldberg is able to stalk his targets or don his baseball hat and immediately become practically invisible, allowing him to commit murder and walk around with bags of human remains without any repercussions. The audience is given a glimpse into this flaneurism as Goldberg and Humbert act as the audience’s eyes and ears, through which they experience the characters’ lives. However, can their observations truly be trusted? What makes these characters so unreliable is that their narration often points inward rather than outward, causing their perspective to be clouded with self-delusion. This self-delusion is rooted in their beliefs that they are not doing anything wrong because their wrongdoing is justified. Like Humbert said, “You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style.” The convicted are eloquently presenting their case, and they are not pleading guilty.

Additionally, Goldberg and Humbert both justify the way they take advantage of women with their intrinsic need to save people. Humbert convinces himself and manipulates Lolita into believing that she is safer with him. He terrorizes her by telling her what would happen if she went to the police — he would go to jail and she would become “the ward of the Department of Public Welfare” and that it would be “a little bleak.” He weaves a sick story — assuring her that he is saving her from the evils of the outside world. He emphasizes the fact that she had no other option, that “she had absolutely nowhere else to go.” Goldberg adopts a similar mentality in “You.” He decides to play God and kill the people who stand in the way between him and his love interests. He believes that it is his job to protect these women. “Sometimes, we do bad things for the people we love. It doesn’t mean it’s right, it means love is more important,” Goldberg says. He and Humbert may think they are self-sacrificing Christ figures, but in reality they are the very predators Lolita, Beck and Love should be protected from.

By offering a skewed perspective and justifying their repulsive deeds, Goldberg and Humbert still manage to draw out sympathy from their audiences. How? Two characters with such questionable morals cannot possibly be considered protagonists or heroes, yet Humbert seduces the audience with lyrical prose and deliberately leaves out graphic sexual details to distract from what is really happening to Lolita, even claiming that “it was she who seduced me.” Goldberg focuses so much on his own quest for love that when he finally attains it, the audience cheers and seems to forget how many lives it cost. The reactions to these anti-heroes seem to mirror society’s reactions to real-life predators — not enough condemnation for their actions and little justice for victims.

In the end, art imitates life — and even 65 years later Joe Goldberg continues the legacy of Humbert Humbert.