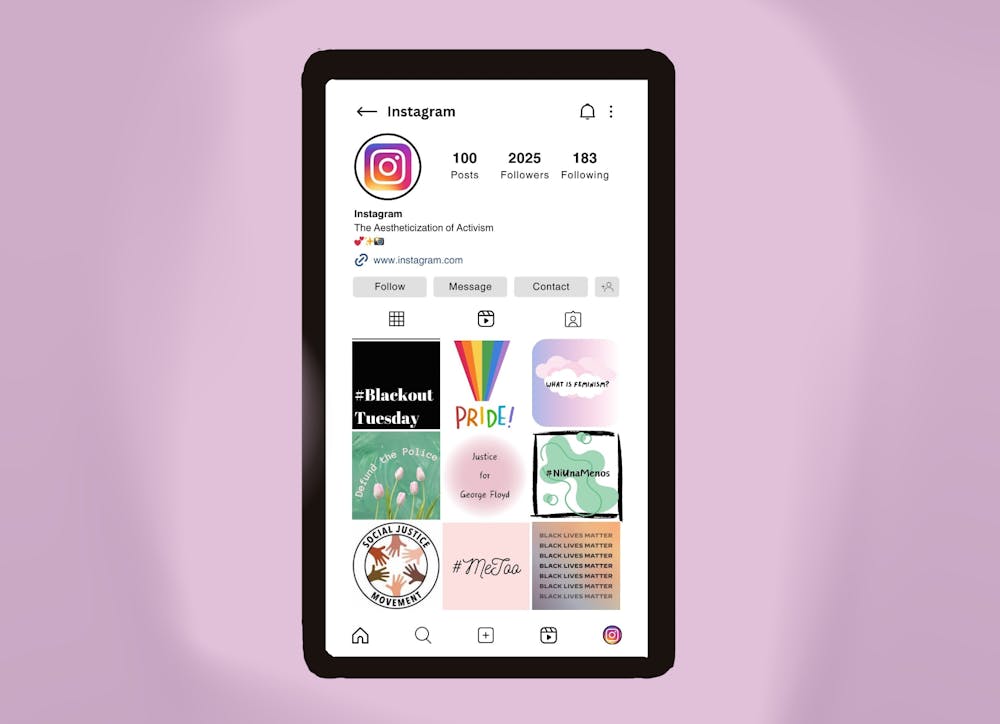

On June 2, 2020, I vividly remember calling my friend to discuss #BlackoutTuesday on a quarantine walk, making my way through the neighborhood trail with the Virginia humidity hanging thickly in the summer air. She reposted the black square — I had not. #BlackoutTuesday was a form of collective support for Black Lives Matter organized within the music industry, calling for the industry to halt business and contemplate its contributions to racism. Since I had never posted anything related to social justice before, it felt performative to start now. I was unsure of exactly what made me so uneasy, but seeing people who let racist comments slide in high school conveniently repost a black square was upsetting. She agreed, but pointed out the importance of showing solidarity and raising awareness, especially given that neither of us would be able to attend the Black Lives Matter protests given COVID-19 concerns. We both hung up slightly doubting our separate decisions.

Later that day, I found out that misinterpretation of the post’s original intent had led to an influx of the posts under the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, crowding out a channel that organizers used to post important information. In the following weeks, I was bombarded with clean, pastel-colored infographics on people’s stories, and I struggled with reposting those as well. When even reposting a black square can have such nuanced impacts, navigating meaningful activism on social media becomes a minefield. Nonetheless, the momentum Black Lives Matter gained last summer demonstrated the power and ubiquity of social media in activism.

These aesthetically pleasing social justice infographics on everyone’s feed are not contemporary inventions. They started out in the early 1900s as “data portraits” created by civil rights activist and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois as part of the “Exhibit of American Negroes” at the 1900 Paris Exposition. The exhibition aimed to illustrate and commemorate the lives of African Americans and at the time was many people’s first exposure to the reality of Black people’s everyday lives in America. These data portraits were so revolutionary because they broke from academic tradition and appealed to people outside the circles of scholars that sociological research would typically reach. Over 100 years after Du Bois’ innovative data portraits, this use of graphics as a visual language still lends itself well to activism outside of traditional institutions of social change — especially on a medium like Instagram built specifically for aesthetic appeal. Yet these once revolutionary inventions are so easily produced and spread that they have reached a point of oversaturation. When compounded with an algorithm that prioritizes aesthetics, creators face pressure to make their infographics increasingly eye-catching.

