Lea en español

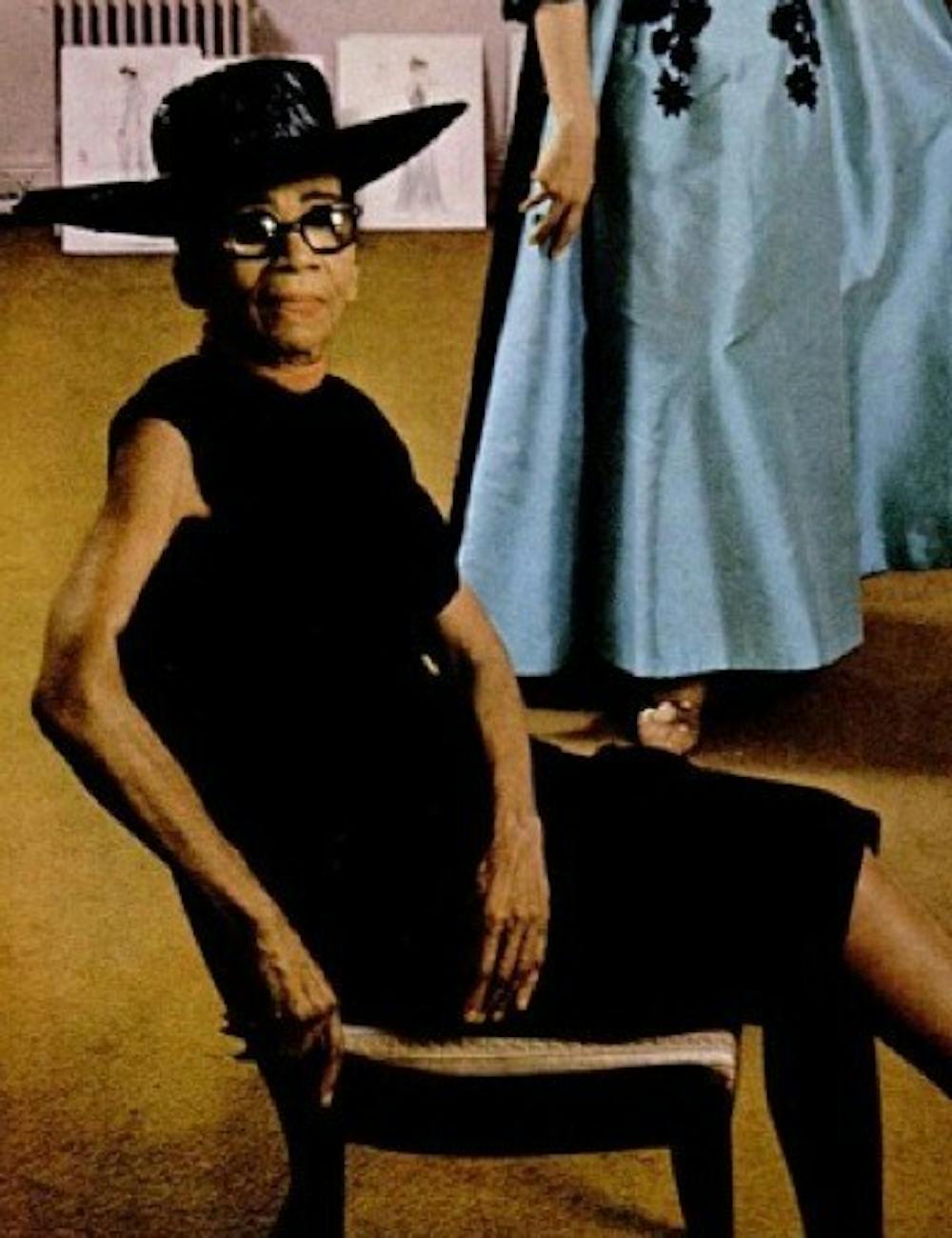

Jackie Auchincloss-Bouvier’s elegant wedding dress for her marriage to John F. Kennedy was one of the most iconic bridal gowns of the 20th century. But while everyone at the time fawned over the dress, very few knew who designed it. When asked by the press and others, Jackie merely responded that “a colored dressmaker did it.” That dressmaker was Ann Lowe, one of the most sought-after designers of high society in her time, unbeknownst to the public.

