Following the murder of George Floyd by Minnesota police, America erupted into a furor and outrage. People rushed to protest, demanding change to an intrinsically racist justice and police system. Somewhere in the midst of this righteous anger is a conversation to be had about the place of activism within the music industry, particularly for white and white-passing musicians.

Despite the music industry’s sordid and deep-rooted past with racism, individual artists have often taken stances for racial equality, such as Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” video — where her love interest was a dark-skinned Black man — or Janet Jackson’s 1989 concept album “Rhythm Nation,” which aimed to use music to “break the color lines.” But as generations grow more socially aware, does being a musician create a responsibility in speaking out against racial injustice? The answer is a resounding yes. Racism is still prevalent throughout American society, it just manifests differently. As the landscape of racism changes, the music industry must change how it responds.

Today’s musical artists have more reach and influence than ever before. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, many artists have used their platform to raise awareness — openly supporting organizations like Black Lives Matter, posting and matching donations. Some celebrities like Shawn Mendes and JoJo have even attended protests.

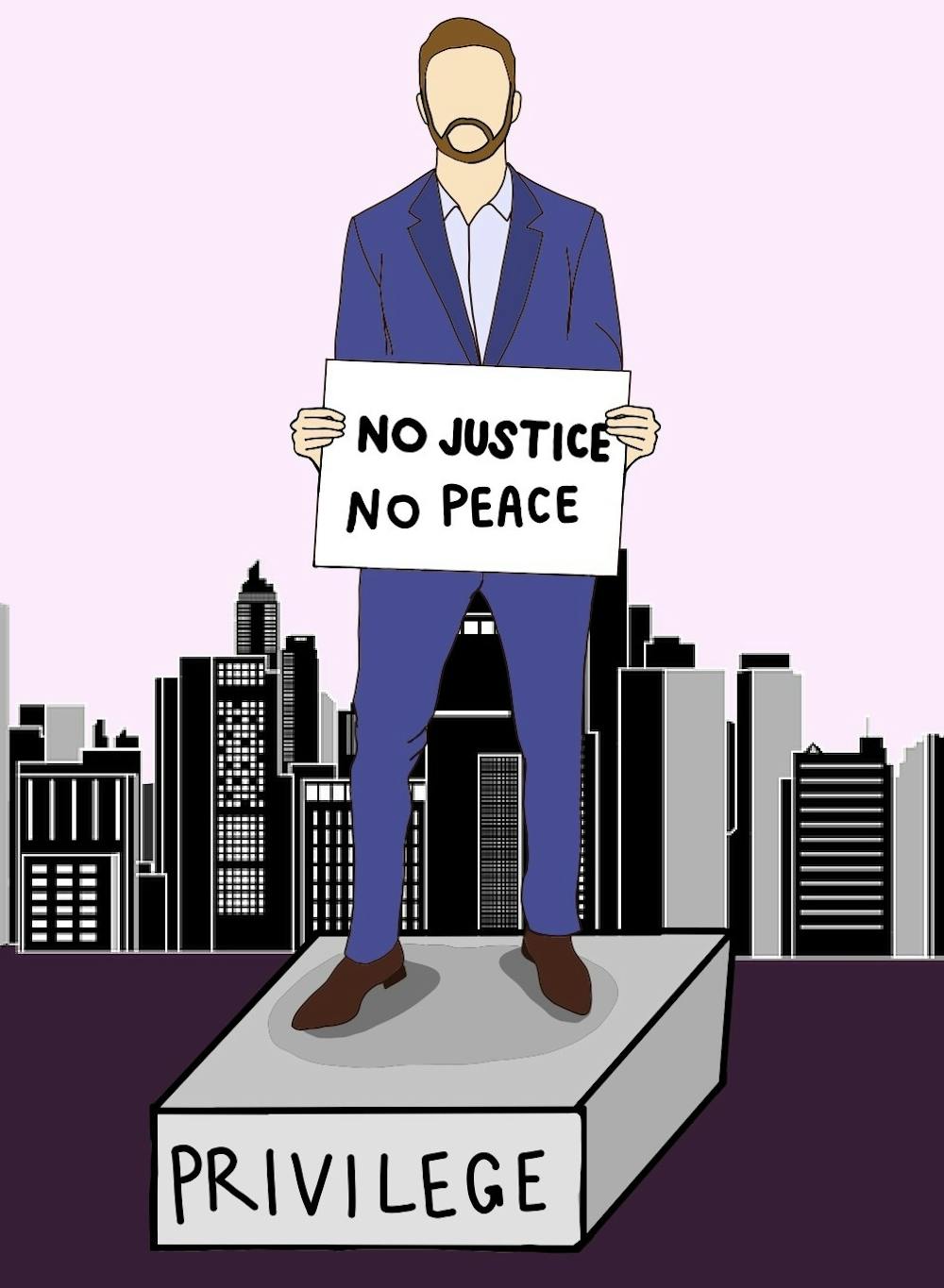

However, awareness and protests are not enough. Activism means nothing if it is not backed up by action. When protests die down, artists cannot resume business as usual. White artists need to actively work to change the systems from which they benefit. They need to take steps to dismantle the racism within a music industry that takes from Black culture but devalues Black artists and music, and they must call out the lack of diversity in institutions like the Grammys and — most importantly — acknowledge how their white privilege positions them to benefit from such things.

Take, for example, Ariana Grande and Justin Timberlake, artists with huge followings and critical acclaim. Both have taken steps to help protesters and the Black Lives Matter movement, though while these actions do not go unnoticed or unappreciated, neither artist has done anything that might threaten the system which privileges them and consequently foster change.

Grande could and should acknowledge how her deepening tan, which corresponded with her transition from pop star to sex symbol contributed to the hyper-sexualization of Black women, as well as how she profits from presenting as racially ambiguous while using a blaccent and making music that would traditionally be considered “Black.”

Likewise, Timberlake must publicly recognize how he profited from both Black culture and artists by building his solo career on the stylings of Michael Jackson, while also capitalizing on the downfall of Janet Jackson by being silent and ultimately complicit in the misogynoir she faced after her wardrobe malfunction at the 2004 Super Bowl. It has been 15 years since the incident and Timberlake has yet to issue a formal apology to Jackson for how he handled the situation.

Even the recording industry is failing to address the root of the problem. The Grammys have changed the name of their Best Urban Contemporary Album category — the category was established in 2012 — to Best Progressive R&B Album. While renaming the category does rid it of the negative connotations associated with the term “urban,” the category itself is still inherently problematic. A “Progressive R&B” category only serves as a vehicle to pigeonhole Black artists who defy genre.

Artists who aren’t doing enough should take notes from Billie Eilish and Halsey. The two artists are white and white-passing, respectively, and are using their platforms to acknowledge their privilege and enact change. Eilish — who won all four major categories at the 2020 Grammys — recently called out The Recording Academy for its racial bias and labeling of Black artists such as Lizzo. Halsey — a biracial woman — established the Black Creators Funding Initiative, which will help amplify the art and voice of Black artists — something record companies fail to do. These actions may not solve racial inequality within the music industry, but they are a step in the right direction.

Ultimately, the racial inequality within the music industry is not as pervasive a problem in comparison to issues like voter suppression in minority communities or reforming a legal system that unjustly punishes Black citizens with harsher sentences. But racial injustice is embedded in the fabric of American society and it must be confronted in every form.