Over the last 125 years, Virginia and Virginia Tech — schools separated by less than 150 miles — have faced each other on the football field 101 times. The in-state rivalry has been full of dramatic games, thrilling storylines and plenty of animosity on both sides.

While most college football fans are well aware of the longstanding rivalry between Virginia and Virginia Tech, they may not be as familiar with the feud’s deep and controversial roots. As the Cavaliers and the Hokies meet for the 102nd time Saturday, let’s take a look at how the over-a-century-old rivalry first started.

Even off the football field, relations between the Virginia and Virginia Tech communities have been tense since the late 1800s. There was a clear divide that existed between the two schools. Virginia was a state university — a historic institution of higher learning — while Virginia Tech — then known as Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College — was a land-grant university that emphasized practical agricultural and engineering education.

“I broke it down into class warfare,” said Roland Lazenby, bestselling sportswriter and co-author of “Hoos 'N' Hokies, the Rivalry: 100 Years of Virginia Tech-Virginia Football.” “ The U.Va. crowd tended to be a lot of sons of bankers and the Virginia Tech crowd tended to be a lot of sons of farmers, and bankers and farmers have never gotten along all that well.”

Lazenby added that the tension between the two institutions also had a geographic component. He explained that those who grew up in the western part of Virginia — in cities like Blacksburg — have “always had an inferiority complex regarding the lowlanders,” including those from Charlottesville.

“Nowhere did a state university have its nose so far in the air, as in Charlottesville,” Lazenby said. “It was Mr. Jefferson's University … In truth, it's just silly stereotypes, but that's the kind of stuff that feeds a fan base, one side looking down at the other.”

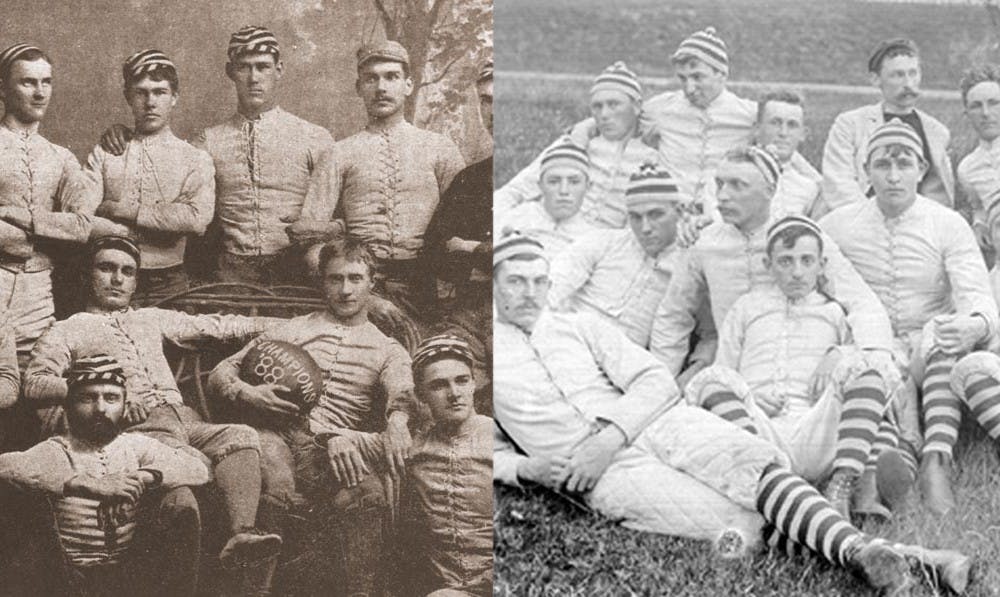

The University of Virginia (left) played its first official football game in 1888, while Virginia Tech (right) played its first game in 1892. Photos courtesy Virginia Magazine and Wikimedia Commons.

But Virginia and Virginia Tech’s football teams are more closely connected than one might think. The two teams were established within four years of each other — Virginia played its first intercollegiate game in 1888, while Virginia Tech took the field for the first time in 1892.

Interestingly, many University graduates, including W.E. Anderson, Joseph Massie and Arlie Jones, played significant roles in the emergence of college football in Blacksburg. Anderson — who was simultaneously a professor and player for Virginia Tech — helped start the Hokies’ football program, while Massie and Jones both coached the team in the mid-1890s. According to Kevin Edds, writer and director of “Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football,” “the birth of Hokie Nation was started by Wahoos.”

For years, there was little antagonism between the two teams. Virginia — the most dominant football team in the South at the time — comfortably won its first eight games against Virginia Tech from 1895 to 1904 by a combined score of 175-5. However, the rivalry quickly heated up largely due to one driven Virginia Tech player — Hunter Carpenter.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Carpenter was an iconic college football halfback who was named to the All-Southern team three times and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1957. To say Carpenter’s career was unique would be an understatement. Carpenter enrolled at Virginia Tech in 1898 and competed on the football team from 1899 to 1903 — three seasons as an undergraduate, one as a graduate and one more as a faculty member.

Despite his talent and the fact that he played five seasons in six years in Blacksburg, Carpenter was not able to defeat Virginia. Desperate for a win against the Cavaliers, Carpenter enrolled at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill as a law student and joined the school’s successful football team. At the time of the move, Carpenter said, “I just want to beat the University of Virginia,” according to the Associated Press. In spite of his best efforts, Carpenter once again failed to beat Virginia in 1904 — this time as a Tar Heel.

“After losing again, when a U.Va. extra point ricocheted off a player’s head up through the goalpost for a one-point U.Va. win over North Carolina, Carpenter was devastated,” Edds said. “U.Va. was his white whale. So [Captain] Ahab went back to his original ship for one more hunting season.”

