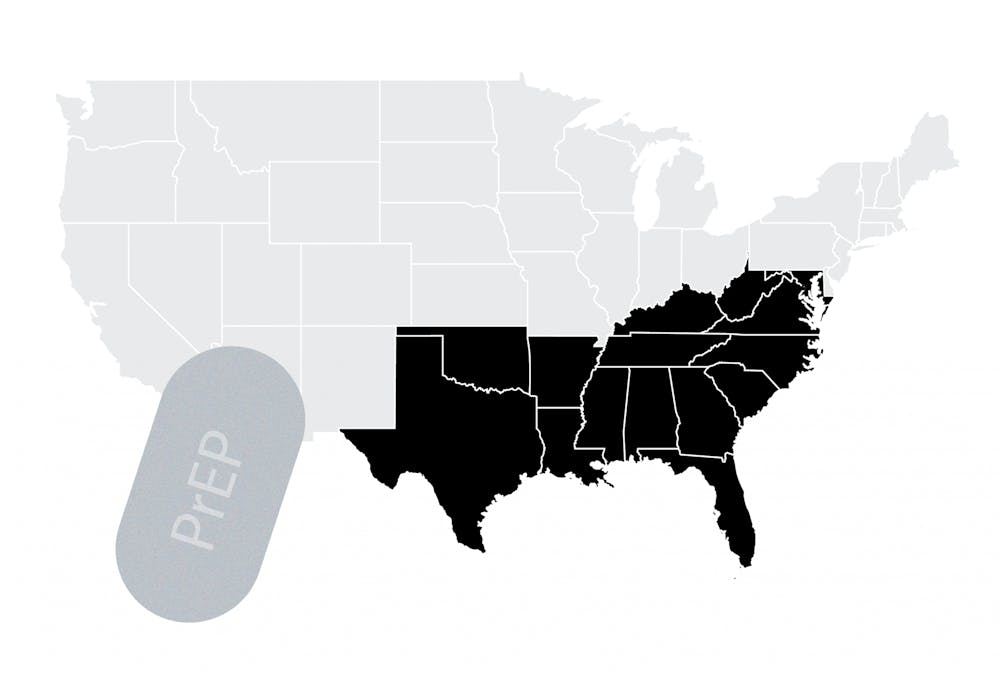

Researchers at the University Health System have recently uncovered a systemic barrier in the South, impacting the access to critical HIV treatment and prevention drug pre-exposure prophylaxis. An insurance requirement known as “prior authorization” has been largely deemed the culprit, researchers reveal. The South is the U.S. region with the highest number of HIV infections each year. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 51 percent of the 37,968 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, throughout the U.S. and depending areas, occurred in the South.

PrEP is a medication for those at high risk of contracting HIV, such as the Black and Latinx populations, to prevent the virus from establishing a permanent infection in the body.

According to the CDC, “studies have shown that PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% when taken daily. Among people who inject drugs, PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV by at least 74% when taken daily.”

Despite the efficacy and importance of this viral preventative treatment, some insurance plans in the South require what is known as “prior authorization,” in which insurance companies have established an additional barrier to care by preventing the immediate approval of the drug. This delay is characterized by additional paperwork for both patients and physicians and a lengthy process of medication approval.

However, prior authorization poses some benefits to insurance companies and possibly consumers.

“From an insurance company's perspective it helps maintain tighter control on what is financed and in many ways it helps balance budgets to some extent, as it is a healthcare market. From a consumer standpoint, if you look at an insurance company website they certainly market it as a benefit to consumers,” said Sam Powers, fourth-year College student conducting infectious disease research at the University.

Another potential benefit of prior authorization is that it poses as a checks and balances mechanism for consumers whose physicians disregard or have no knowledge of potential problematic interactions with other drugs. More expensive medications could also be denied if there is an existence of a cheaper medication. These cost savings could potentially be passed to the consumer.

Kathleen McManus, assistant medicine professor and infectious disease and international health researcher at the University, elaborated more on the concept.

“Insurance companies often say they use prior authorization to ensure that the medication is medically appropriate,” McManus said. “And then if there is more than one medication [for the aliment] sometimes insurance companies use prior authorization to require the patient to start with the less expensive medication.”

According to McManus, however, it is notable that at the time of their study, there was only one HIV-prevention medication. Therefore, insurance companies motives could not have been to try and shift patients to another medication.

Additionally, researchers have uncovered that the rate of prior authorization for insurance plans in the South is significantly higher than those of other regions in the country.

Of the 16,853 qualified health plans that were looked at, with results published in JAMA Network Open, the proportion of qualified health plans in the South which required prior authorization for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis was 37 percent, compared with 13 percent in the Midwest, 6 percent in the West and 2 percent in the Northeast.

When asked why more national health care plans in the South call for prior authorization, McManus said researchers are still trying to figure that out.

“We aren’t sure,” McManus said. “We tried to see if we could explain the use of prior authorization by looking at other plan characteristics to see if a plan uses prior authorization in certain settings. But we could not explain why more health care plans in the South require it. We would think that where there is more HIV you would actually want to see more HIV prevention medication to try to stop and turn things around, that is why we are so concerned to find this.”

Interestingly enough, researchers found that the rate of prior authorization for national insurance companies compared to local plans only offered in the South were comparably much higher. This subtly suggests that local plans in the South are more effective in their care for HIV prevention.

As stated in the research journal, it was concluded that the South is in most dire need of access to PrEP, even though it has lower PrEP use than other regions of the country. Insurance companies' use of prior authorization not only reduces access to care, but according to Sebastian Tello-Trillo, assistant professor of public policy and economics, it plays significantly into the perpetuation of HIV in Black populations and worsens racial disparities that already exist.

“More than 50 percent of African American individuals live in the South, where our research shows they are more likely to face this prior authorization barrier,” Tello-Trillo said.

Tello-Trillo further explained that the lifetime risk of HIV for Black men is 1 in 20, compared to a lifetime risk of 1 in 132 for white men. Additionally, among Black women the lifetime risk is 1 in 48, where among white women it is 1 in 880.

“We can see that Black people in America have higher lifetime risks of contracting HIV because of various structural fractures,” Tello-Trillo said. “And now there is this additional barrier that adds to it.”

Powers further emphasizes the problems prior authorization could pose for those at increased risk of HIV.

“All it takes is one encounter to contract HIV,” Powers said. “So a delay of two weeks ... in getting PrEP could be the difference between people having HIV and not having HIV.”

As someone who works closely with McManus, Powers stated that patients frequently plan on starting PrEP, though contract HIV before they receive the drug.

“It’s always a tragedy when that happens because PrEP could have permanently stopped that from occurring,” Powers said.

A good way to increase access to PrEP and get a tighter grip on the HIV epidemic is to minimize the amount of plans that call for prior authorization for the drug. When asked his opinion on how to achieve this, Tello-Trillo said he believes a couple steps need to be taken.

“I think we need to first … understand the benefits [of prior authorization] and ... think about a standard procedure that either insurers need to follow or that the federal government [has] to follow to allow this insurance to have prior authorization,” Tello-Trillo said.

Finding ways to increase the use and uptake of PrEP in the South is still a problem researchers are attempting to solve.

“If we want more people to use this HIV prevention, we need to make it as easy as possible,” McManus said.