In 2016, a petition written by Charlottesville student activist and second-year College student Zyahna Bryant voiced the discomfort felt by Black residents because of the city’s Confederate monuments. In 2017, the City Council voted to permit removing the statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, although the ruling was barred by permanent injunction in Oct. 2019 after local residents filed a lawsuit against their removal in Mar. 2017.

In 2018, Assoc. Religious Studies Prof. Jalane Schmidt and Andrea Douglas, executive director of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center and former University professor, introduced their Marked by These Monuments tour to serve as a way to educate and inform locals and visitors alike about the history of Charlottesville’s Confederate monuments. As of Feb. 11, the virtual tour has had over 8,545 visitors and over 17,225 page views since its publication in Aug. 2019.

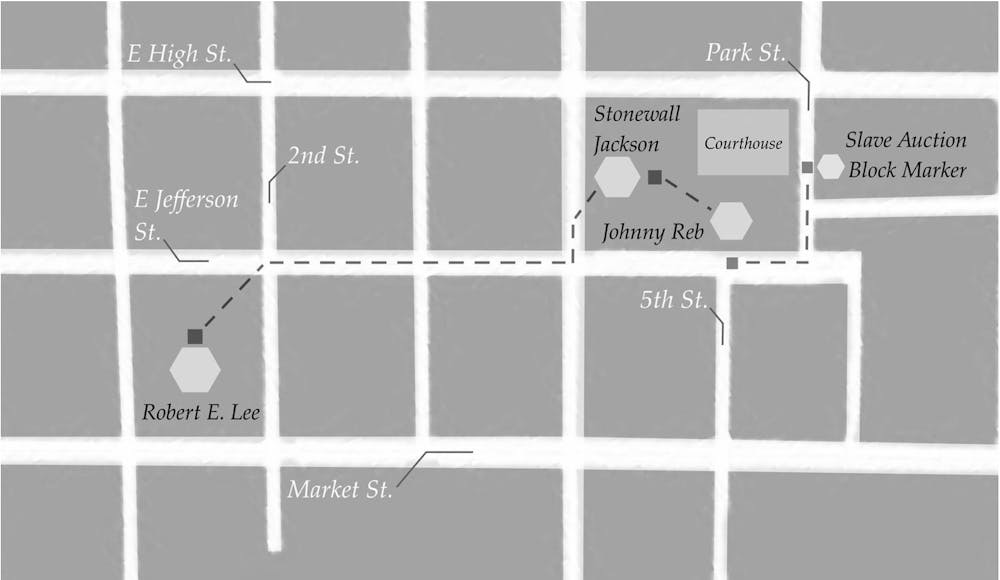

Both the in-person and the online version of the tour begin in downtown Charlottesville at the Slave Auction Block Marker situated next to the Courthouse. Consistent with chronological order, the tour begins by discussing Charlottesville’s social environment during the pre-Civil War era. The tour continues by using reference points that include Charlottesville’s Confederate monuments to cover the historical periods that follow and provide context for the underlying racism that is scattered throughout.

"[We] want to push back against the notion that these are innocent," Schmidt said. "They are not. We often bring up the example there are no monuments to the glorious Third Reich in today's Germany. How we want to represent our values and public space is what we're talking about here. What values are we going to broadcast on a daily basis from our publicly maintained public spaces?"

The virtual tour in particular highlights four Charlottesville Confederate markers and monuments, some of which have been physically removed since the tour’s inception. The Slave Auction Block Marker, stolen Feb. 2020 by a local activist, has since been returned to Charlottesville officials who are yet to make a decision regarding the plaque’s right to return to the Court Square. The Johnny Reb statue, also known as “At Ready,” was removed Sept. 2020 from the Albemarle County Circuit Courthouse lawn. The state statute that was used to validate a permanent injunction against the removal of the Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee statues is currently in contention at the Virginia Supreme Court as of Nov. 2020.

Pre-recorded audio clips of one of Douglas and Schmidt’s in-person tours discuss historical events specific to Charlottesville in chronological order. From Liberation and Freedom Day — established to commemorate the surrender of Charlottesville to Union forces in 1865 — to the Albemarle tax that funded the construction of Confederate monuments, listeners can embark on an informative virtual journey through Charlottesville’s history.

Schmidt and Douglas both emphasize the importance of education and their desire to create a platform that could act as a free and accessible source of information for Charlottesville residents — and now participants in their virtual tour — to become informed and more aware about the history of the city.

“I see the tour's overall impact as public education,” Schmidt said. “That's what it's meant to do, so that local residents have an understanding of how it was that those statues were installed. A lot of people that have come on the tour have said it has changed their minds about what was going on, what they formerly saw as just innocuous statues.”

Elizabeth Varon, associate director of the U.Va. Center for Civil War History and member of the President’s Commission on the University in the Age of Segregation, discovered Marked by These Monuments while following Douglas and Schmidt’s work through social media and in the local news.

“The most important things to know about the Confederate monuments in the city is that they were intended to symbolize and to preserve white supremacy and Jim Crow discrimination,” Varon said. “[The monuments] enshrine the ‘Lost Cause’ myth of the Civil War — which glorified the Confederacy and swept the complexities of Southern history, including divisions within the South, under the rug.”

While information about the tour has usually been spread by word of mouth, conversations about the tour and its importance have started to pop up in educational settings. During a January term course called Art Now, a contemporary art history course that delves into the art of the past and the messages that the art continues to convey in present-time, third-year College student Kayla Foliaco was introduced to the online version of the tour through the course.

“I think that remote access to knowledge is so powerful,” Foliaco said. “Not only can people access the tour amidst a pandemic that made an in-person field trip impossible, but [it also] allows people who are differently abled or who do not live in Charlottesville to participate in an experience that would have been otherwise unavailable to them.”

The tour provides the tools to frame the symbolism and connotations behind Charlottesville’s Confederate monuments, which connects to larger practical conversations on what to do with other monuments that may be removed and more ethical conversations regarding the persistence of systemic racism today.

“We really need to engage in a new conversation about what it is that we as a community, and largely a nation, believe are representative objects ... because that is aesthetic space that says a whole lot about who you think you are as a community,” Douglas said. “We still have a long way to go to talk about what is a more authentic and inclusive discourse for the objects that we put in our public spaces.”