Just over a year after the first COVID-19 case was documented in Wuhan, China, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized two vaccines for emergency use against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The first, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, was authorized on Dec. 11, 2020, and just a week later, the FDA authorized the Moderna vaccine. These authorizations came after months of phase 3 clinical trials with a diverse group of participants — Pfizer enrolled 43,448 participants in their trial while Moderna enrolled 30,000 participants. These vaccines will play a critical role in ending the pandemic and allow life to regain a sense of normalcy.

William Petri, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health at U.Va., notes that the vaccine trials were conducted with a broad range of test subjects, giving scientists greater reassurance about the trials’ positive results.

“They made a pretty good attempt to include a fair representation of people with underlying medical illnesses, the elderly, the African-American and Latinx communities,” Petri said. “These vaccines are amazingly effective, and they are effective in people with underlying illnesses and in the elderly, which is, of course, who we want to protect the most.”

According to the Virginia Department of Health, 1,156,117 total COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in Virginia. Approximately 10 percent of the state’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and an average of 33,520 doses are administered each day. In Virginia, populations 70 years or older make up 27 percent of those who have received one dose of the vaccine. Additionally, of the 66 percent of vaccinations that report the race or ethnicity of the recipient, 28 percent have gone to people of color.

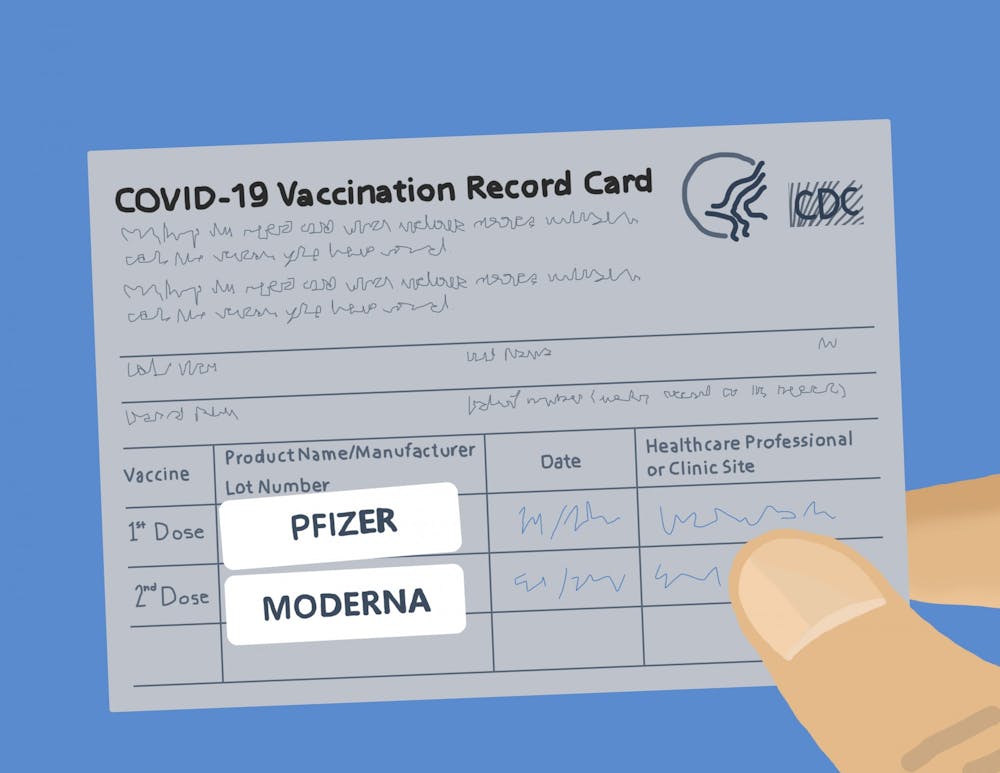

The CDC stated that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is 95 percent effective in preventing symptomatic infection in individuals ages 16 years and older while the Moderna vaccine is 94.1 percent effective for individuals ages 18 years and older. The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines both require a “booster,” or follow-up, vaccine three and four weeks, respectively, after the initial dose.

“The first dose primes the immune system and the second dose boosts it,” Petri said. “In the case of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, the second dose increases the protection afforded by the vaccine from 60 percent to approximately 95 percent … mRNA vaccines are uniquely capable of inducing a kind of an immune cell, called a T follicular helper cell, to help B cells produce antibodies. It is this help in antibody production that makes these vaccines so effective.”

