As a part of the Women in Film series of the Virginia Film Festival, director Catherine Gund’s documentary “Aggie” observes her mother’s journey as a philanthropist to examine art as a “means to transform consciousness and inspire social change,” and to highlight the issue of racial injustice. The film was introduced by Matthew McLendon, the director and chief curator at The Fralin Museum of Arts at the University. McLendon presented Agnes — known as “Aggie” — Gund as a “true visionary” in the “quest for our more perfect union.”

Gund’s most famous contribution to the art world and social reform is her selling of Roy Lichtenstein’s “Masterpiece” for a whopping $150 million. After drawing inspiration from Ava DuVernay’s film on mass incarceration titled “13th,” she used the money to start the Art for Justice Fund in order to fight criminal injustice. Some of the fund’s accomplishments include improving education, regaining voter rights for people in Florida and working to end juvenile life without parole. However, the biggest accomplishment of Gund and the Art for Justice Fund is setting a new standard for philanthropy. Aggie’s daughter, Catherine Gund, highlighted the significance of the fund and Aggie’s activism in this documentary by telling her mother’s life story and exploring her journey as an international benefactor.

Gund’s appreciation for art started early. She grew up going to art museums and would attempt to redraw what she saw when she got home. From an early age, Aggie was inspired to “figure out art.” Gund also developed an early connection to social issues with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. When describing her early interactions with racism, Gund explains that it was “easy to say it was other people’s lives or business.” However, she explains that her views changed as she got older, especially with the death of Eric Garner in 2014 at the hands of the police. She recounted that these issues have become much more known to her and the world. She was especially troubled by the death of Trayvon Martin, saying “This could’ve been my family,” as she has biracial grandchildren. These incidents of racial injustice inspired Gund to use her position later in life as President of the Museum of Modern Art to work with underrepresented artists and work towards social reform in many areas.

In her career as an art curator, Gund worked closely with several diverse artists to highlight different perspectives and give rise to divergent voices. In explaining what art she was compelled to present, she asked herself — “Who is underrepresented and under-rewarded?” She formed close relationships with these underrepresented artists to better understand the motivations behind their artwork. John Waters, a filmmaker and close friend of Gund, commented on her relationship with artists, saying they gave her “the confidence to have [her] own confidence.”

Working with a diverse group of artists — such as studio artist Xaviera Simmons, whose work focuses on the representation of Black and white Americans, and portrait photographer Catherine Opie, who praises Aggie’s approach to feminism — is just one of Gund’s many legacies. Discovering new artists who had passions for social change allowed Gund to comment on other cultural issues as well. For example, in her speech at a Case Western graduation ceremony, Gund addressed the fears and concerns surrounding the HIV/AIDs epidemic during the 1970s asserting “These or other cultural treasures are important whether one likes them or not.” Not only does her activism make her “unbelievably iconic,” as portrait photographer Catherine Opie describes, but it makes her a role model for other reformists. DuVernay recalls that Gund made it known that “to be an activist, you are essentially an artist envisioning something that is not yet there but seeing that it can be and will be.” When asked by her grandson what she wants to be remembered for, Gund answered by saying that she wants to be known for “starting things that really put good ideas into people’s minds to do, and that led to good results.”

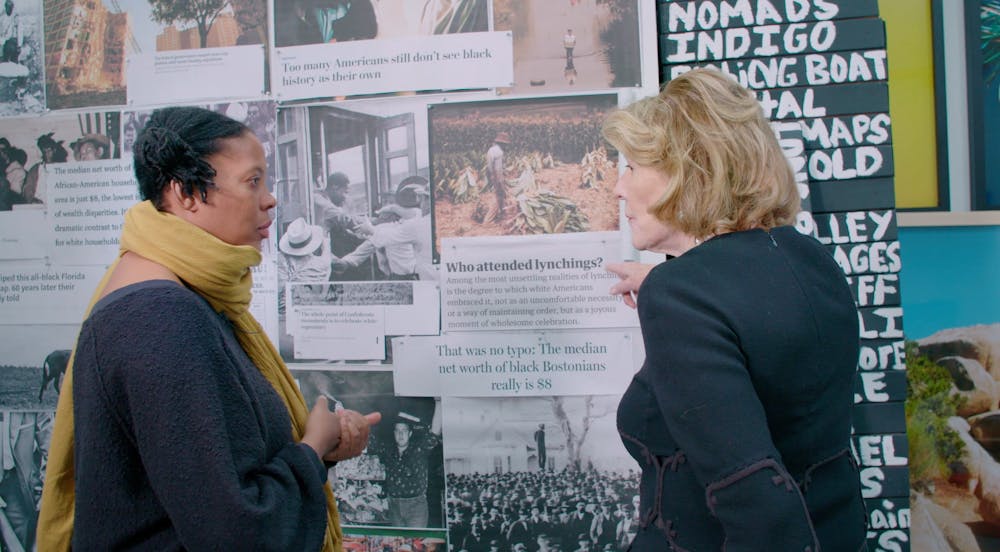

Catherine Gund utilized several effective techniques to tell her mother’s story. One such strategy was the interviews between Aggie and a variety of figures of different backgrounds, races, ages and experiences. Conversing with them further expanded on Aggie’s connection to diversity. Gund also used old videos and photos from Aggie’s early childhood and family life to give viewers insight into her life, just as Aggie sought to gain insight into the lives of the artists she worked with. Finally, Gund illustrated many art pieces curated by Aggie to show that while each had a very different style, they all had a message of modernity and change. Throughout the film, Gund beautifully illustrated the “intersections of art, race, and social justice” in telling her mother’s story. Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, sums up Aggie’s lasting impact in the world by saying that she demonstrated how “art makes it possible for us to have empathy, and without empathy, there is no justice.”