Historian Andrew M. Davenport, artist Jabari C. Jefferson and activist Myra Anderson joined Monticello’s Getting Word African American Oral History Project on Saturday for a discussion on their shared mission to build a more racially and socially just world. The speakers are connected through their ancestors, and all were descended from Monticello’s enslaved families. They shared their experiences learning about their roots, their current activist work, and answered questions from the audience.

Leslie Bowman, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, introduced the event — aptly titled “Young Voices Rising” — calling Monticello “the epicenter for conversations about freedom and enslavement, equality and inequality, justice and injustice.”

With participation from over 200 descendants, Monticello’s Getting Word Project seeks to “explore the resilience exemplified by the enslaved community and their descendants” as well as preserve their histories. The project started in 1993, and over 100 interviews have been conducted with descendants of enslaved Monticello families.

The three speakers represent a new generation of activists who are passionate about the arts and politics, active in their communities and who share a commitment to racial and social justice.

Davenport, a current doctoral student in U.S. History at Georgetown University and descendant of the enslaved Hemings and Hubbard families, moderated the event.

Conducting research and working with the Getting Word project has taught Davenport “how writing and interpreting African American history is the work of many hands.”

Jefferson is a mixed media oil painter from Washington D.C. who hopes to illustrate “what the process of learning looks like” through his artwork. Jabari Jefferson is a descendant of the enslaved Granger, Hemings and Evans families of Monticello.

Anderson is a social entrepreneur, mental health and social justice advocate and a current community fellow at the Equity Center at the University. Anderson recently learned that she is a descendant of the enslaved Hern families at Monticello.

When Anderson’s grandmother first told her about the family’s enslaved ancestors, Anderson didn’t believe her. Her history textbooks made no mention of Thomas Jefferson owning slaves. It wasn’t until Anderson spoke to Niya Bates, a historian working with the Getting Word Project in Virginia, that Anderson could verify her grandmother’s testimony.

“Here I am 5,000 miles from home, making this connection, which had a profound impact on my life moving forward,” Anderson said. “In learning more about them, it’s been like taking a deep breath, and the only way to exhale is to keep learning more.”

When asked how her knowledge of Black history has influenced her activism in Charlottesville, Anderson spoke about how she felt that her activism was “embedded in her DNA.” While her ancestors were alive when Jefferson penned promises of freedoms upon which America was founded, they were excluded from its rewards.

“The omission of my ancestors has me fighting seven years later for freedoms … freedom to be in certain places, and the freedom not to be stereotyped,” Anderson said.

When Anderson sees injustice, she is driven to action and feels “called to be a voice” for those who came before her and weren’t able to speak out against these injustices. Her experience of Black history, however, is one not exclusive to the past, but is a lived experience.

“I experience Black history every day and so has every generation before me — historical events have modern-day legacies,” Anderson said. “I am Black history.”

Telling their ancestors’ stories allows Anderson, Jefferson and other descendants to work to build a more equitable society by giving a more complete and transparent account of the past. Both Anderson and Jefferson shared the ancestors they would most like to meet, speaking of connections they felt to these people of their pasts.

Anderson would want to meet her sixth-generation great aunt, Edith Hurn Fossett, who was the head chef at Monticello for the final 17 years of Thomas Jefferson’s life. Anderson would appreciate the opportunity to “understand how, despite all of adversity, Edith was able to accomplish so much.”

Jabari Jefferson represents the fourth generation in his family to participate in the Getting Words project. His father and grandfather, both historians, provided a “fountain of knowledge” to him that indulged his thirst for understanding.

If he could meet one of his ancestors, Jefferson would want to meet Jupiter Jefferson, who was responsible for keeping the stables and tending Thomas Jefferson’s horses. Jupiter Jefferson was also a talented stone mason who crafted the entrance to Monticello, and later, his entrepreneurial spirit led him to launch his own business working with metal and eventually he lent support to Thomas Jefferson in his old age.

Jabari Jefferson said that since childhood, he felt a connection to horses and was later able to understand that this unique affinity was actually connected to his ancestors. Davenport noted in response that Jabri Jefferson is living proof of the truth that “knowledge of history informs your own talents.”

“History is inscribed in you,” Davenport said.

Jabari Jefferson plans to name one of his children Jupiter to commemorate his legacy. Until then, he uses art as a medium to keep his ancestors’ legacies alive.