Both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines use messenger RNA, known as mRNA, a genetic element naturally present in the human body. Dr. Costi Sifri, director of hospital epidemiology at the University, explained that mRNA provides a template for making proteins. Once injected into the body, the mRNA instructs cells to create spike, or S, glycoproteins. Then, the body detects the synthesized proteins and creates an immune response against them.

“This protein itself is a part of SARS-CoV-2,” Sifri said. “That’s the Achilles’ heel. It’s a key component used by the virus to cause disease … and the central target for all vaccines that are currently being either used or in the late stages of development.”

Sifri further explained that S glycoproteins are an essential part of SARS-CoV-2 because they allow the virus to attach itself to healthy cells. Allowing the body to prepare an immune response against the S glycoproteins prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection largely prevents future symptomatic infection.

“By developing an immune response to this key protein … you've allowed the body to learn how to protect itself from the virus,” Sifri said.

While it is still largely unknown how long the vaccines protect against symptomatic infection of SARS-CoV-2 — partially as a result of insufficient data thus far — both Petri and Sifri are hopeful that it will be long lasting. However, it is possible that vaccinated people can still contribute to the asymptomatic spread of COVID-19.

Wendy Armstrong — an Emory University professor of medicine and the vice chair of education and integration for the school’s Department of Medicine — explained that while it is certain the vaccines prevent symptomatic transmission of COVID-19, it is not yet known if the vaccines prevent asymptomatic transmission as well.

“One of those unknowns is whether or not a vaccinated person can get an asymptomatic viral infection that they could then spread to someone else,” Armstrong said. “I think there is some reassuring data that may not occur, but we do not know for sure.”

Part of this reassurance stems from the fact that, in the Moderna study, participants were tested for COVID-19 before receiving each dose of the vaccine. When comparing those who received the vaccine to those in the placebo group, there were fewer asymptomatic infections among the vaccine group. However, further data is needed to confirm any hypothesis.

Because asymptomatic transmission is still a possibility, Armstrong recommends continuing to practice COVID-19 safety precautions, including social distancing and handwashing, even after vaccination.

While these vaccines are nothing short of revolutionary, challenges have plagued their distribution. For instance, both vaccines must be stored at ultra-cold temperatures, and some facilities, especially in rural areas, do not have the resources to store them.

“The Pfizer vaccine requires a deep freezer,” Sifri said. “They're shipped on dry ice and they're stored in these deep freezers that have a temperature of -70 to -80 degrees Celsius. In contrast, the Moderna vaccine is manufactured and stored in -20 degrees Celsius.”

Armstrong explained another challenge facing vaccine distribution — some people are not comfortable receiving these vaccines. She suspected that the name of the U.S. government initiative to develop COVID-19 vaccines, Operation Warp Speed, misled the public to believe vaccines were developed too quickly and without proper testing and precautions.

“That isn’t true — what Operation Warp Speed essentially did was it allowed the federal government to pour billions of dollars into this effort, allowing the process to move along more quickly,” Armstrong said. “We try and encourage and reassure people that all the safety checks have been done … that the trials have enrolled and tested the usual number of patients and that there's been no cutting corners.”

In order to receive FDA approval, both the Moderna and Pfizer had to meet the strict standards laid out in the FDA’s Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19 guidelines. These included randomization of vaccine distribution, follow-up studies on participants and close tracking of any adverse effects after vaccination, among others.

Armstrong also discussed the rise of SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the British and South African variants. Another variant has also recently been identified in Brazil. There are two reported cases of the United Kingdom variant in Virginia as of Jan. 31.

The CDC states that these variants are more transmissible and can spread more quickly, increasing the amount of COVID-19 cases. Armstrong explained that while both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccine are effective against the British variant, both vaccines provide slightly less protection against the South African variant. To combat new strains of the virus, both Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna plan to develop additional booster shots for better protection.

Armstrong stressed the importance of getting vaccinated, especially with the recent emergence of new variants.

“I believe it's really, really important to get vaccinated, and I think until we have a mostly vaccinated population, we're going to be struggling with coronavirus for a long time,” Armstrong said.