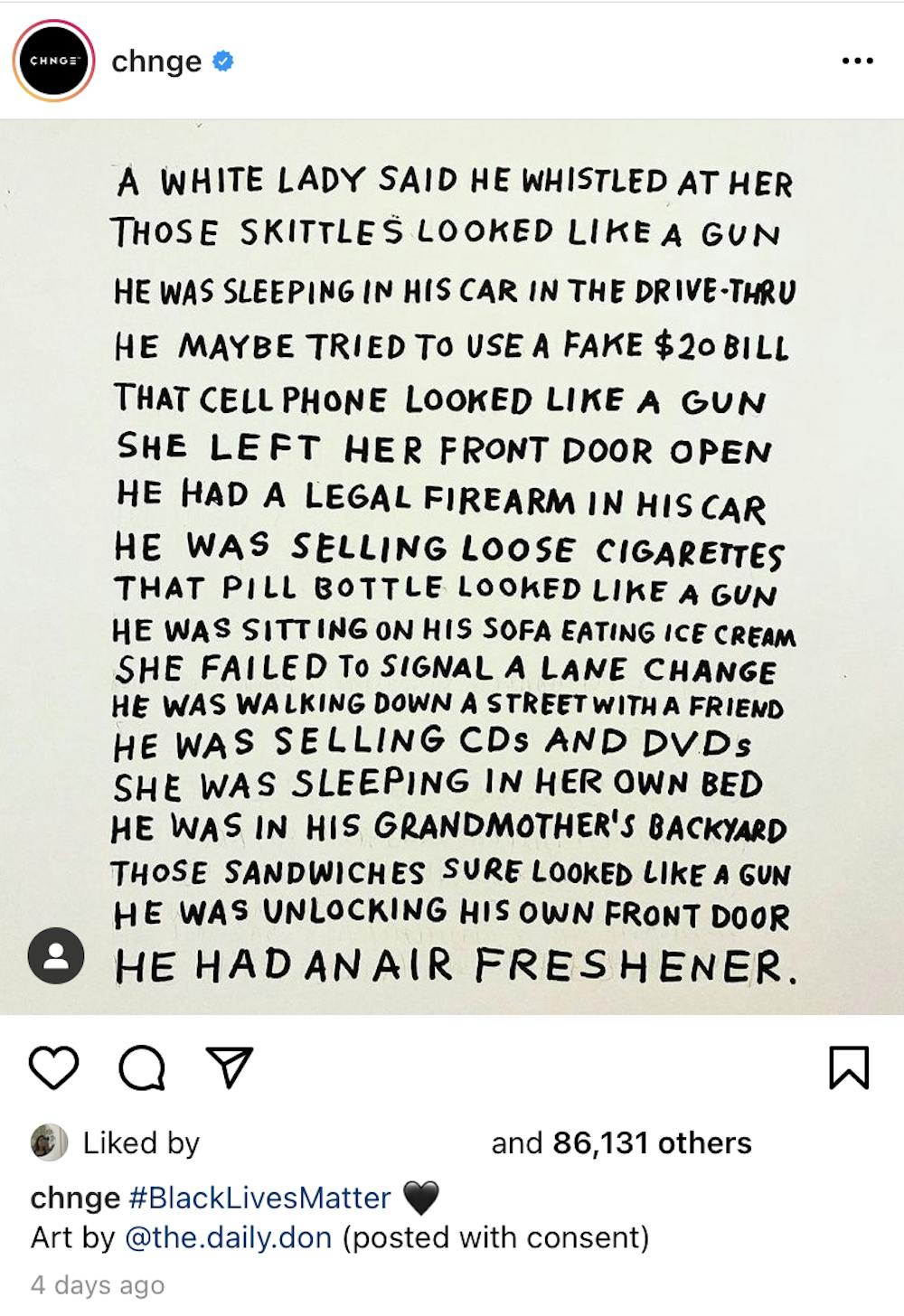

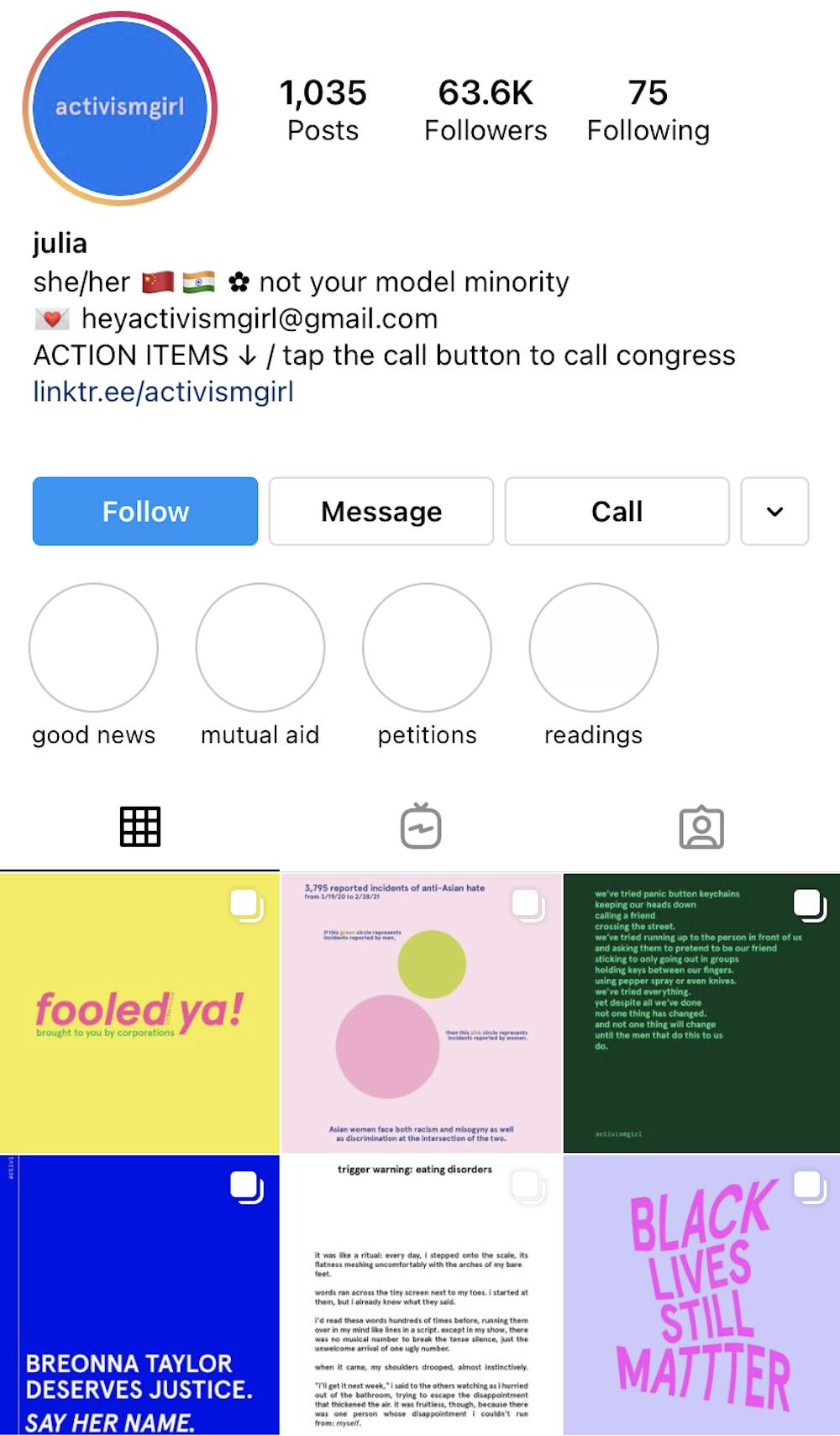

Most people have likely seen these infographics on their feed, which Terry Nguyen of Vox defines as “text-based slideshow graphics'' characterized by “colorful gradients, large serif fonts, pastel backgrounds, and playful illustrations.” These deliberately neutral infographics are used to appeal to a wide range of users and are aesthetically similar to the graphics that millennial-oriented brands utilize. Initially, the method of social currency accumulation on social media was aesthetic appeal and strong personal branding. Following the tipping point last summer when George Floyd was murdered amidst a global pandemic, the norm shifted. Now, it is almost a necessity that one demonstrates their social awareness online. Shrewd brands who recognize this have capitalized on the wide aesthetic appeal of infographics. This co-optation of social justice allows brands to hide under the guise of activism while simultaneously practicing deeply problematic behavior. On June 1, 2020, women’s clothing retailer Anthropologie posted a Maya Angelou quote, since removed, which emphasized the importance of diversity — yet it neglected to mention Black Lives Matter by name. Later that week it came under fire for its lack of diversity and racial profiling of Black customers by referring to them with the code word “Nick.” This type of posturing integrates perfectly with a brand’s social media feed, yet an evaluation found that most corporations failed to follow through on promises of racial equity they made over the summer.

