On a late night in the fall of 2018, just as the semester was wrapping up, a Black first-year student was studying for final exams at Alderman Library when he decided to walk back to his Alderman Road dorm as the library was about to close. For no particular reason, he decided to traverse the full length of adjacent McCormick Road rather than taking a shortcut through the McCormick Road residence halls commonly used by students. Not long after he started walking, the student — who asked to be identified only as Publius for this story — said something didn't feel quite right.

“I got this weird feeling like people are looking at me,” he told The Cavalier Daily. “You ever get that feeling like you're being watched?”

As he neared Clark Hall, Publius turned around and found a University Police Department vehicle creeping along the road just behind him. He quickly did a self-check to ensure he had his phone and student ID with him should he be questioned by the officer in the vehicle.

“I’m like, OK, that’s a little weird, but I’m just going to keep on truckin’ and look as non-suspicious as I possibly can,” he said.

By the time Publius reached the McCormick Road bridge, he said the vehicle would quickly speed up at times but then slow down again each time he turned around to look at it. At this point, Publius said he felt concerned for his personal safety so he decided to text a friend who lived in the nearby Bonnycastle residence hall and asked if he could quickly meet him near the dorm at the end of Bonnycastle Drive.

“[I said] ‘UPD is following me, and I don't feel comfortable’...‘I don't know if I'm going to be able to keep this up the whole way to new dorms’,” Publius recalled.

However, once Publius turned down Bonnycastle Drive to meet his friend, so too did the UPD vehicle. As he approached his friend’s dorm, Publius said the white officer behind the wheel rolled down his window and asked if he was lost, to which Publius responded that he was just waiting for a friend to work on a project. The officer further pressed him, asking, “Are you sure? Because it seems like you don't really know where you're going,” and added, “We don’t want any suspicious activity going on tonight,” according to Publius.

“My anxiety was kicking in,” Publius said. “[The officer] had this ‘you're about to do something, I advise you not to do it’ tone in his voice.”

As he stood frozen on the steps leading to Bonnycastle residence — afraid that any sudden movement might prompt the officer to exit his vehicle — Publius’s friend rushed out and asked if there was a problem.

“Something in my spirit was like ‘I just need to either not say anything or not move’,” Publius said.

After Publius’s friend intervened, the officer then promptly said there was no problem, telling the two to ‘have a good night’ before quickly speeding off in his vehicle, according to Publius.

Although Publius said that he hasn’t had any interactions with UPD personnel since the incident occurred in 2018, he added that he still feels nervous whenever he sees UPD officers around Grounds. He also said that he never bothered to file a formal complaint with UPD or the University about his interaction as he felt it would likely fall on deaf ears. In an email to The Cavalier Daily, University spokesperson Brian Coy said that neither UPD or the Office for Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights were aware of any complaint comparable to Publius’s, adding that it is impossible to verify an anonymous allegation of misconduct if no complaint is filed. However, Coy said that if Publius decided to file a complaint, “the University would review the matter with the seriousness it deserves.”

“The only thing I remember from the officer that was talking to me is his voice so everytime I see them physically, it's like, ‘Is that the guy?” Publius said.

However, Publius said he considers himself lucky for only having one bad experience with UPD personnel in recent years, adding that many of his Black friends were subjected to much worse treatment on multiple occasions, such as being repeatedly racially profiled by UPD officers who followed and questioned them while walking home from the Corner, even if they hadn’t consumed alcohol and were over the age of 21.

A recent survey revealed at least 54 complaints of alleged misconduct by UPD, including racial bias and excessive force. (Photo by Sophie Liao | The Cavalier Daily)

Based on responses to an anonymous survey being conducted by Student Council’s Student Police Advisory Board, the experiences of Publius and his friends may not be uncommon at the University. In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Emily Leventhal, a rising second-year College student and chair of the safety and wellness committee that oversees the advisory board, said that they have received 54 student complaints, many of which detail “Personal stories about [UPD officers] harassing [Black, Indigenous and People of Color], using unnecessary force and repeatedly ignoring complaints of sexual assault.”

Leventhal also said that many of the complaints from students of color involved times they were harassed on multiple occasions for issues they had no relation to, while other complaints noted that multiple students witnessed their friends of color be singled out by UPD officers, even if they themselves were not targeted.

“Many students, specifically BIPOC students, said they felt threatened and anxious around officers whose job it is to make them feel safe,” Leventhal said. “Ultimately, they felt that UPD actively looks to intimidate and punish students, rather than simply keep them safe.”

Likewise, Publius said that many of his hallmates during his first year at the University — the majority of whom he said were white — were unaware of or did not understand the fraught relationship between students of color and the police, as they had never had such a negative experience themselves. In particular, he said the disparity in the treatment of white students and students of color by UPD officers while on the Corner was stark.

“I purposely don't go on the Corner to avoid it,” he said. “I avoid the areas and specific locations that I know they are usually around and near Central Grounds. Starting my second year, I purposely avoided those areas so that I wouldn’t come across U.Va. police.”

The Student Police Advisory Board, which hopes to bring about greater transparency from UPD and hold the department accountable for its actions, is slated to present the complaints to UPD at a meeting in August. In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Tim Longo, chief of the University Police Department and associate vice president for safety and security, said he had not yet seen the complaints set forth by students in the Student Police Advisory Board’s survey, but added that investigations of use of force in particular take place whether or not a formal complaint is submitted to UPD.

