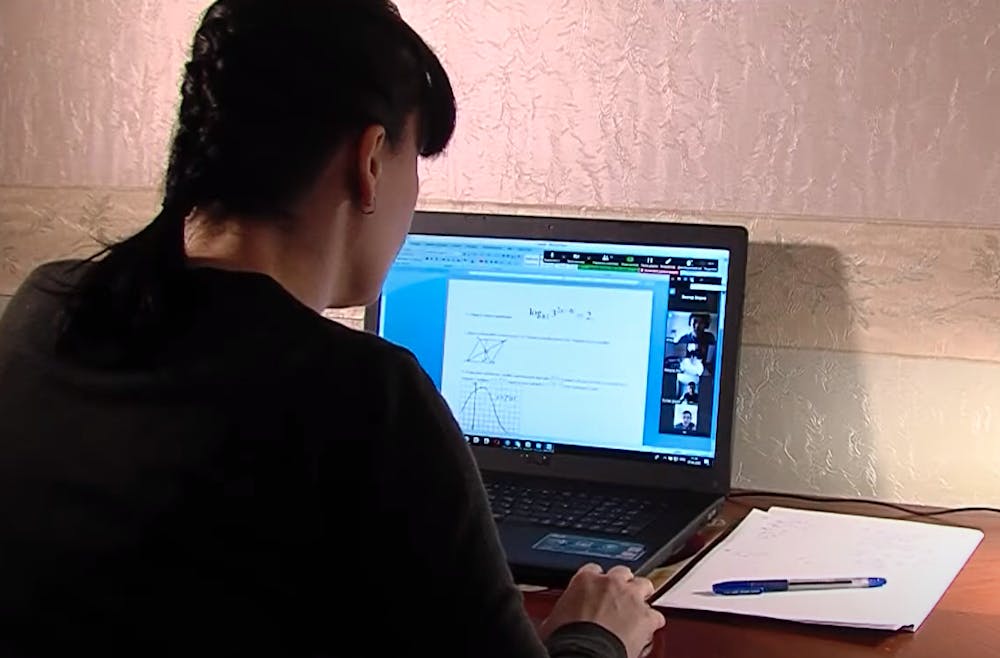

This fall semester, I virtually mentored 8th grade students at Albemarle County’s Walton Middle School through a non-profit organization called Rise Together. The experience was incredibly rewarding, inspiring and eye-opening. Every Monday and Wednesday, I would join a Zoom meeting with Advancement Via Individual Determination students — a program that supports students in preparing for college by teaching them important skills through social-emotional learning and tutoring. However, as the weeks wore on, I noticed that the pandemic was taking a toll on the students and their learning. They were studying and attending online classes from their homes, where distractions were rampant and educational support scarce. While Walton Middle School and Albemarle County Public Schools supported their students in every way they could, the pandemic challenged students in ways beyond the reach of the school system. My experiences mentoring students this fall revealed a country that struggled to support their most vulnerable students due to the inherent challenges in remote learning.

The 8th grade AVID program at Walton was a small class, and we provided as much personalized attention as we could. Unfortunately, truancy increased and motivation declined over the semester. The middle schoolers did not have the stronger infrastructure that attending in-person school provided, leading many to skip assignments, skip class or switch to asynchronous sessions if they felt overwhelmed. I wish that Albemarle County had more resources to better support these students who wanted to learn and participate, but simply had circumstances at home that were less than conducive for learning. I recently struggled to complete college finals in a home with my parents and siblings also working remotely and I can’t imagine how distracting and difficult online school must be for these 8th graders.

School buildings provide resources that the most vulnerable students need, such as a language immersion environment for English language learners as well as specialized instruction and care for students with disabilities. Fairfax County — the largest public school district in Virginia — recently reported 11 percent of their students were failing at least two classes, up from six percent this time last year. The pandemic’s toll isn’t just academic either — student mental health is suffering and distance learning places additional stress on families who may need to work during the day.

Educational institutions, even with limited resources, can adjust to the circumstances of the pandemic to address and close some of these learning gaps. The most effective path is for individual educators to understand each students’ individual learning challenges and be flexible with their needs. For example, some students prefer to have their camera off because of their living situation, and some kids might need more time to complete assignments due to spotty WiFi at home or needing to help with siblings or chores. These accommodations can be easily implemented by teachers, who need simple, concrete solutions that don’t add to the burnout and stress they shoulder from a lack of technological and instructional support in this new virtual setting. It is also especially important to earn students’ trust, who may feel as though they have no support otherwise. I noticed that when mentors took the time to get to know students personally, they became more comfortable with the mentors and the overall environment became more productive and fun.

Schools’ emphasis should be on mastery of content, rather than letter grades. This will ensure that students are not unnecessarily pressured during these difficult times. A recent study by the Rand Corporation reported that less than 60 percent of primary and secondary school teachers assigned letter grades in the fall. Abandoning letter grades is a practice that should be adopted by most school districts during the pandemic because it would ease the pressure on students to perform. Many high schoolers, in particular, are still under the pressure of a perfect transcript, whether that be from parents, colleges, or themselves. In elementary and middle schools, in-depth feedback rather than letter grades would help target kids’ weak points and provide room for growth. The pandemic provides too many challenges outside of a child’s control — unstable internet connections, a lack of additional academic support, and home environments that may not be conducive to learning. The study also revealed that students are less prepared for work at their grade level, and with the pandemic, tutoring and support is limited. K-12 students should be released from the pressure of grades until their districts have made stable plans to get them back on track.

Schools can address pandemic challenges through additional communication with students and their families as well as increased understanding and leeway with their needs. While I was happy to mentor through Rise Together alongside the incredible staff at Walton Elementary School, my experiences revealed issues that need to be addressed in the age of COVID in order to best meet the needs of students.

Nicole Chebili is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.