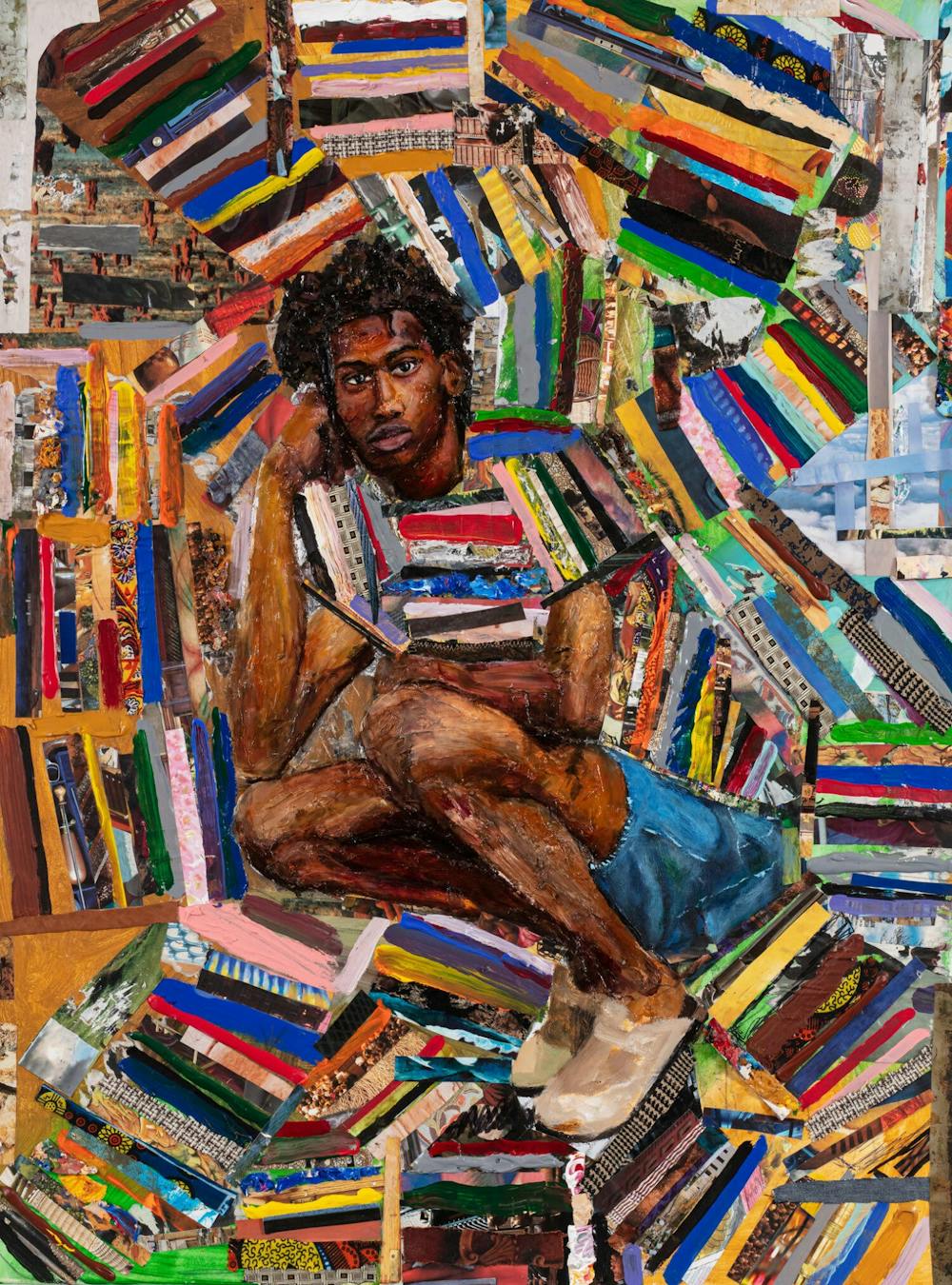

Jabari Jefferson described for the audience a couple of his works, all of which are marked by a powerful combination of mediums and messages.

His piece “Trust the Process,” a mixed media piece done on canvas, “represents the form of patience and faith.” In his words, the painting is supposed to communicate the message that “there’s a lot of nuance in the journey of betterment.”

During the Zoom event, Jabari Jefferson sat in front of a wall displaying one of his own works of art, “And Then There Was I.” The piece, which was inspired by his father and grandfather, reflects the “internal feeling of pursuing knowledge of the self and the environment around you. It captures the intimate moments when you realize you’re talking to the right ancestor and that your journey is about to begin.”

One audience member posed a question about the most important ways to become an anti-racist.

According to Anderson, we must “acknowledge that we all have some racist tendencies and then make a commitment to become aware of that, and educate oneself.” This undertaking requires “humility and understanding,” as it requires one to reflect on one’s own attitudes and ideas and then make an active effort to learn.

Jabari Jefferson spoke about the need to educate oneself and one’s family about African American history as an individual pursuit, rather than just an institutional one. He shared that as a child, he was taught to use the term “enslaved people” instead of “slaves.” By striving for historical accuracy in his art instead of solely aesthetics, Jabari Jefferson is able to more honestly tell the stories of his enslaved ancestors.

All three panelists spoke about the project being a collaborative effort, with Davenport articulating that each descendant adds their “own threads of connection.”

In closing the event, Davenport called on audience members to “strive toward a more democratic present and future.”