Based on data from 2019, UPD received eight complaints that were investigated but did not record any use of force reports, according to Ben Rexrode, crime prevention coordinator for the department. However, the exact nature of the complaints is unclear, and it is unknown if UPD took any disciplinary action against officers as a result. In an email to The Cavalier Daily, Longo declined to provide further detail regarding the complaints or the outcomes of the investigations, citing the withholding of personnel records from the public under Virginia law.

“As far as excessive force complaints go, I have not seen complaints of excessive force,” Longo said. “We conduct an investigation of every use of force incident that occurs, whether it generates a complaint or not. It’s best practice to conduct use of force investigations, regardless of whether there are complaints, [and] certainly if there are incidents of force that folks seem to believe were excessive or unreasonable. There is a mechanism to make a complaint and have that complaint thoroughly investigated, and certainly we take that very seriously. I take all complaints very seriously though, particularly complaints of bias or force.”

With regards to the processing of complaints in general, Longo said that UPD has an internal affairs body responsible for investigating complaints submitted by members of the University community but also for those generated internally within the department. In accordance with University policy, Longo added that UPD collaborates with several agencies at the University when investigating a complaint — including Human Resources, the Office for Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights and the Title IX office — to ensure that there is independent oversight in the investigation process.

“If a supervisor, for example, discovers a departure from policy or some misconduct [by an officer], that's an internally generated complaint, as opposed to an external complaint which could come from a citizen,” Longo said.

Ultimately, Longo said that all complaints come before him for final review as well as any disciplinary action against UPD personnel, in accordance with the standards and requirements of the Human Resources department.

None of the survey responses submitted to the Student Police Advisory Board mentioned filing a formal complaint with the University as a result of their experiences with UPD, according to Leventhal.

“As we’ve seen across our country, filing complaints directly to the police department is not usually successful in achieving justice,” Leventhal said. “Police officers tend to protect their own so simply reporting officers to the department does not mitigate the gross acts of police brutality. The reality is that officers across the country — even those who have murdered citizens — have not been held accountable for engaging in excessive force or racial profiling, which can be extremely discouraging for students thinking about making complaints to UPD.”

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, less than eight percent of all complaints of police misconduct in the U.S. result in any disciplinary action against accused officers.

Leventhal added that the advisory board hopes to establish its own reporting system to allow students to submit complaints directly to University administration — such as the Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusions or the Office of the Dean of Students — rather than through UPD.

However, Longo said that there is no single manner or method for members of the University community to submit complaints or concerns regarding UPD misconduct, adding that he believes the process should be flexible to allow for any complaints or concerns to be submitted in a way that is most comfortable for the individual involved. For example, Longo said students could use the University’s online reporting mechanism Just Report It — which allows members of the University community to anonymously report incidents related to sexual assault, violence and bias, among other things — to report police misconduct or mistreatment.

“There's not — and in my opinion nor should there be — any prerequisite or required step you must take,” Longo said. “Any way in which you wish to share a complaint is a way in which to share a complaint. Is it a phone call? Is it in an email? Is it through Just Report It? Is it coming to the police station and filing a written report? All those ways are ways in which we receive complaints.”

Longo emphasized that members of the University community can report incidents involving UPD personnel that simply made them feel uncomfortable or didn’t seem to be handled appropriately — even if the conduct was not necessarily illegal or against University policy — and ask for them to be investigated.

“Maybe your policy doesn't reflect the expectations of this community, and if that's the case, you need to look at that,” Longo said. “I think you need to open yourself up to have that kind of discussion. Otherwise, it prevents the department from moving forward, and it prevents the department from having that relationship that’s so critically important to the community that you have to partner with on a regular basis.”

Nonetheless, Leventhal said the majority of students who submitted complaints to the Student Police Advisory Board support recent calls across the country to defund police departments, adding that most respondents called for the reallocation of funds from UPD in favor of alternative health and safety resources, such as the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services.

“Students are angry about the lack of transparency and accountability within the department, the over-policing of students of color and the current inadequate system for resolving sexual violence cases,” Leventhal said.

Graphic by Angela Chen | The Cavalier Daily

32 percent of arrests made by UPD in 2019 were of Black individuals — or 45 out of 142 total arrests — while 66 percent of arrests were of white individuals, according to data obtained by The Cavalier Daily from UPD. Latinx and Asian American individuals, combined, made up two percent of arrests. By comparison, the University’s student body is roughly 6.5 percent Black and the City of Charlottesville is just under 20 percent Black. Of the Black individuals arrested, five were women, or about ten percent of the total number of Black individuals arrested. This trend is observed across all of the arrests as about 80 percent were of men.

Among all arrests made, the most common offenses were drunkenness and other alcohol-related incidents, trespassing and about a dozen cases of marijuana possession. These offenses were among the most common for Black individuals who were arrested as well.

Of the 45 Black individuals arrested, 38 of those arrests were made by white officers, or 84 percent. About 75 percent of UPD’s sworn police officers are white, while 22 percent are African American, according to 2020 data from the department. At least one officer is Asian American, while another is listed as “other.”

Although it is unclear exactly how many of the arrests involved students at the University, just over half of all arrests made were of individuals between the ages of 18 and 29, while slightly less than half of Black individuals arrested were within the same age group. At least one-third of all arrests were made at or within the immediate vicinity of the U.Va. Health System — which UPD has jurisdiction over — while just under 30 percent of arrests took place in the general vicinity of the Corner along University Avenue, West Main Street and 14th Street.

While UPD does not currently keep track of whether or not an arrested individual is a student, faculty or staff member at the University, Longo said he hopes for UPD to find a way to begin collecting that data by the end of this year, as was the case when he served as Charlottesville’s Police chief.

