Lea en español

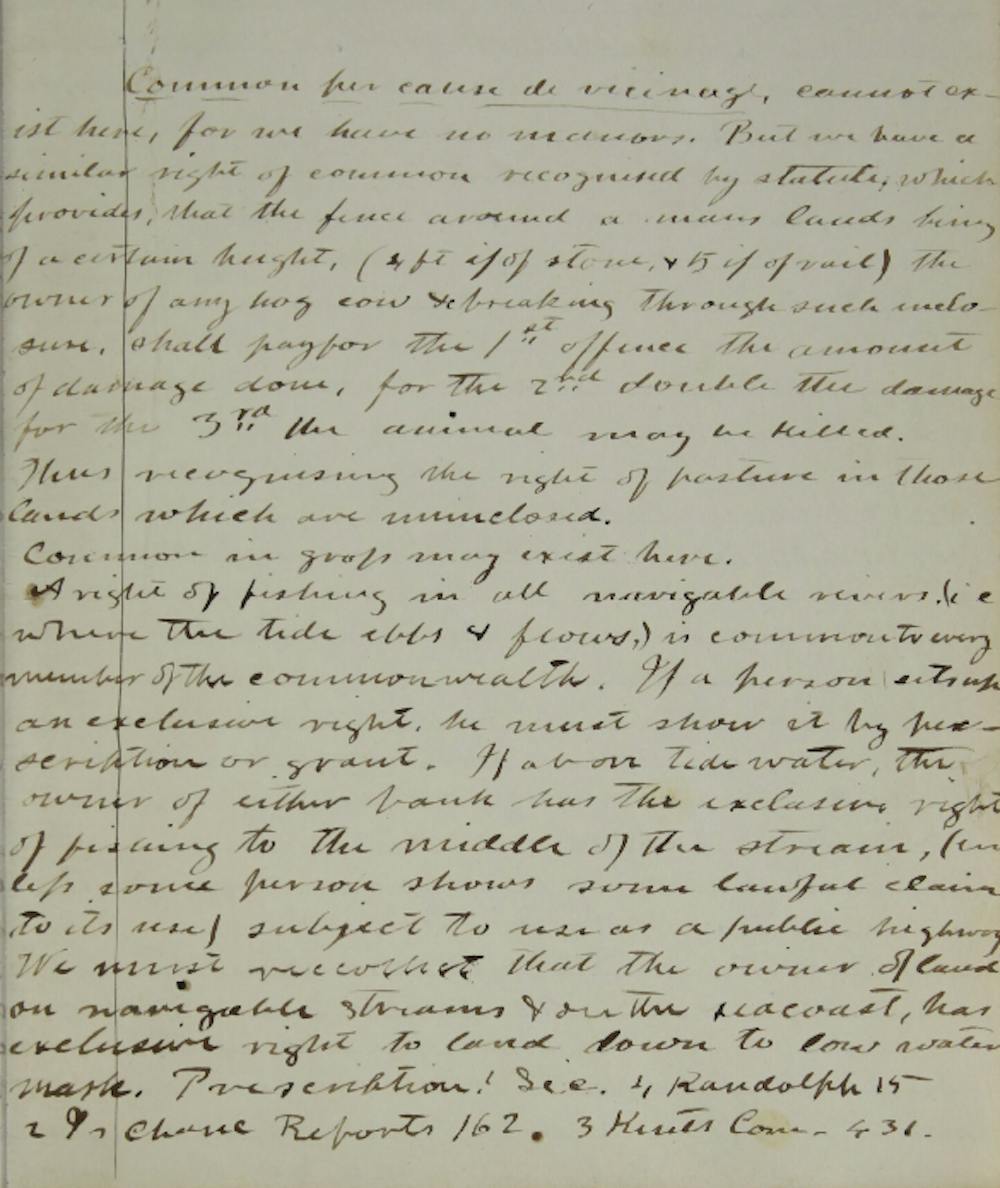

The University’s Law school launched Slavery and the U.Va. School of Law — a new website and digital archive that explores the law school's historical connections to slavery — on Feb 1. At the core of this project are digitized versions of law students’ notebooks from the antebellum time period, when slavery was taught as a social good.

The idea for the project emerged in 2017, according to Randi Flaherty, Special Collections librarian at the Law School, after she attended a symposium by the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.

