In the 2020 election cycle, multiple science topics — including climate change, vaccine research and mask-wearing — have been heavily politicized.

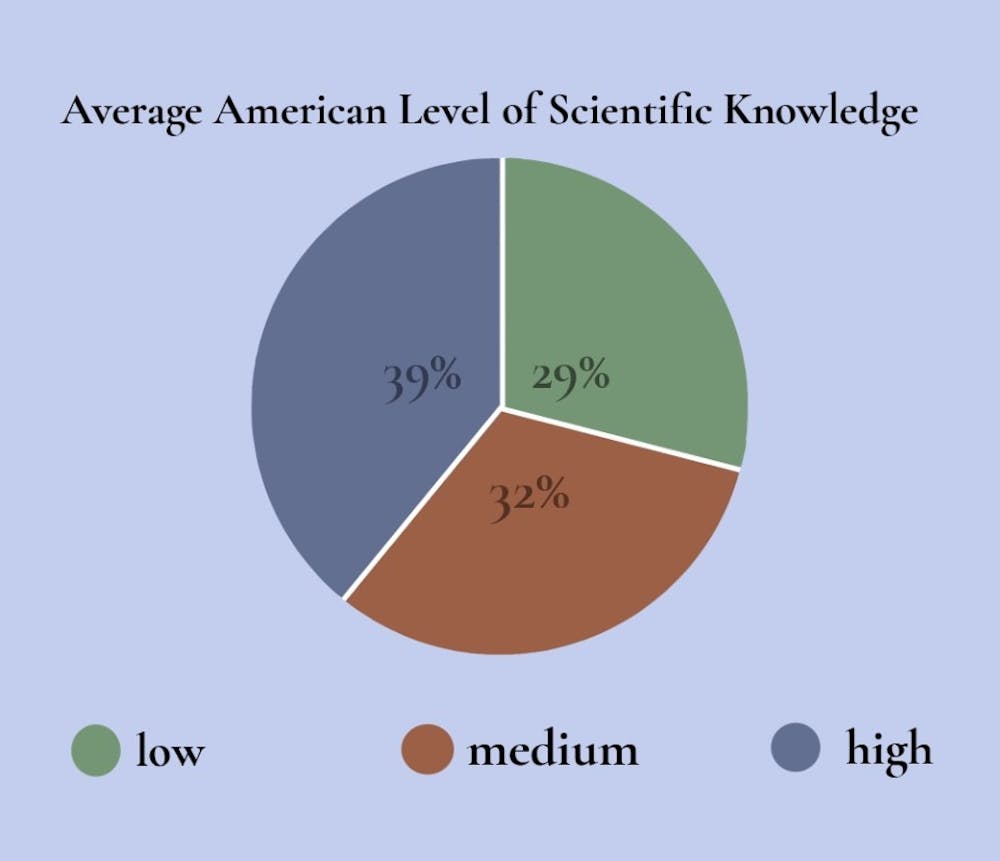

In America today, 39 percent of Americans are classified as having high science knowledge, 32 percent are classified as having medium-level scientific knowledge and 29 percent with low scientific knowledge. These statistics come from a nationally representative science survey from the Pew Research Center, a nonprofit, nonpartisan fact tank and one of the U.S.’s most trusted public polling centers. The questionnaire is made up of 11 basic science questions, such as the cause of Earth’s seasons, what is considered a fossil fuel and the steps present in the scientific process. Those who qualified as highly scientifically literate answered between nine and 11 questions correctly, medium-level literates answered five to eight questions correctly and low literacy was classified as zero to four correct answers.

According to Biology Prof. Sarah Kucenas, these questions do not necessitate complex scientific knowledge, but rather are general concepts that the average American should understand in order to make autonomous decisions about their lives.

For Kucenas, science literacy is the ability to gather information, from sources like Facebook or the news, do homework on that information and then decide to agree or disagree.

“I think what the American people need to do in an election is be able to make a decision for themselves … then vote in a way that you feel mirrors those truths that you decided to gather and that are important to you,” Kucenas said.

Looking back on the history of science literacy, Kucenas says this time period is experiencing the biggest pushback against science that America has ever seen.

“We have people now trying to deny these emergent truths, these things that science has been working towards for decades,” Kucenas said.

Kucenas cites the current U.S. presidential administration’s skepticism of climate change as an example of this pushback.

In a world where information is so easily accessible, Kucenas explains that it is very easy for a person to get the entirety of their information from a single source, making them easy to manipulate.

“If you only get your information from Facebook, you become very quickly controlled by their algorithms,” Kucenas said. “That … takes away the ability of an independent, autonomous human to make a decision.”

Astronomy Prof. Kelsey Johnson also sees science literacy as a fundamental component in life and a foundation for society.

“If people don’t understand basic principles in science, they are fundamentally disenfranchised in the modern world,” Johnson said in an email to The Cavalier Daily.

Johnson describes science literacy as a weapon against confirmation bias — or the tendency for an individual to see new evidence simply as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs and theories — which Johnson feels is at the root of many societal issues. Without an understanding of empirical inquiry, she says, society is left in the dark.

“Science literacy is not about memorizing facts,” Johnson said. “What is far more important is understanding how science proceeds, what counts as evidence and how we establish degrees of confidence in a claim.”

When it comes to becoming scientifically literate, Kucenas stresses that the first thing people need to understand is that they have the tools and autonomy to do so. The biggest hurdle is realizing that everyone has the ability to educate themselves.

In comparison to past elections, Kucenas points out that there is a scarcity in websites that voters can use to understand the stances of political candidates regarding science issues. Reflecting on the 2016 presidential race between then-candidate Donald Trump and Secretary Hillary Clinton, Kucenas says candidate answers to STEM-related questions were readily available.

“What scares me about scientific literacy is I feel like we're being even less open about those things this year,” Kucenas said. “There's not a one-stop shop like there has been in the past to help voters collect that information in a really streamlined way.”

Despite the policalization that has been brought to many science issues, Johnson says that at its core, science is apolitical.

“It is a search for truth and understanding,” Johnson said. “I hope that we can all agree on wanting to know what is true.”