“I want to know how many of these are [students] because one could argue that it's one way of measuring student conduct outside of the [University Judiciary Council],” Longo said. “Do our students, when they're off our Grounds in the community — are they reflecting University values? Are they behaving in a way that's compliant with community values, norms and laws?”

With regards to examining racial disparities in the arrest data, Longo said it’s difficult to establish a baseline for when arrest numbers are disproportionate to understand the full extent of potential disparities in the data due to UPD’s unique jurisdiction over the University community, as well as portions of surrounding Albemarle County and the City of Charlottesville.

“I guess the first question would be disproportionate in what regard?” Longo asked. “Disproportionate to the broader community? Disproportionate to the representation of race and ethnicity on Grounds? It's really kind of hard to look at just the raw data and come to a determination as to whether or not there's an actual racial disparity. The numbers certainly show a disparity of some sort, [but] you really need to drill down into the event itself to see exactly how the arrest took place… and evaluate them on their own merits to really discern whether there's an intentional disparate treatment of an individual.”

More specifically, Longo noted that 22 of the 142 arrests — 15.5 percent — made by UPD in 2019 involved the servicing of a warrant issued by a court order from another locality, in which UPD officers are carrying out the mandate of a judge rather than making an arrest of their own accord or in response to a reported crime. The majority of these arrests tend to take place at the U.Va. Health System as a warrant may be issued for individuals receiving medical care after being involved in a criminal incident, such as driving under the influence. Ten of these 22 arrests were of Black individuals in 2019, although most were unlikely to be University students because of their ages.

Moving forward, Longo said he wants UPD to begin collecting additional data and providing context to it so that the department can conclusively determine whether or not its statistics reveal any racial bias on behalf of its officers or those who are reporting alleged crimes.

“And to do that, you got to drill down into the ‘why was the arrest in issue?’” Longo said. “What prompted it? What were the facts and circumstances that lead to it? Even those things that don't result in an arrest to make sure there's a narrative document that a supervisor, a citizen, a police chief or a judge can look at, and read and determine the facts and circumstances that resulted in an officer taking a particular course of action.”

Longo added that the effort to expand UPD’s data collection and make the process more transparent is also being prompted by a new law passed by the Virginia General Assembly earlier this year — and took effect July 1 — that “prohibits law-enforcement officers and state police officers from engaging in bias-based profiling” and mandates that law enforcement agencies in the Commonwealth begin reporting data to the state regarding vehicle and investigatory stops and records of complaints relating to the use of excessive force by officers. More specifically, officers will be required to collect a variety of data and information during any stops, including the race of those involved, the reason for the stop, if a search was conducted and whether an arrest was made and on what charges.

Graphic by Angela Chen | The Cavalier Daily

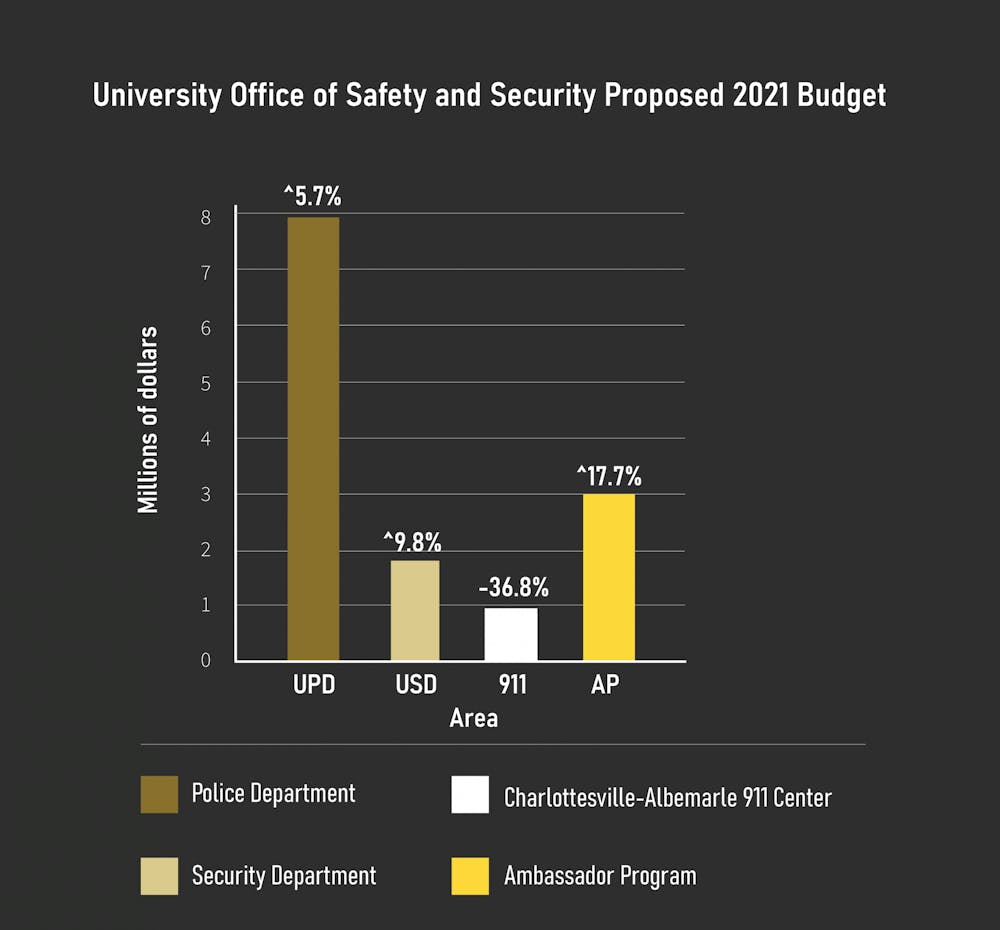

In terms of UPD’s proposed budget, overall funding for the Office of Safety and Security at the University — which includes UPD — had a total budget of $11,807,678 in 2019 and increased to $15,577,490 in 2020. For both 2019 and 2020, just over half of the annual budget — $7,323,764 and $8,883,519 respectively — was set to be allocated specifically to the police department. The department’s operating expenses were set at $1,051,056 in 2019 and increased to $1,653,217 in 2020.