The Limitations of Infographics

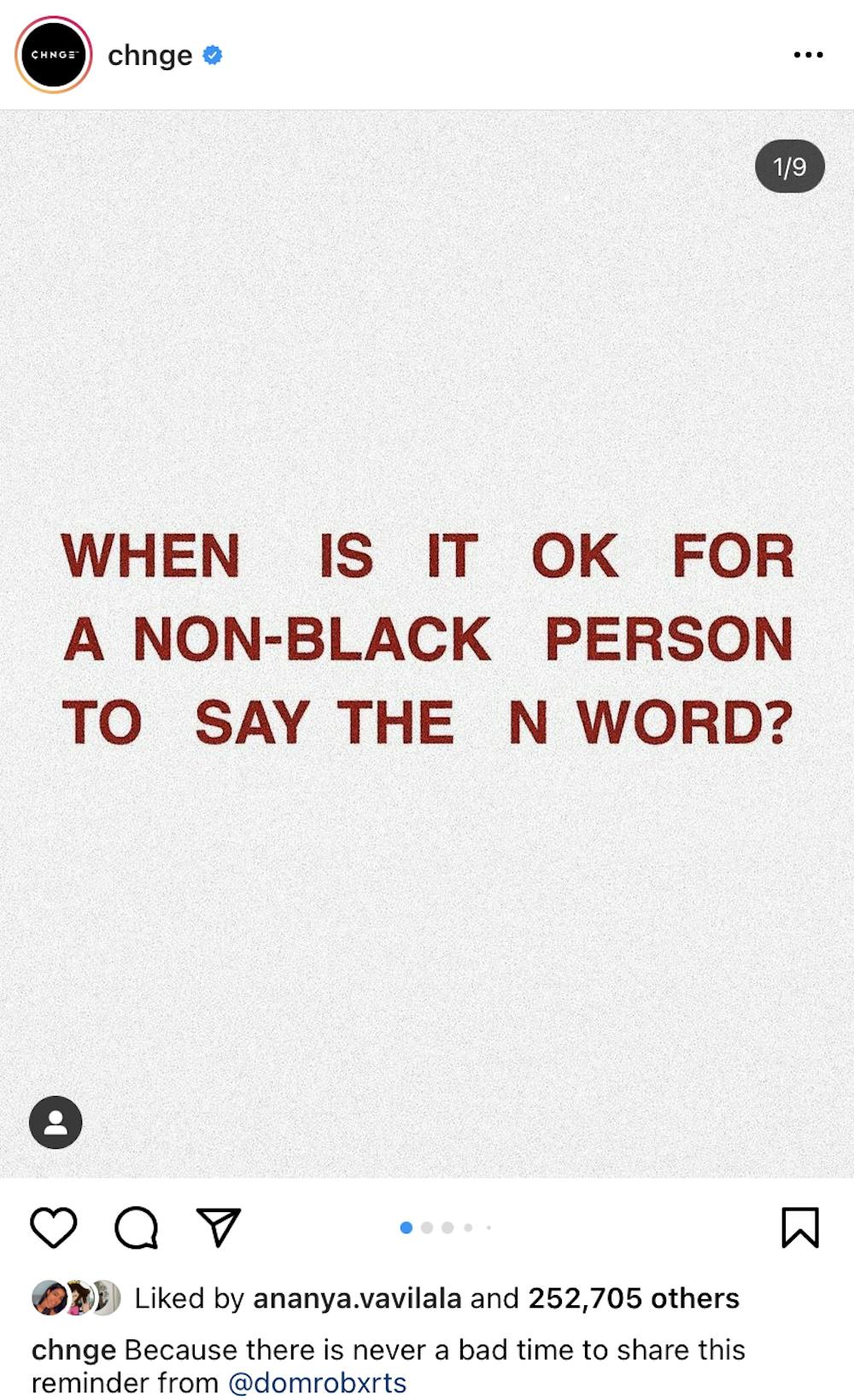

While infographics did help to bring the Black Lives Matter movement into the mainstream, it is important to understand their limitations. Social media functions as an echo chamber, so the awareness that they bring is very diffuse. People’s social networks are generally limited to those who share similar opinions and interests, and those on the fringes are unlikely to be swayed by an infographic. Thus, infographics’ greatest utility is their ability to bring issues into the mainstream and normalize them. For example, Black Lives Matter was seen as much more radical and controversial in previous years, but social media helped change public perception of the movement this past summer. Yet the power of infographics is corrupted when people allow the entirety of their activism to remain on social media. Structurally, social media only allows for surface-level activism — from Instagram’s prioritization of images over text to the 10-slide limit of its carousel posts, information about complex issues must be forced into bite-sized, algorithmically compatible snippets.

Social media also facilitates a feeling of self-importance that overamplifies the impact of infographics. Writer Jia Tolentino argues in her essay collection, “Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion,” that social media deliberately distorts our sense of self and facilitates the sort of virtue signaling that contributes to performative activism. The way that these platforms are set up are so oriented around the self, or connecting with others through the self, that it makes us seem proportionally more important than we are. When Facebook prompts users to display their favorite movies on their profile or when Instagram displays a following to follower ratio, we are the focal point of the experience. More specifically, the focal point is how much optics-based social currency a user has.

Philosophers like Judith Butler argue that our identities are constructed entirely by performing norms and expressions to others. When others perceive us and our expressions, it validates our belief that we are, in fact, the people that we are performing to be. Social media strongly facilitates this given the convenience of validation, which is just a like or comment away. It is a tool to platform our identities and simultaneously shape them as well. This is why it is so conducive to the practice of virtue signaling, which aims to perform moral superiority rather than genuine good.

