U.Va. Health is participating in phase three of a clinical trial for a COVID-19 antibody cocktail to stop transmission of the novel coronavirus in households where one individual has tested positive. The drug is administered to household contacts of a COVID-19 patient who have been exposed within a four-day period. It has shown promising results of immunity against symptomatic infections.

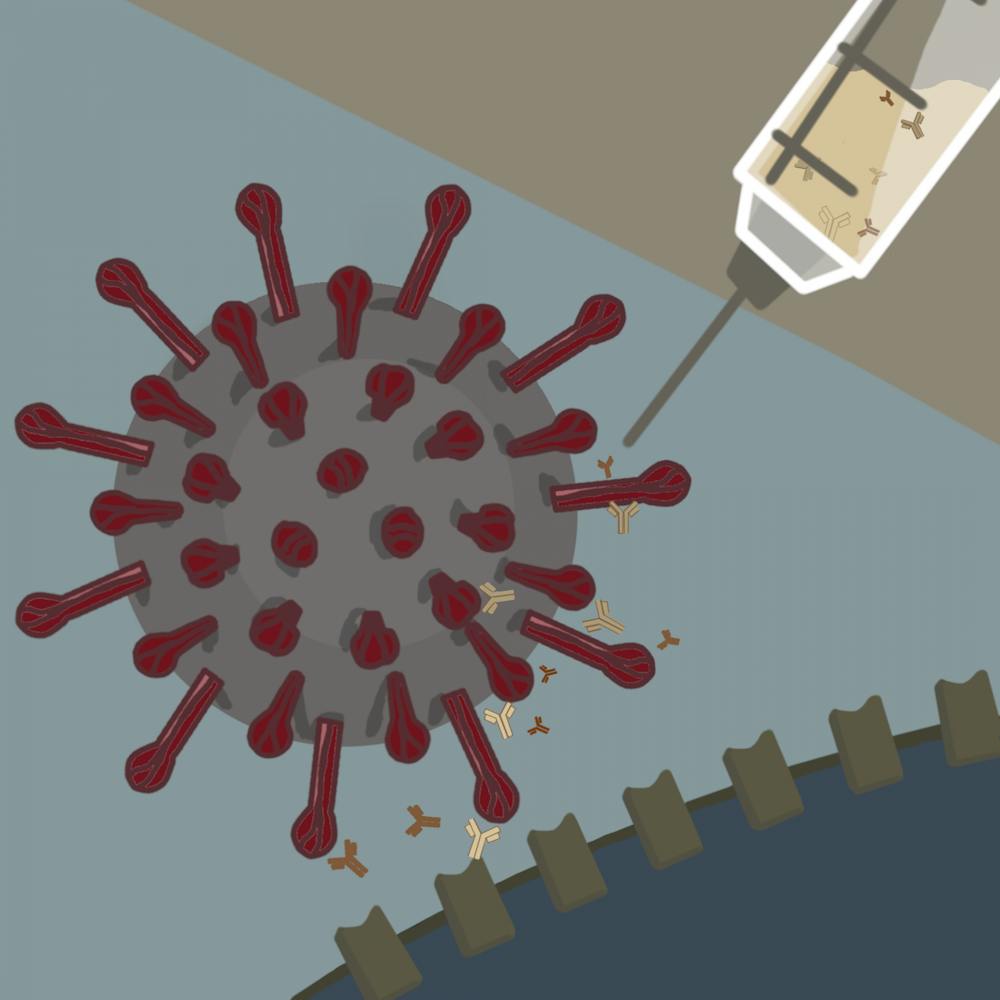

U.Va. Health is one of 150 sites in phase 3 of clinical trials for the drug created by Regeneron, a biotechnology company. The cocktail, which includes two different monoclonal antibodies for the spike glycoprotein of COVID-19, can be delivered as a self-administered injection.

When a patient is infected with COVID-19, the virus invades the body and multiplies copies of itself. The body’s immune system responds to the foreign material with white blood cells, which produce antibodies that react to the foreign material if the virus enters the body again. Monoclonal antibodies are copies of the antibodies that are made in a laboratory setting and target specific foreign substances.

William Petri, professor of Internal Medicine and Pathology and leader of the clinical trials at U.Va. Health, said that the spike glycoprotein, found on the outer surface of the COVID-19 virus, is essential for attachment of the virus to human host cells.

“The spike glycoprotein is the Achilles heel of the virus because [the COVID-19 virus] needs that spike glycoprotein in order to attach to the human receptor,” Petri said. “ If you can have an antibody that binds to a spike glycoprotein, it can totally prevent the ability of the virus to get inside of a cell, and in fact, that's a real advantage of the approach.”