In addition, the police department was also set to receive $750,000 in 2019 and 2020 for services provided at John Paul Jones Arena during athletics events.

The police department’s executive salaries budget, which includes the chief and the deputy chief of police, increased from $159,135 in 2019 to $560,423 in 2020. As of 2020, Chief Longo has a salary of $285,000, whereas his predecessor Tommye Sutton had a salary of $185,000 in 2019. However, Sutton did not also serve in the capacity of associate vice president for safety and security at the University as Longo currently does.

In addition to UPD, the remainder of the office’s budget is used to fund the operations of the security department — which employs several dozen unarmed security patrol personnel around Grounds — the jointly-operated Albemarle-Charlottesville-UVa. 911 Center and the University’s Ambassador program, which is externally contracted by RMC Events. The security department had a budget of $1,679,365 in 2019 and $654,523 in operating expenses. For 2020, the department had a budget of $1,902,017 and $885,523 in operating expenses. In addition, the security department was also budgeted to receive almost $2.5 million in outside funding from the U.Va. Health System in 2019 and 2020, based on a memorandum of understanding the two entities have to provide security services at the hospital.

Meanwhile, the Albemarle-Charlottesville-UVa. 911 Center was budgeted $1,177,903 in 2019 and $1,517,218 in 2020. The Ambassador program was budgeted $1.6 million in 2019 — which was also supplemented by an anonymous donation of $879,395 for a total of $2.4 million — and $3,248,000 in 2020 following the expansion of the program to include patrols of first-year residence halls at the University.

In terms of actual spending, the University Police Department spent $7.27 million in 2019 — $2.64 million of which was in operating expenses and $4.63 million in officer and staff salaries. Funding for $860,000 of these expenditures came from outside revenues and recoveries. By 2020, police department spending had increased to $7.85 million — $2.36 million of which was in operating expenses and $5.49 million in officer and staff salaries. Funding for $320,000 of these expenditures came from outside revenue and recoveries.

For both 2019 and 2020, the police department was budgeted to have 77 sworn police officers, although the department has had between 50 to 60 officers since 2019 due to an ongoing personnel deficit. In addition, there are also 25 paid staff members at UPD, including service clerks, camera control officers and business staff. However, thanks to $1.2 million of investment in officer salaries during the past three years, the police department currently has 62 officers. Since 2017, the bulk of UPD’s budget increases have been allocated towards officer and staff salaries.

The security department spent a total of $3.55 million in 2019, including $170,000 in operating expenses and $3.38 million in personnel expenses. Funding for $2.3 million of these expenditures came from outside revenues and recoveries, such as the agreement with the U.Va. Health System. In 2020, security department spending had increased to $3.89 million with $390,000 in operating expenses and $3.5 million in personnel expenses. Funding for $2.25 million of these expenditures came from outside revenues and recoveries.

For the regional emergency system, spending increased from $1.18 million in 2019 to $1.52 million in 2020. The Ambassador program saw $1.6 million in spending during 2019 — in addition to the nearly $900,000 anonymous donation — and increased to $2.54 million in 2020.

As for Longo’s proposed $14.75 million budget for the Office of Safety and Security in 2021 — which has yet to receive final approval from University leadership but is expected to be adopted in the coming weeks — projected spending includes $8.65 million for the police department, or an increase of about 20 percent from 2019 when including outside revenues and recoveries.

Graphic by Angela Chen | The Cavalier Daily

Meanwhile, $4.17 million has been proposed for the security department, $2.99 million for the Ambassador program and a reduced $960,000 for the regional emergency system. For the police department and security department, $690,000 and $2.37 million — respectively — of these proposed expenditures are expected to come from outside revenues and recoveries, rather than being directly funded by the University.

Longo said he is prioritizing closing UPD’s longstanding personnel deficit with regards to both sworn police officers and security officers, especially as it relates to security personnel in the U.Va. Health System. He added that he hopes to find more creative ways to utilize the Ambassador program beyond the typical foot patrols of locations around the University — such as Central Grounds, the Corner and 14th Street — to fill in some of the existing personnel gaps.

“So I think that's a big way to compliment our public safety resources is utilizing the ambassadors for that purpose … to make sure we're effectively utilizing that resource the best way that we possibly can, keeping in mind that it's a third party contract — we don't hire them — but we do have some say in how they get deployed,” Longo said.

Students and community members gather at the Rotunda June 7 for a demonstration against Confederate monuments and police brutality. (Photo by Geremia Di Maro | The Cavalier Daily)

In the wake of the May 25 murder of George Floyd at the hands of a white former Minneapolis police officer, protests calling for racial justice and an end to police brutality erupted across the country in the weeks that followed, including in Charlottesville and at the University. Among the many demands set forth by demonstrators, perhaps the most prominent has been the call to defund the police, as demonstrated through a ‘Defund the Police Block Party’ that was organized by rising second-year College student Zyahna Bryant and Radford University student Trinity Hughes outside of John Paul Jones Arena June 13.