By orienting the platform around granting and receiving instant gratification in the form of likes, Instagram signals that our opinions are much more important than they actually are. Thus, an act such as reposting an infographic automatically signals to our followers that we, too, are woke. Social media has distorted substantive civic engagement to create the illusion of discourse, but the ability to disengage so easily enables avoidance of difficult conversations. These limitations, combined with the reward system that social media creates, facilitate performative activism, which creates the guise of pushing for change without achieving something substantive.

Moving Forward

The question then becomes where this leaves us and what role social media should play in activism. It does have value in creating spaces and norms, especially given its wide reach and accessibility. But moving forward, it is important to be conscious of its limitations. Social media demands radical and immediate change, when in reality commitment must be sustained and over the long term. #NiUnaMenos is an Argentinian movement against gendered violence that started in 2015. Through heavy reliance on social media, it was able to maintain consistent political salience and successfully push for the legalization of abortion in 2020. Still, this change occurred gradually, and there is much work to be done. So sharing information and resources is important during tipping points like the one last summer, but it is also necessary in less tumultuous times.

Another part of this is accepting that tensions will always exist. People will post infographics both because they care about a cause and because it is aesthetically pleasing and contributes to their woke persona. When people don't fit the perfect activist mold — perhaps they respond in a slightly misinformed manner or fail to post an infographic — they are often sanctioned. Yet this behavior fails to recognize how complex and personal activism is to each person. Policing others makes perfect the enemy of the good, but the most sustainable way to push a movement forward is together. Having empathy for oneself and others and accepting mistakes as a necessary part of growth will lead to much deeper activism than the surface-level engagement that social media allows.

Social media and politics are now irrevocably intertwined. Consequently, engaging in activism in today’s world where every action has unintended consequences can be overwhelming. The contradictions and tensions of social media activism existed during #MeToo, they continued during the protests with George Floyd over the summer — and more recently with Daunte Wright — and they will persist for the foreseeable future. Yet social media as a mechanism of incremental change and as a supplement for in-person activism can be truly powerful. The key to optimizing this power is understanding its value and limitations, both at an individual level and as a collective.