Lowe was born in rural Alabama in 1898 into a line of seamstresses. Both her mother and her grandmother, the latter of whom was born into enslavement, ran a dressmaking business for high society members of Alabama. Although Lowe learned to sew at a young age, her mother's death prompted her to take over the family’s business at 16 years old, beginning her love affair with fashion. According to CNN, this love of fashion took her all the way to design school in New York, where her skills enabled her to graduate exceptionally quickly despite being segregated from her white classmates.

Throughout her career, Lowe maintained a very particular clientele. As a self-proclaimed “awful snob,” Lowe told Ebony magazine in December 1966, “I am not interested in sewing for cafe society or social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the social registry.”

While her mission to only design for the upper classes was successful, her exclusive clientele demanded a level of perfection that often came at a cost. In the case of the aforementioned Kennedy wedding dress, when a flood hit only 10 days before the wedding, Lowe hastened to remake the dress and several bridesmaid dresses. The expensive materials and extra labor required for a gown fit for a society darling cost her over $2,000. When she arrived to deliver the labored-over dresses, she was told to enter through the back door, to which she responded that she would “take the dresses back,” reports the National Museum of American History.

Not only did she never receive credit for her work on the famed wedding dress, she also never received credit for many of her other designs. When "Gone with the Wind" star Olivia de Havilland received her award for Best Actress at the 1947 Academy Awards in one of Lowe’s designs, de Havilland went so far as to remove Lowe’s name from the tag. In this way, Lowe was frequently referred to as “society’s best kept secret,” a Black woman highly sought after by the wealthiest members of society, but never publicly given credit for her work because of her race.

Lowe’s finances also suffered because of her race. In order to keep up with her white competitors and appeal to the white women of high society, Lowe often lowered her prices excessively. When her son and bookkeeper died in 1958, she went into substantial debt and was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1962.

That same year, Lowe lost an eye due to glaucoma, meaning she could no longer sew her dresses herself or create her signature hand-painted flower designs. An anonymous benefactor — often speculated to be Jackie Kennedy — eventually paid off her debts, allowing her to continue designing for multiple years. Nonetheless, her career never fully recovered, and her business did not survive past her death on Feb. 25, 1981.

In spite of all the adversity she faced during her lifetime, Lowe has finally begun to gain some recognition. In recent years, two books have been written about her, and her dresses are spread across several museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of New York City and the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, where one of her dresses is currently on display.

Still, Lowe is not nearly as well-known as similar white designers of the time who built successful and long-lasting fashion houses. And she is not alone. Countless other Black creators throughout history have consistently been pushed into the background or forgotten while their influences impacted our culture, often with white creators getting all of the credit for progress initiated or aided by Black creators. The influence of Ann Lowe’s designs might not be visible in today’s fashion, but they certainly had an impact on the fashion of their time and on the better-known and higher-paid white creators of that time. Lowe deserved just as much credit as they were given, and her lack of personal recognition as well as her inability to fully expand her business cannot be ignored.

Today, Black designers still frequently take a backseat to white ones. To combat this, it is crucial to actively seek out Black designs and give their creators the credit and success afforded to so many other designers. It is also important to remember Black designers of the past who have been forgotten, even while their designs — like Lowe’s wedding dress worn by Jackie Kennedy or the streetwear fashion pioneered by Willi Smith — are remembered. This Black History Month, on the 40th anniversary of her death, remember Ann Lowe, the remarkable and influential Black designer who spent her life designing beautiful, beloved dresses without ever being allowed to become beloved herself. Use her memory to instigate change by ensuring that the Black designers of today do not go unnoticed or uncredited.

For more information about current Black designers, consider those featured in this article from Cosmopolitan or this one from Harper's Bazaar.