In early June, a group of predominantly Black student activists submitted a statement and list of demands to a racial equity task force recently formed by University President Jim Ryan after the statement garnered more than 1,900 signatures from University community members and 180 signatures from student organizations. The group of students had initially published their statement and list of demands June 1 in response to a statement by Ryan addressing nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd. In their response, the students expressed disappointment towards Ryan’s initial statement and called upon him and the University to not “be complacent when it comes to fighting against systemic racism and inequality, which the University regularly fails to do.”

Independent from the list of demands published by the Black student activists, the Black Student Alliance also issued a “Reiteration of Historic, Yet Unmet Demands” June 1 calling on the University to fulfill several demands that student activists have been advocating in favor of for decades.

“For over half a century, Black students at the University of Virginia have worked tirelessly to improve the Black student experience and voice their concerns over a lack of support,” the BSA statement reads. “The constant failure of the University to turn verbal affirmation of its dedication to diversity into genuine efforts to address the history of racial discrimination at UVA is more than telling. It is not enough to solely acknowledge the systemic inequality and racism facing and killing Black Americans.”

Neither the Black student demands nor those reiterated by the BSA explicitly reference defunding of the University Police Department, although the former requests that an “appropriate amount” of funding used for policing on Grounds be reallocated to social services and community programs instead.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Sarandon Elliot, a rising-fourth year College student and one of the authors of the Black student demands, said that she supports reallocating funds away from UPD to invest in social services and community programs at the University — such as the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services and greater funding for African American studies. As a starting point for the University to defund and divest from both UPD and the Charlottesville Police Department, Elliot pointed to the recent decision made by the University of Minnesota to sever ties with the Minneapolis Police Department, including no longer asking for their officers to assist with large events such as athletic games and concerts.

Elliot said that if she could speak directly to University President Jim Ryan and Chief Longo regarding policing at the University, she would emphasize the importance of listening to the voices of Black and Brown students when they express their fears and concerns on the matter.

“Just as a Black woman on campus — as someone who has grown up in an overpoliced neighborhood that has seen the police be inactive and really only benefit rich, white people — I understand that you don't get these experiences as white men in places of power,” Elliot said. “Especially with U.Va. being so elitist and its history of racism, I get that you don't get that, but you need to start listening to Black and Brown students on Grounds when they say this is a problem … We’re not doing this for fun, we're not writing these letters and petitions for fun, we’re not complaining for fun — it's because we genuinely feel in danger around the police, and no student on U.Va.’s campus should feel like they're constantly at risk when they run into the police.”

Speaking on Longo’s currently proposed budget increases for UPD — an increase of about 10 percent from 2020 when including revenues and recoveries — Elliot said the increase in funding for law enforcement personnel in the wake of several weeks of racial justice protests across the country was telling of the University’s priorities.

“That also tells me that Tim Longo is absolutely tone deaf,” Elliot said. “The fact that he would suggest … to expand it, I think that’s a joke, and it shows how out of touch the police are with the community.”

However, in response to nationwide protests calling for the defunding of police departments, Longo said that increasing violent crime rates in cities across the country — such as an uptick in deadly shootings in several U.S. cities in recent weeks — emphasizes an ever growing need for law enforcement agencies to ensure public safety.

“[The] tremendous amount of violent crime clearly underscores the role of the police and preserving safety,” Longo said. “At the end of the day, that has to be a priority for us. I mean, we are a city within a city. On any given day, there's 50,000 people on these Grounds, and there ought to be a focused group responsible for safety and well being, and the programs that ensure safety and well being — but do that in a way that reflects the values of our student body and our faculty and our staff and the people who come here.”

As a means of divestment from area law enforcement, both sets of demands call for the University to reevaluate — or otherwise terminate — its relationship with the Charlottesville Police Department and other law enforcement agencies as a result of historical racial bias and excessive use of force in their policing practices. Like Elliot, the BSA demand also calls on the University to follow the example of the University of Minnesota to divest from and demilitarize the police by barring any outside law enforcement agencies from coming onto Grounds. More specifically, it quotes language from the 1970 Virginia Strike Committee May Day Demands, which call for complete and total non-cooperation between the University and a slough of law enforcement agencies.

“We demand that you, as president of the University, prohibit its security police force from carrying firearms, and the University not allow any outside law enforcement officers on its property — FBI, CIA, National Guard, Virginia State Police, Charlottesville-Albemarle County Police, etc.,” the demand reads.

In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, Deric Childress Jr., a rising third-year College student and BSA vice president, said that the existing relationship between the University and Charlottesville Police Department in particular is problematic given the agency’s track record in recent years, as stated by both the BSA and Black student demands.

In recent years, the relationship between the Charlottesville Police Department and the surrounding community has been especially strained amidst racial disparities in stop and frisk and use of force data and what many community members consider to be over-policing in general. For example, CPD, UPD and other regional law enforcement agencies were heavily criticized in 2018 for the overwhelming display of police personnel at anti-police protests on the one-year anniversary weekend of the white supremacist Unite the Right rally. However, one year earlier, law enforcement personnel failed to intervene when violent clashes broke out between attendees of the rally and anti-racist counterprotesters in downtown Charlottesville. More recently, both CPD and UPD have been criticized for their covert cooperation with the Virginia State Police during the Defund the Police Block Party in June.

