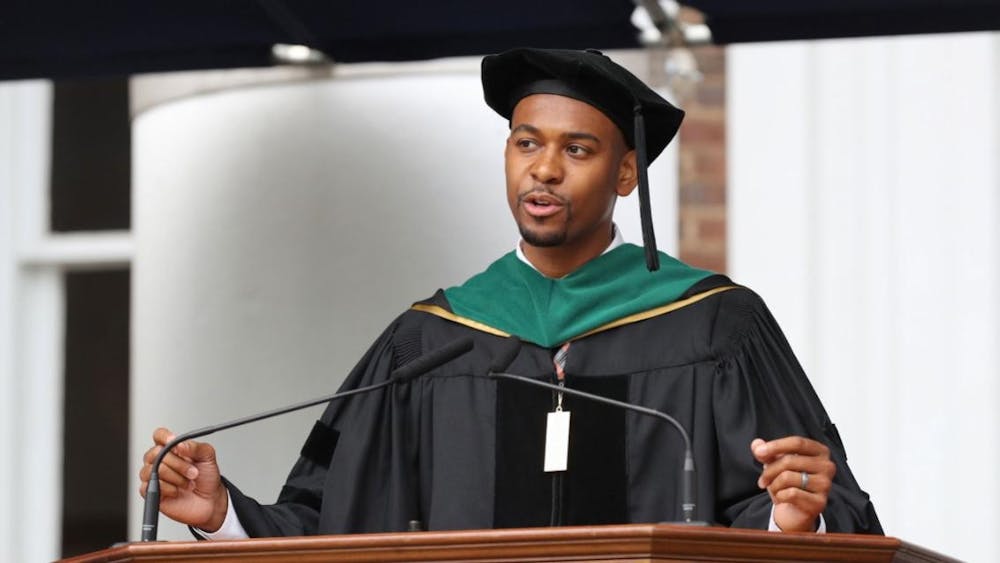

Recently, Dr. Cameron Webb — a professor at the University’s School of medicine — made headlines for winning the Democratic primary of Virginia’s Fifth Congressional District. As a graduate assistant in his research lab over the past year, I think it’s safe to say that I’ve officially come to know Dr. Webb in a variety of settings — a professor, a physician, a potential congressman and most importantly, as a fellow enthusiast of health policy. The buildup to his nomination was undoubtedly exciting within our laboratory family, but I think the novelty of this race’s results bring light to a key fault in our healthcare system — the lack of physician involvement in health policy and legislation.

For centuries, the role of a physician was singular — to cure medical ailments. However, research has shown that only 20 percent of health care outcomes can really be attributed to medical care. On the other hand, health behaviors, sociocultural and economic factors and physical environment are responsible for up to 80 percent of health successes — or unfortunately, failures. Ultimately, it is physicians who are able to recognize which social determinants have disproportionate effects on their patient population and truly understand how these factors manifest in the prolonged care of an individual. As physicians continue to engage these inequities on a daily basis, the importance and necessity of their legal engagement becomes all the clearer — the patients need a voice, and physicians are the best people to provide it.

The insights that physicians have about the realities of health care delivery are unparalleled. From lowering prescription drug costs to navigating occupational hazards, physicians are at the core of individualized care. They have the moral perspective necessary to create more comprehensive and all-encompassing legislation. Their engagement would allow lawmakers to better understand how and why physicians will respond to new policies as well as how new policies impact various groups of patients.

The benefits are irrefutable, so where does the U.S. stand today? Of the 535 members of the 116th United States Congress, 17 are physicians. Only three percent of Congress is represented by physicians, even though health care spending accounts for 17 percent of the national GDP and healthcare was the fourth most important topic to voters in the 2016 presidential election.

Of these 17 members of Congress, two are Democrats while the other 15 are Republicans. Two represent non-Caucasian races and ethnicities, and only one is female. Not only are the number of physicians involved in the legislative process limited, but they are neither demographically representative of the overall physician population nor the country as a whole. How can we expect legislators to solve key issues that disproportionately affect minority populations when communities who are experiencing them are not given a voice?

However, physician advocacy and involvement extend beyond just holding political office. Physicians can engage and coordinate with representatives, write expository pieces through the media, join politically-motivated groups and participate in community-level activism to impact widespread change. But even these methods are often overlooked and disregarded. We often assume that doctors don’t engage with public policy because of a lack of time. While this may be a key contributor, maybe we are ignoring the larger problem at hand — we haven’t created the spaces and opportunities they need to pursue it.

First, we need to promote health policy education within all medical schools, not just the handful of schools with policy-based curricula that stand today. Medical students with an interest in health policy, such as myself, should be encouraged and given the opportunity to pursue health policy through recommended electives or extracurricular programs offered by the University. Institutions should even go so far as to provide resources and connections to outside institutions through externships and fellowships to promote deeper engagement.

Mid-career physicians are an even tougher group to tackle. It is difficult, if not near-impossible, to inspire established physicians to drastically alter their career paths. However, hospitals and academic health systems should expand their definition of scholarship to provide financial and sabbatical-based incentives for physicians who do choose to pursue policy engagement. Not only does this benefit the institution’s scholarly reputation, it also provides clear opportunities for individuals to create change within their local communities in a novel manner.

While these recommendations would create substantial legislative change within the realm of health care, they are by no means all-encompassing. The U.S. has a long way to go if we ever hope to have engaged physicians equipped with both the determination and legislative power to enact meaningful change. The journey towards becoming a world leader in equitable and just health care is a tumultuous one, but for now, we can do our parts in taking the first step — electing those who are already on the forefront, like Dr. Cameron Webb.

Maitri Patel graduated from the University in 2019 and received a Masters of Public Health. She is a rising M1 at the University’s School of Medicine.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.