“The project was inspired by the work of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University at U.Va. by calls to action within the Law School community to address this history and by the general importance of shedding light on the history of enslavement and enslaved people at the University,” Flaherty said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “We felt that there was a space that we could fill in supporting research into slavery as it was taught in the U.Va. classroom.”

According to Flaherty, the development of this website was a team effort. She started the project and helped guide the research while Loren Moulds, head of digital scholarship at the Law School, built the site and Logan Heiman, Law School communication specialist, managed the project operations when he joined the team in 2019. Flaherty pointed out that there were a number of others who contributed to the project through providing research, preserving and scanning the notebooks and offering feedback.

The new website features student notes that are also currently held at the University’s Law Library and demonstrate the transformation of the legal curriculum over time. According to the website, these notes largely focus on legal theory and display how the Law School faculty and students learned and applied the law to bear upon questions of property, contracts and slavery

The notes also showed that it was rare for an entire lecture to be dedicated to enslavement — rather, it was more common for students to learn about slavery and enslaved people through discussions on property law and the U.S. Constitution, by which professors would bring up the laws of slavery and their theoretical interpretations of slavery.

Ultimately, the students’ notes revealed that the Law School supplied students of the antebellum period with legal justifications for slavery.

Moreover, the website features the profiles of people and places with a meaningful connection to the Law School during the time period. This included enslaved people, professors and buildings on Grounds.

The website features the key profile of Lewis Commodore, who was the only person known to be directly enslaved by the University. According to the website, Commodore served as a Rotunda bell ringer and janitor before a group of faculty members, including Law Professor John A.G. Davis, purchased him for 580 dollars. These professors were later reimbursed by the Board of Visitors.