According to Tyler Hawn, public information officer for the Charlottesville Police Department, UPD, CPD and the Albemarle County Police Department currently have a mutual aid agreement that has been in effect since 1995, although he emphasized that CPD does not have any contractual obligation to patrol the University’s Grounds. Moreover, the mutual aid agreement — known formally as a Memorandum of Understanding — does not contractually bind any of the three agencies to abide by the agreement’s terms. According to the agreement, any of the three agencies could withdraw at any time, provided that they give at least 90 days notice of such intentions.

“The Charlottesville Police Department does not have a contractual obligation to patrol UVA’s grounds, nor has UVA’s leadership reached out to our department to discuss our Memorandum of Understanding (MOU),” Hawn said in a statement. “For clarity, the Charlottesville Police Department is not the primary investigating agency for crimes that occur on Grounds or on University property, only off-Grounds and areas that are not University property.”

The relationship between CPD and UPD tends to be structured around individual requests for assistance from UPD, according to Charlottesville Police Chief RaShall Brackney. More specifically, Brackney said UPD might request assistance or resources from CPD when investigating higher level crimes on Grounds such as sexual assaults or shootings.

However, UPD repeatedly declined offers of mutual aid assistance from CPD on the night of Aug. 11, 2017 when white supremacists marched on Grounds and assaulted students at the base of the Thomas Jefferson statue on the north side of the Rotunda. In a scathing review of Charlottesville’s response to the white supremacist demonstrations of 2017, Tim Heaphy, a former U.S. attorney and current University counsel, said UPD underestimated the potential for conflict Aug. 11 and failed to request assistance from CPD until after violent clashes had already broken out.

More recently, UPD, CPD and the Albemarle County Police Department entered into a “Unified Command Agreement” to provide mutual aid resources amongst the three agencies specifically in response to the Defund the Police Block Party in June. Since the event was initially hosted on University property at John Paul Jones Arena, Longo oversaw the planning process for the law enforcement response to the demonstration and made the controversial decision to invite the Virginia State Police to assist UPD, CPD and ACPD personnel that day. In response to the block party in June, UPD spent just over $28,000, while CPD spent almost $27,000 to manage the event.

In addition to the original 1995 mutual aid agreement, the agreement that UPD entered into with CPD and ACPD to respond to the block party was enabled by the 2013 Regional Emergency Operations Plan, which outlines the structure and process for the University, the City and the County to jointly-respond to a variety of public safety emergencies in the greater Charlottesville area. Revised in late 2017 in the wake of the disjointed response by law enforcement agencies to the white supremacist Unite the Right rally, the plan also structured the regional response and its massive police presence during the one-year anniversary of the rally in 2018.

In a statement to The Cavalier Daily, Wes Hester, deputy spokesperson and director of media relations for the University, said cooperation between UPD and local law enforcement agencies is essential due to the University’s location along the municipal boundaries of both the City of Charlottesville and Albemarle County.

“Our police and public safety staff are dedicated and well-trained in keeping students, faculty, staff and community members safe in a manner that respects the sanctity of human life and reflects the values of professionalism, dignity, humility, and compassion,” Hester wrote. “Given our geographic location in both the City of Charlottesville and the County of Albemarle, we rely closely on our interagency collaboration, joint service agreements, and strong relations with other local law enforcement agencies.”

According to the 1995 agreement, police support provided among the three jurisdictions could include “uniformed officers, canine officers, forensic support, plainclothes officers, special operations personnel and related equipment.” It also states that the three agencies agree to provide “assistance to the requesting jurisdiction in situations requiring the mass processing of arrestees and transportation of arrestees … [and] to assist the requesting jurisdiction with security and operation of temporary detention facilities.”

If a law enforcement officer is present in a jurisdiction other than their own, the officer has the power to make arrests only in cases where there is “an apparent, immediate threat to public safety [that] precludes the option of deferring action to the local police agency,” according to the agreement. However, if one agency specifically requests police assistance from one or both of the other agencies, then law enforcement officers from an assisting agency have the same powers as those in the jurisdiction being assisted.

However, Longo said that a reinterpretation of the original 1995 agreement in the mid-2000s — while he was Chief of the Charlottesville Police Department — expanded the area under UPD’s jurisdiction to include not only Grounds and other University property, but also portions of the City of Charlottesville such as the Corner, Rugby Road, 14th Street, Madison Avenue, 10th Street, Wertland Street, portions of Preston Avenue and several other nearby sidestreets where students typically reside. As a result, he added that cooperation between UPD and CPD takes place on a daily basis rather than solely in situations where one of the agencies requests assistance from the other.

“I've over the years have said many times that because of the necessity of bringing three police agencies together to deal with the many things that occur on Grounds throughout the year, whether it be a concert or an athletic event, day to day interactions are really critical to ensuring that activity is somewhat seamless,” Longo said. “The agreement with the city and the county and mutual aid agreement allows us to share resources when the need arises.”

While the agreement does not specify specific financial parameters for providing assistance to one of the three agencies, one clause states that the agencies — unless previously agreed upon — “shall not be liable to each other for reimbursement for injuries to personnel or damage to equipment incurred when going to or returning from another jurisdiction … [nor] be liable to each other for any other costs associated with, or arising out of, the rendering of assistance.”

In response to anti-police demonstrations at U.Va. and in Charlottesville during the one-year anniversary of the white supremacist Unite the Right rally, CPD and UPD formed a Unified Command Agreement with ACPD, Virginia State Police and the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, with CPD and UPD each spending approximately $921,000 and $422,000, respectively. It is unclear how much of these funds were used to support assisting law enforcement agencies, although the University did provide accommodations for hundreds of State Troopers for several days at Lambeth Field Residences in Aug. 2018.