At this point, it appeared Carpenter’s dreams of taking down Virginia were crushed. However, in unprecedented fashion, Carpenter decided to return to Virginia Tech in 1905 for his seventh season as a college football player.

Carpenter’s controversial homecoming was not well-received by Virginia. The University’s students, administrators and supporters were becoming increasingly frustrated with their opponents’ disregard for the sanctity of student-athlete eligibility. In Virginia’s eyes, Carpenter — on the verge of playing for nearly a decade — epitomized an issue plaguing amateur sports.

Soon enough, in the leadup to the 1905 Virginia-Virginia Tech game, relations between the two sides turned ugly. College Topics — the original name of The Cavalier Daily — alleged that Carpenter was being paid to play, and Carpenter responded by threatening to sue the student newspaper for libel.

University students, who ran the athletics department, even considered canceling the game altogether. But, after the University’s entire student body convened at Madison Hall and voted on the matter, Virginia decided to play Virginia Tech so as to not disappoint the fanbase.

“To put it bluntly, [the catalyst for the rivalry] was Virginia Tech’s reluctance to play by established eligibility rules,” Edds said.

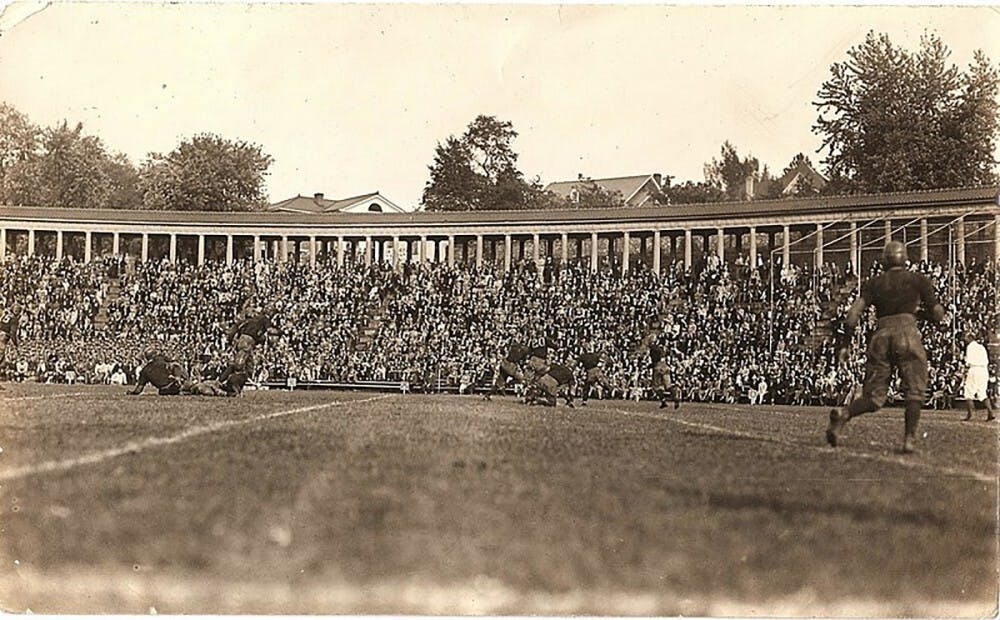

After going as far as signing an affidavit, denying accusations of being compensated, Carpenter was allowed to compete in the game, which was held at Lambeth Field in Charlottesville Nov. 4, 1905. Unfortunately, Virginia fans at the time not only witnessed Carpenter take the field for the seventh time against them, but also saw him lead Virginia Tech to a historic victory over its in-state rival. The game, which only ended due to darkness, finished with a scoreline of 11-0 in Virginia Tech’s favor.

“Virginia Tech won the game, even though Carpenter was ejected for punching a U.Va. player — perhaps in retaliation — and then threw the football into the stands at Lambeth Field,” Edds said. “The uproar in Blacksburg over Tech’s first-ever win in the series was enough for U.Va. to discontinue the rivalry for 17 seasons.”

In addition to the Carpenter situation, Edds said Virginia Tech added insult to injury when its student yearbook, The Bugle, printed a caricature of U.Va. Athletics Director William Lambeth preaching ‘Pure Athletics’ while handing a $100 bill to a football player behind his back.

“That insult to Lambeth’s honor, after Virginia Tech was the team guilty of having an ineligible player, was most likely the final straw,” Edds added.

Virginia and Virginia Tech would not play again until 1923. It was by far the longest intermission ever between the two football teams. The almost two-decade gap in the rivalry was a direct result of Virginia’s anger towards Virginia Tech finally boiling over after years of tension.

“It went on so long, people forgot why they didn't like each other,” Lazenby said. “They didn't even remember what happened, but they just knew they weren't going to play.”

In many ways, Carpenter may just be the most influential character in the Cavaliers and Hokies’ long, interconnected story. His actions drove a permanent wedge between Virginia and Virginia Tech, one that still exists in the present day — more than a century later. While Carpenter’s name may not be universally known today, generations of Virginia and Virginia Tech fans learned to dislike each other because of beliefs that originated from that fateful 1905 game.

Photo courtesy Virginia Athletics

Since the rivalry resumed in 1923, Virginia and Virginia Tech have played 92 times. During this stretch of history, countless coaches, players and fans have come and gone. However, one element of the rivalry remains constant — each side’s unwavering desire to beat the other, an emotion originally felt by Carpenter 120 years ago.

“There's no shortage of insults the two sides could toss back and forth,” Lazenby said. “Fortunately, it's not like politics. In politics today, we're really arguing to the point of genuine hate. With U.Va. and Tech, they still love each other.”