Lea en español

The University of Virginia is affectionately referred to as “Mr. Jefferson’s University,” as it was this Founding Father’s own brainchild, intended to compete with the eminent universities of the north. Since its inception, the University has become a prestigious university with a healthy endowment and many prominent graduates. Many students though, while proud to attend the University, are deeply troubled by Thomas Jefferson’s and the University’s role in perpetuating policies of racial oppression. The University has acknowledged the need to address that harm and has started making investments in programs to acknowledge its role in perpetuating the oppression of enslaved laborers.

However, a seldom explored aspect of Jefferson’s legacy was his impact on American Indians. Jefferson had a prominent role in displacing Natives, whom he acknowledged in “Notes on the State of Virginia” as being present around Monticello. The land where the University sits today was once the home of Monacan people, who cared for the land. Jefferson contributed to their removal and the removal of other nations all across the country. As President, Jefferson promoted the “civilization” of Native Americans, also known as forced assimilation.

In the 200 years since the University’s establishment, little has been done to atone for the sins of this school’s founder. If anything, the University has only further perpetuated the same attitudes until very recently. A century ago, the field of eugenics was booming and the University was at the forefront of this pseudoscience. The Commonwealth of Virginia as a whole is infamous for the role of Walter Plecker in the erasure of Native Americans and the segregation of African Americans. These same ideas that undergirded the policies that became the “Racial Integrity Act” were once taught at the University as scientific fact, affirming white supremacy.

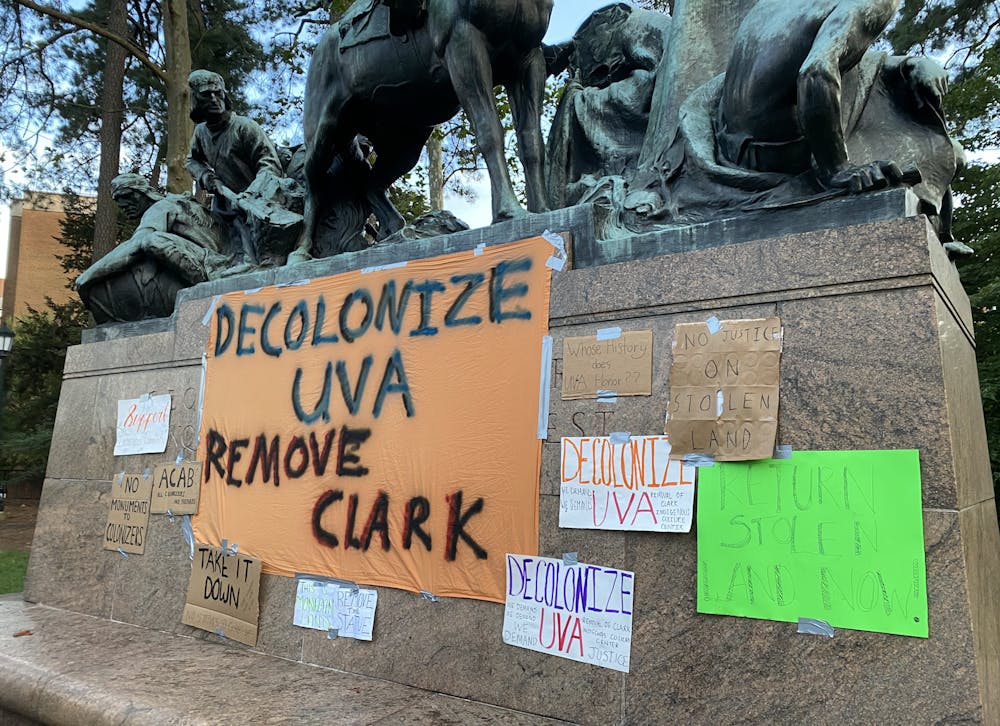

Statues celebrating Confederate soldiers were erected to intimidate African Americans, who had just fifty years prior been freed from the shackles of slavery. In addition, statues depicting Native Americans were also constructed, highlighting the “conquest” of the New World from the noble “savages'' of the wild frontier, such as the statues of Sacajawea and George Rogers Clark here in Charlottesville. The one of George Rogers Clark sits on University Grounds and depicts this valiant white man, leading his soldiers in the merciless slaughter of unarmed Indians, with the inscription, “Conqueror of the Northwest.” Both of these statues have been slated for removal after years of protest and advocacy by Native Americans.

With such negative portrayals, I can tell you that as a Native American it is sometimes painful to be a student at the University. It is hard to find any representation that presents my family’s history in a way that is authentic and affirming to my identity. As a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, I know my ancestors fought against the forced removal, which would come to be called the Trail of Tears. They eventually left as Old Settlers — those who removed on their own before the Trail of Tears that removed the majority of Cherokees.

Jefferson contributed to the political movement that resulted in that forced removal. In writing the Declaration of Independence, he noted the King’s treaties with Indians as one of the causes for separation from England, claiming he had incited insurrections from “merciless Indian savages.” Part of his motivation for purchasing the Louisiana territory was that it would be a place to which American Indians in the east could be moved to, and he openly discussed Indian removal with his Cabinet.

My ancestor, Charles Hicks, was prominent in the early 1800s and fought Jefferson’s attempts at diminishing Cherokee sovereignty and land claims. But the history of my nation or that of the many other nations across what is now the Commonwealth of Virginia and the United States is hardly found in the curriculum. Programs celebrating modern Native Americans and exploring modern Native culture, art and political movements are anemic. Native Americans are underrepresented in the faculty and student body, classes on topics relating to Native Americans are scarce and a minor in Indigenous studies is only now being considered. William and Mary and Virginia Tech both offer a Native Studies minor and have a tribal liaison. The University, on the other hand, has no dedicated staff to support Native American students or advise students seeking to study Native issues. Students wishing to concentrate in Native American studies must be creative and build their own plan, often utilizing related coursework in place of classes focused on the actual topic of interest. The University and this administration offer bargain bin novelties and lip service rather than considering any legitimate proposals, and then take credit for the work of Indigenous people and allies.

The University must begin taking steps to actively confront its history and that of its founder. We must begin acknowledging that painful past and work towards rectifying it so future Native students feel welcome here. The University must examine their admissions practices to find out why Native students are under-accepted and under-enrolled. We must begin immediate work towards a Native American and Indigenous Studies Center, with dedicated space for faculty to work and for Native students to socialize. There needs to be a dedicated position within the University to consult with the Virginia tribes to improve relations and seek vital input on programs that may impact them or their citizens, especially those attending the University. Piecemeal tokens are no longer enough.

Zac Russell is a third-year student in the College and Social Chair of the Native American Student Union.