Among other things, Childress said the failure of UPD to protect student demonstrators on the night of Aug. 11, 2017 and the militarized response of law enforcement personnel during the one-year anniversary weekend of the rally have been central to worsening the already-fraught relationship between students of color and UPD, adding that students should not be subjected to such confrontational treatment by police.

“When you're at a university, you’re dealing with students,” Childress said. “There's some sort of a negative connotation or fearful connotation when Black people or POC on Grounds see policemen — like we don't see them as a sense of comfort, we see them as a sense of threat or unprotection.”

Citing her personal experiences with police while growing up in Richmond, Va. — a city that has seen a spate of violent clashes between police and protesters in recent weeks — experienced Elliot said that she and other students of color on Grounds have a fundamentally negative view of law enforcement that others who do not come from a similar background likely don’t understand.

“Growing up in a Black working class neighborhood, the police were really just there to harass us and to harass young Black kids and not really protect us,” Elliot said. “So just in general from that perspective, I've kind of grown up [thinking] that the police are not meant to protect us — people that look like me.”

University Police Chief Tim Longo has only been in his current role since February — when he was promoted to his position as chief and associate vice president for safety and security at the University — after serving in an interim capacity since October. Prior to his appointment, Longo served as Charlottesville’s police chief for 15 years before retiring in 2015.

Longo and the Charlottesville Police Department garnered national attention during the search for Hannah Graham — an undergraduate University student who was abducted and murdered by Jesse Matthew in Charlottesville in September 2014. Longo was also police chief during the case of Yeardley Love, a University student who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend, George Huguely, and the case of Morgan Harrington, a Virginia Tech student was also abducted and murdered by Matthew.

Tim Longo, former chief of the Charlottesville Police Department and the current chief of the University Police Department, speaks at a press conference during the search for Hannah Graham in 2014. (Photo by Marshall Bronfin | The Cavalier Daily)

Prior to his time in Charlottesville, Longo began his career in law enforcement while enrolled at Towson University, working as an administrative clerk for the Baltimore Police Department and later serving as a patrol officer and police commander. However, Longo’s affiliation with the Baltimore Police Department stirred controversy in 2015 when he was called to testify in the case of BPD officer William G. Porter in relation to charges Porter faced stemming from the death of Freddie Gray — a young Black man who died after receiving fatal spinal injuries in BPD custody. Despite pleas for medical attention, Porter and another officer restrained Gray and loaded him into the back of a police van after being arrested for unclear reasons.

Longo testified that Porter was not responsible for Gray’s death as he had notified those who were primarily responsible for Gray's care that he needed medical attention and exercised his discretion in deciding not to secure Gray with a seat belt — even though BPD policy stated that he should have been secured with one. "I believe [Porter's] actions were objectively reasonable under the circumstances he was confronted with," Longo said during his 2015 testimony, according to The Baltimore Sun.

“That literally is insane to me,” Publius said on Longo’s involvement in the Freddie Gray case. “Your main concern should be about your students and how your students would feel about that, but it’s not and it's not publicized so … U.Va. needs to start thinking of their students and putting their students first and in order to do that, they really have to reexamine and redefine police institutions.”

In a statement to The Cavalier Daily, University spokesperson Brian Coy said Longo’s extensive experience in law enforcement and service as an expert witness in several related cases were assets to his current role of overseeing policing and public safety at the University.

“Prior to assuming his current role at the University, Chief Longo served as an expert witness in both criminal and civil matters related to police policy, practice, training, investigations, supervision and a host of other issues related to policing,” Coy wrote. “His work was on behalf of prosecutors and plaintiff’s counsel, and in some cases involved the defense of involved officers, agencies and municipal governments. The fact that his expertise was sought in a variety of cases involving alleged police misconduct is a reflection of his national reputation as an impartial expert on these matters. In the midst of a national conversation about the proper role of police in our society, the University is fortunate to have a leader with Chief Longo’s wisdom and experience leading our public safety services."

In terms of fostering a more trusting and positive relationship between UPD and students of color on Grounds, Childress said officers need to undergo more intensive de-escalation training and make a concerted effort to get to know students of color at the University.

“We need to have a relationship between the POC community and the police force,” Childress said. “There needs to be social interaction and social connection so we can get to know them — like I can't name one UPD officer on Grounds, and it's not because I'm not open minded about it.”

Childress added that it was unnecessary for officers to be armed when interacting with students on a day-to-day basis as it often only further intimidates them during interactions with police. Currently, UPD employs 62 sworn police officers who are typically armed at all times when on duty. In addition, UPD also employs a few dozen security officers who are not authorized to make arrests as are sworn officers and do not carry any firearms or other weapons.

Childress said that — while he has not personally experienced any mistreatment at the hands of UPD personnel — he knows many friends who have had negative experiences. Childress added that he believed many of the interactions could have had better outcomes if UPD officers were less confrontational in their approach to policing.

“How UPD and how police across Grounds communicate with students is very militant, and it’s very controlling,” Childress said. “Maybe if you just approach a situation very level headed then maybe the whole interaction, or maybe the whole situation can be looked upon differently. Because there have been many instances where I've had friends who have been in situations where UPD is present and the way they’re treated is very unfair, and they feel like it’s very much so because of the color of their skin.”

Childress emphasized the need for UPD personnel to focus more upon building trust and comfort with students of color at the University and being less confrontational in their policing. In particular, he said that UPD needs to go out of its way to establish a positive relationship with students of color.