The addition of two different types of antibodies against the spike glycoprotein of the coronavirus decreases the chance of the virus evading the body’s acquired immunity. Additionally, it ensures a level of protection against variants, including the U.K. variant, which arrived in the University community in February.

It was important for U.Va. Health to join Regeneron’s scientifically driven approach to analyze the potential role of the antibodies, according to Petri.

Rebecca Carpenter, fourth-year Medical student and sub-investigator for the study, worked on the project after the pandemic altered her medical school plans, allowing her to continue researching in Petri’s lab during this demanding time.

“I missed interacting with people in the clinical environment and looked forward to getting to do that again,” Carpenter said. “I particularly looked forward to getting to interact with people who are fearful and get to encourage and care for them in the midst of a lot of uncertainty.”

Physicians from the study reached out to household contacts of COVID-19 patients who had been exposed for a period of four days or less and had not received a previous positive COVID-19 test result.

“This study was set up that way because [researchers are] trying to prevent [transmission of] COVID-19,” Petri said. “The longer that you're exposed, then, the less ... opportunity [there’s] to prevent the infection.”

Carpenter was responsible for enrollment of patients for the trial, physical exams and documentation efforts under the supervision of a study physician.

“I swabbed patients for COVID-19 [and] I was frequently told that I was the favorite swabber, which I got a kick out of because I never thought that would be a skill I would perfect,” Carpenter said. “I also helped with study documentation, monitoring after drug administration including vitals and study follow-ups in conjunction with the clinical research coordinator.”

Carpenter described that during a patient’s initial visit to the clinic they took a rapid PCR COVID-test, had their blood drawn and received a physical exam. The drug choice was randomly assigned to a patient and then administered. Afterward, the patient would stay in the clinic for an hour so that physicians could monitor their vital signs in case an adverse reaction occurred.

Following the visit, patients received a weekly COVID-19 test during the first month and were monitored for any adverse effects. After that period, Igor Shumilin, clinical research coordinator for the study, said that further testing only occurred if a patient experienced COVID-19 symptoms during their 7 months with the study.

Although Regeneron has not filed an emergency-use application to the Food and Drug Administration yet, Petri notes that preliminary data for the study’s first 400 patients indicate promising results. Twenty-four of the study’s 3,500 patients were enrolled at U.Va. Health.

Results indicated that the antibody cocktail is 100 percent effective in prevention against symptomatic COVID-19 cases, and 50 percent effective at preventing infection overall when factoring in asymptomatic cases. If a patient develops COVID-19 following the cocktail treatment, they are likely to have an asymptomatic case and be infected with lower amounts of the virus.

Petri indicated numerous benefits of the antibody cocktail including self-administration that would be similar to how diabetes patients use insulin. Fundamentally, he notes that this is the first drug for COVID-19 that enables individuals to care for their loved ones who are infected with the virus without putting themselves at adverse risk. Furthermore, it is an effective treatment given the variability in cases as individuals get vaccinated and new variants emerge.

“It's like a stopgap until everybody is vaccinated,” Petri said. “In part, it’s something that will always be useful because there are always going to be situations where the vaccine’s not 100 percent effective or there's a new variant.”

Unlike the COVID-19 vaccine, the antibody cocktail only provides temporary, artificial immunity while the body begins to naturally form antibodies. Petri notes the half-life of the antibodies from the drug is approximately two weeks and serves as a way to jump-start the immune system.

“The antibodies are not long-lasting and so this is going to provide protection only for that period of time in which like your roommate or your spouse is infectious,” Petri said. “That's an important difference from a vaccine, which we're hoping [provides] very long-lived protection.”

Petri notes a challenge of the trial was conducting the clinical study in a safe manner that did not put other U.Va. Health patients at risk as COVID-19-exposed participants visited the clinic. He mentioned the key collaboration with Debbie Shirley, division head of Pediatric Infectious Disease and leader of the COVID-19 clinic, to reduce potential exposure to other hospital patients.

Patients adhered to precautions by wearing masks while the clinic’s staff used personal protective equipment to ensure safety. Additionally, Petri mentioned that patients could easily access the clinic outdoors, and thus did not have to enter the hospital, further decreasing the risk of exposure to others.

Petri indicates that the team has been following up with patients since mid-August and will continue to screen them every four to five months, to ensure the safety of participants. As of now, the cocktail has been tolerated well, and researchers have only seen reactions at the injection site.

Carpenter notes that the next steps for the trial will include determining where resources should be allocated. She is thrilled about the prospect of distributing the drug to places facing extreme isolation such as nursing homes and retirement communities.

“I think the next step is identifying which communities and situations would most benefit from this cocktail to prevent COVID infections and subsequent morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 and also allow maximum return to normalcy in our communities,” Carpenter said.