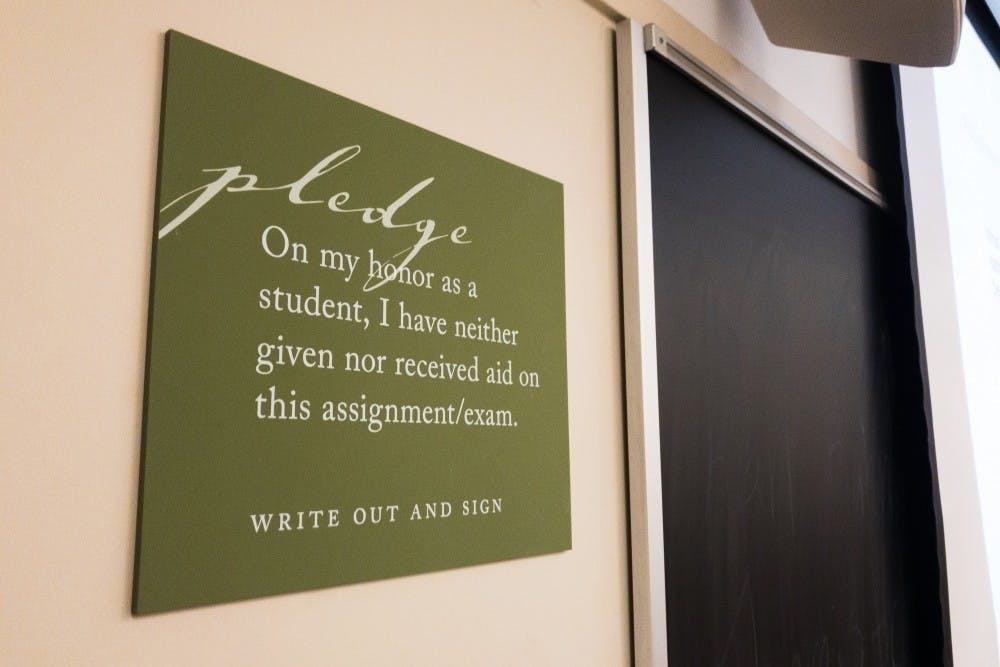

In the past few months, debates about the honor system have echoed across the University community. From rent payments to Title IX-related offenses, the honor system has continued to change its role and scope in University life. However, many of these conversations fail to discuss the core problem with the honor system — single sanction.

Single sanction is a fundamentally morally corrupt policy that is flawed in both its underlying philosophy and tangible application. Much has been done to reveal the vastly inequitable ways in which single sanction affects U.Va. students — for example, that international students and students of color are disproportionately likely to be accused of honor violations. However, I will focus on the flawed moral logic of single sanction and how it operates on a fundamentally narrow, punitive vision of justice.

At its core, single sanction is a zero-tolerance policy. It serves as a mandatory minimum that paints all offenders as equally repulsive and therefore equally deserving of the most severe punishment an educational institution can issue — expulsion. This startling lack of scope is single sanction’s greatest flaw. Every offender — no matter the context, no matter the intent — is painted with the same broad strokes. Liar. Cheater. Thief. However, when we categorize our classmates as either the honorable “good” and dishonorable “bad,” we make a terrible mistake. Not only are all human beings capable of both goodness and badness, but this form of black and white thinking also assumes that all “bad” actions are equally bad. Stealing a pack of gum and stealing a car are staggeringly different crimes, but to the Honor Committee, individuals who commit these actions are both “thieves.” While offenses must reach an arbitrary level of “significant” to be adjudicated by the Committee, the fact that the options left to the Committee in the gum-stealing case are to either expel the student or do nothing is itself troubling. Single sanction cannot justify itself without erasing the complexity of human behavior and turning to essentialism. However, despite insistence otherwise, a person who takes an extra ten minutes on a take home exam is no more essentially a cheater than someone facing a University Judiciary Committee sanction for property destruction is essentially an arsonist.

Further, considering there is a multi-sanction system for other student offenses, what makes honor offenses different? For the University to separate such offenses from other breaches of conduct — to reserve them for automatic and unequivocal expulsion — there must be something inherently worse about them. However, this simply isn’t the case. Honor offenses certainly don’t tangibly harm others more than UJC offenses. Physical assault is a UJC offense, and the deep physical and emotional trauma caused by physical or sexual assault can easily be more impactful than that inflicted on a victim of property theft or cheating. If tangible harm was the deciding factor, every individual found responsible for a Title IX offense or a physical assault UJC offense would be swiftly expelled. Statistics on sanctions from Title IX alone reveal that this is simply not the case — for example, during the 2018-2019 school year, only 11 percent of individuals found responsible of a Title IX violation were expelled.

Why then, do we find honor charges to be so different, when they clearly are not among the most harmful things a student can do? The clearest answer is that honor offenses can harm the University’s reputation, while also offering the University a positive reputational boost for severely punishing students who commit them. While incidents of sexual violence can harm a Unviersity’s reputation, harshly punishing — and thus inadevertnatly publicizing — them can expose schools to being perceived as “unsafe.” However, for the kinds of academic dishonesty that the Committee primarily handles, the single sanction allows the University to maintain a prestigious academic reputation. The deep moral essentialization of “honor” offenses allows the University to brand itself as a noble institution that gives no mercy to liars, cheaters and thieves. However, this framing is not only inaccurate, but harmful.

The fact that single sanction relies on a harsh logic of moral essentialization to justify itself is deeply telling. Ultimately, the Committee is not really interested in cultivating a community of trust. Instead of a University where students can trust that themselves and their peers will receive appropriate sanctions for wrongdoings, single sanction creates a culture of fear. At the University, students fear that a misplaced citation could result in a months-long investigation possibly resulting in expulsion, but are also hesitant to report cheating because they are unsure their classmate deserves the same ordeal. While steps have been taken in recent years to remove single sanction, low voter turnout has prevented any substantive change in the honor system. However, despite student apathy, the harms done by single sanction have not gone away. In fact, with the release of the Committee’s bicentennial report in 2019, those harms — particularly to international students and students of color — are on full display.

Human beings are inherently complex and inherently capable of growth and change, and thus we should begin viewing the solution to honor offenses as rehabilitation, not retribution and automatic exclusion from the University. Just as UJC’s multi-sanction system implies that students who damage property or behave recklessly are capable of growing and changing, students who have lied, cheated or stolen should be given the same treatment. As a result, the single sanction cannot continue.

Emma Camp is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.