“When it comes to things like this, they need to be in positions where they are present and … where they are in our spaces so we can get to know them better,” Childress said. “UPD has not made any effort of getting to know the Black or POC community on Grounds so I feel like in order for the relationship to be created, that needs to happen.”

On the matters of training and policing practices at UPD, Longo said that all UPD personnel have received both bias and cultural awareness training, in addition to de-escalation tactics as part of use of force policy training. More specifically, Longo emphasized UPD's participation in the regional Crisis Intervention Team — or CIT — training with Charlottesville and Albemarle County police since the mid-2000s, when he was CPD chief. CIT training is meant to better equip and educate officers on how to appropriately handle interactions involving individuals who are experiencing “acute episodes of mental illness” or any other crisis situation.

Longo said almost 100 percent of UPD’s patrol force has received CIT training, although he added that he is aiming for the department to review the last time each officer has received a variety of different types of training in the near future to ensure that all personnel are up to date on training requirements.

“Whether you like it or you don't, we're oftentimes the first one to get there [and] we're the first person that gets called so we have to be equipped to at least be able to manage the situation until we can get that person in front of a mental health professional,” Longo said. “Until we do a better job at managing the mental health continuum in this country and ensuring that people who suffer with mental illness have resources that are immediately and readily available to them, I think the reality is that we have to prepare first responders to meet those needs.”

Longo also said that all UPD police officers and security officers — including himself — wear body cameras with sound and video capabilities when on patrol. He added that the department will be implementing new adjustable magnetic body cameras this fall for each officer that also correspond with a camera located inside an officer’s respective vehicle and would be automatically activated whenever the officer’s body camera is activated. The new cameras will also be programmed to constantly record while being worn by an officer so that when an officer does initiate the recording process, the previous 30 seconds of film will also be included in the archived footage, according to Longo.

“So if I got this thing on — and this will be the same with the car camera — and I decide that I'm going to stop a car, I'm going to stop a person or I'm going to get out and engage a citizen about something,” Longo said. “The minute I turn that camera on, that camera will have already recorded 30 seconds before that so …. you'll have an idea of what I was seeing or thinking before I turn this button on.”

Longo added that it is UPD policy and his own expectation that whenever an officer has a “citizen interaction,” their body camera should be activated to capture the interaction, with some exceptions for incidents involving survivors of domestic violence or sexual assault.

With regards to fostering a stronger relationship between UPD and the University community more broadly, Longo said he has already begun discussions on community policing with a number of law enforcement scholars in departments across the University — including the Batten School, the Curry School and the Weldon Cooper Center — and hopes to further leverage the University’s academic resources to devise new models of policing at the University. Although a framework has yet to be formally established for how UPD might go about reforming its relationship with the University community, Longo said he plans to continue the conversations he has already had to unveil a new framework for policing at the University in the near future.

In addition, Longo said that UPD is planning to collaborate with the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, the Office for Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights and the University Counsel to conduct a review of the department’s policies regarding a variety of subject areas — such as bias free policing, use of force guidelines, the investigation of complaints and concerns as well as investigative detention practices. He added that this policy review will take place in conjunction with the annual process of revalidating UPD’s national accreditation with the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, which mandates that accredited agencies follow certain policies and guidelines in order to be eligible.

“So revisiting those policies to make sure that they're not only constitutionally sound, but that they reflect the values of the University and the expectations of our students, faculty, staff and people who come to the University on a regular basis,” Longo said. “And then once we've put eyes on them, take them back to student leadership as well to make sure that those policies reflect the values of the University and the people who live here and work here every day.”

As part of this policy review process, Longo said he looks forward to coordinating with Student Council’s Student Police Advisory Board this fall, adding that the University’s Faculty Senate has expressed an interest in establishing a similar advisory body — which Longo said could potentially be merged with the student advisory board to include the perspective of faculty and staff. The board is currently in the process of considering University administrators to bolster its composition, although no individuals have been formally identified yet.

Lastly, Longo said he is currently working with the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion to create a new position within the police department tasked with increasing diversity in the recruitment and selection of UPD employees, reviewing training guidelines and department policies to ensure compliance with the standards of the office while also engaging with the University and local community in the process.

“There's never been a more important time — in the history of my career at least — to have a meaningful relationship and dialogue with the people that we serve and to think about policing in ways that meet mutual expectations moving forward,” Longo said. “And to have that discussion with students coming back in the fall is really important to me, and I hope this is one of many discussions I’ll be having over the next several weeks.”

In terms of moving forward on police reform and accountability at the University, Publius said he doesn't doubt that individual UPD officers are capable of good actions and carrying out positive interactions with students. However, he added that it is also important to consider the broader history of racism and mistreatment that is a part of policing in the U.S.

“I think that the whole institution of policing in general is built on foundations of exploitation and racism,” he said. “So I'm the type of person who thinks — because the police system is built from these problematic cores — that revamping it or modifying it really won't solve in totality the issues in policing.”

Jacquelyn Kim contributed to this article

This is the fourth article in The Cavalier Daily’s series exploring a list of demands submitted to the University’s racial equity task force on issues of race.

The full series:

- ‘Facing history head-on’: Black student activists submit demands to President Ryan’s racial equity task force

- ‘We don’t want words, we want action’: Black student activists call for ‘a comprehensive culture shift’ at the University

- More Black and POC voices in the room: Black student activists call for Honor and UJC to ‘recommit to efforts of diversity and inclusion’, address how BIPOC students have been ‘disproportionately affected’