In the past month, one number has circled around news feeds and public spaces over and over again — six. Around the world, citizens are being told to stay 6 feet apart, quickly becoming all too familiar with the practice of social distancing. Many aspects of everyday life have turned virtual, from education and work to ordering dinner and working out. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines social distancing as simply keeping space between yourself and others outside of home. The conditions to do this include remaining 6 feet apart, not gathering in groups and staying away from crowded places and mass gatherings.

For Costi Sifri, director of hospital epidemiology in the University Health System, and Physics Prof. Lou Bloomfield, the importance of and science behind social distancing go hand in hand. By separating the population, vulnerable populations can be protected, and exponential growth can turn into exponential decay.

“The mechanism for the infection process is textbook for exponential growth,” Bloomfield said. “Compound interest is an example of a system that has exponential growth. Your money keeps increasing and the rate at which it increases, increases … Here is an example of exponential growth of something we don't want.”

In support of the idea that social distancing rapidly slows down the spread of COVID-19, Sifri explained that the need for social distancing stems from the absence of physical symptoms in many virus carriers.

Sifri, the University Health System’s lead public health officer, was tasked with preparing the University and medical center for COVID-19 infection, in addition to acting as the liaison for the Virginia Health Department and other hospitals in the area. According to Sifri, the main issue is the difficulty to recognize mild COVID-19 symptoms.

“There's really no specific clinical signs and symptoms that reliably discriminate COVID-19 infection compared to other viral infections,” Sifri said. “When [coronavirus] first arose during the cold and flu season, social distancing and other non-pharmaceutical intervention measures became of paramount importance because that's one of the only tools that we really have to combat this.”

Though the degree to which social distancing is being employed is more extreme than has ever been seen before, Sifri says that its framework has stemmed from the last 10 to 20 years of public health research and stemmed from the concern over a potential pandemic influenza. In 2009 and 2010, the H1N1 pandemic resulted in some school closures, though the efforts pale in comparison to what is occurring now.

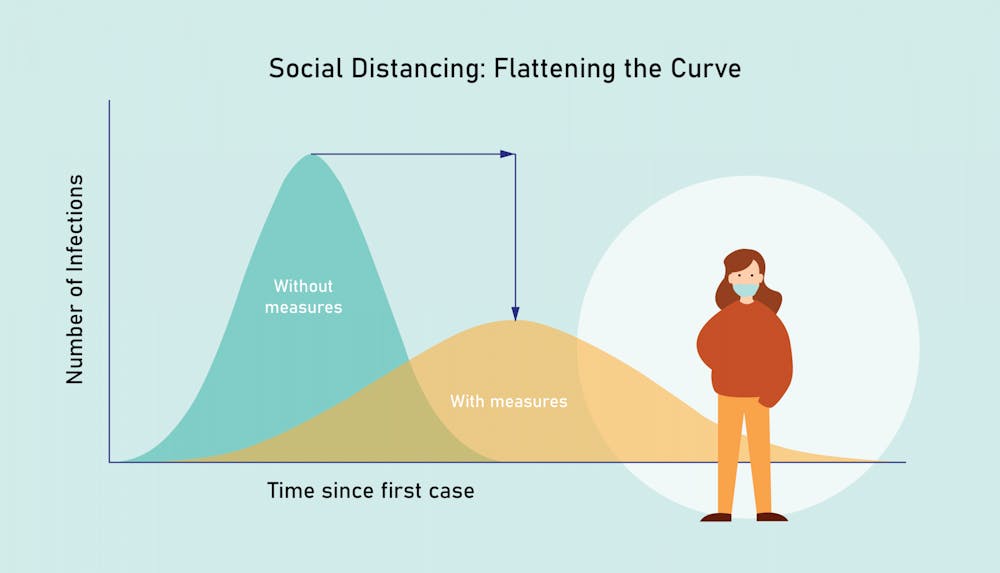

When faced with the concern that people are not socially distancing to the degree that they should — perhaps thinking their actions are insignificant — Bloomfield stresses that every effort does matter, and everyone needs to contribute to flattening the curve.

“We're all part of this big statistical experiment in which tiny little morsels of influence add up,” Bloomfield said. “It’s worth trying [to save] every last one of those … The life you save could be your own or someone you care about.”

Bloomfield noted that many times the people that one is likely to infect or be infected by are ones they know and love and that people are realizing too late that they messed up, apologizing for it after the fact.

Third-year College student Natalie Groder, who remains in Charlottesville, says she has seen misinterpretations of social distancing guidelines and failures to adhere to them by University students, expressing disappointment that those actions could extend the situation much longer than needed.

“We should be taking personal responsibility to help in whatever way we can,” Groder said. “We're only being asked to stay home and to limit our interaction … It is hard in terms of feeling isolated, but if it will save people's lives, then it's definitely important to do.”

Though Sifri acknowledges that more can always be done, he is impressed by the amount of social distancing which has occurred in such a short period around the nation.

He also believes it is important to recognize the vulnerable groups who are not able to socially distance. These groups not only include healthcare workers and first responders, but also people living in congregate settings like long-term care facilities, jails and homeless shelters.

According to Sifri, these populations amplify healthcare inequalities that already exist and that by combining social distancing with efforts such as early diagnosis and contact tracing, people can prevent infection within those populations that cannot receive the benefits of social distancing.

“This is a stealth virus,” Bloomfield said. “Nature designed this one well to run rampant in the whole world's population. The only way to control it at present is to take away its ability to move from person to person by keeping people apart.”

As many in the United States continue to social distance, President Donald Trump’s “30 Days to Slow the Spread” campaign and Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s stay at home mandate are geared to lessen the effects that Costi and Bloomfield have stressed.