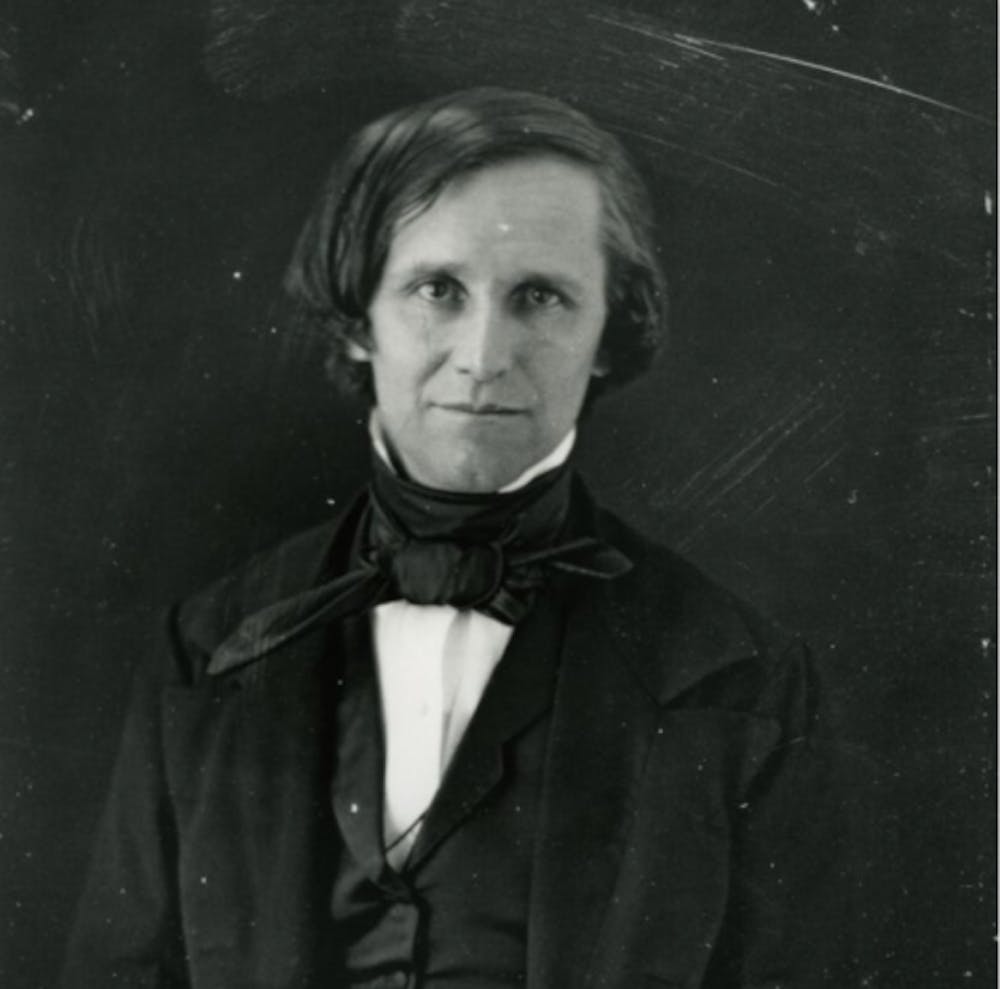

Additionally, the website spotlights the profile of John B. Minor, who became a law professor in 1845 and taught for 50 years before retiring shortly before his death. Minor became a prominent legal scholar in the South who was unsure of the constitutionality of secession but thought it was important to protect the South’s institutions, which included slavery. Minor Hall, which is located on Central Grounds, is named after Minor and became the Law School building in 1911.

Flaherty pointed out that given that the Law School is currently located on North Grounds, many forget that the Law School was actually located on Main Grounds during its first 150 years of existence.

The website also discusses the Sunnyside property, which is where the Law School currently sits. During the 19th century, several families lived on this land which was farmed by enslaved people. According to Flaherty, this land was originally occupied by the Monocan nation and then purchased by the Duke Family in 1863.

“We know that wheat, fruit, hay, sugar and corn grew here,” Flaherty said. “We know the names of some of the enslaved people who lived and labored here. We also know that the Duke property — back along the current Rivanna trail, behind the Law and Business schools — was used after the Civil War as a site for large and well-known barbecues in Charlottesville during U.Va. reunions and for the Cool Spring Barbecue Club.”

The Cool Spring Barbeque Club, like other barbecues, was an event hosted by Col. R. T. W. Duke, Sr., where dignitaries across the state would gather to build connections with each other while eating squirrel stew, pork barbecue and whiskey, among other things. According to Flaherty, one of the chefs at these events was Caesar Young, who had once been enslaved on the Sunnyside property and later became well known in the area for his barbecue food.

In a statement to The Cavalier Daily, Moulds noted that this website serves as an opportunity for the community to engage seriously with the University’s history that has been “largely avoided, forgotten or remained undiscovered.”

“If we wish to address injustice and work towards both racial equality and a more complete understanding of the past, we can no longer avoid or hide from regrettable parts of our history,” Moulds said. “In short, efforts like this help us answer important questions about the context in which decisions were made or conditions experienced by students, staff, and faculty, including how buildings were named, who was hired, what was taught, who lived where or how alumni used their education in their professional careers.”

Heiman added that the Law School has a history of producing lawyers and public servants and is an institution that is now committed to justice and the public good.

“Contending with the law school’s contributions to slavery, particularly its intellectual contributions, is an important step in the process of holding the Law School accountable to its professed values and mission,” Heiman said. “We hope that by studying the history this website makes available, both the students and faculty of U.Va. Law and the wider community can work together to build a future based on a clear-eyed understanding of the ways this law school has contributed to justice and injustice in its past.”

In another section of the website, there are a series of essays written by members of the Law Library. Additionally, there are published pieces authored by graduate students and faculty who are associated with similar projects such as Jefferson’s University … the Early Life. JUEL is a website that consists of a variety of resources and information about the beginnings of the University.

According to the Law School’s new website, scholars and researchers using the resources on the website are welcome to publish their preliminary work on slavery and its connection to the University there.

“As we proceed with this research, we have been collaborating with a group from the JUEL project to share research and help tell this history, particularly as it relates to the history of slavery and race at Pavilion X,” Flaherty said.

According to the project collaborators, more research will continue to be added in order to keep the website alive. Moulds noted that they hope to continue adding “interpretive content and archival materials.” Moulds added that the team hopes to “leverage the online components of this project” with their upcoming project about the history of the legal curriculum at the Law School in an edited volume of U.Va. Press. Additionally, Flaherty stated that there is more work to be done to “identify and spotlight the lives of enslaved people.”

“As researchers dig into the student notebooks, we want to make accessible new findings on how slavery was taught and discussed in the classroom through essays or blog posts,” Flaherty said. “The Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library on U.Va. Main Grounds has a tremendous collection of these law student notebooks, and we would love to explore a collaboration with them in the future to digitize these materials.”