COVID-19 antibody testing and research conducted this past summer in various regions of Virginia by University researchers indicated relatively low antibody presence among the state’s population. By testing for antibodies, researchers aimed to better understand the feasibility of achieving herd immunity yet found evidence that shows that immunity itself cannot be reached through antibody production alone.

The immunological naivety, or lack of protective COVID-19 antibodies, of Virginia’s population serves to further emphasize the importance of continued vaccine distribution and the maintenance of public health measures as ways to limit the spread of the virus and acquire herd immunity as safely as possible.

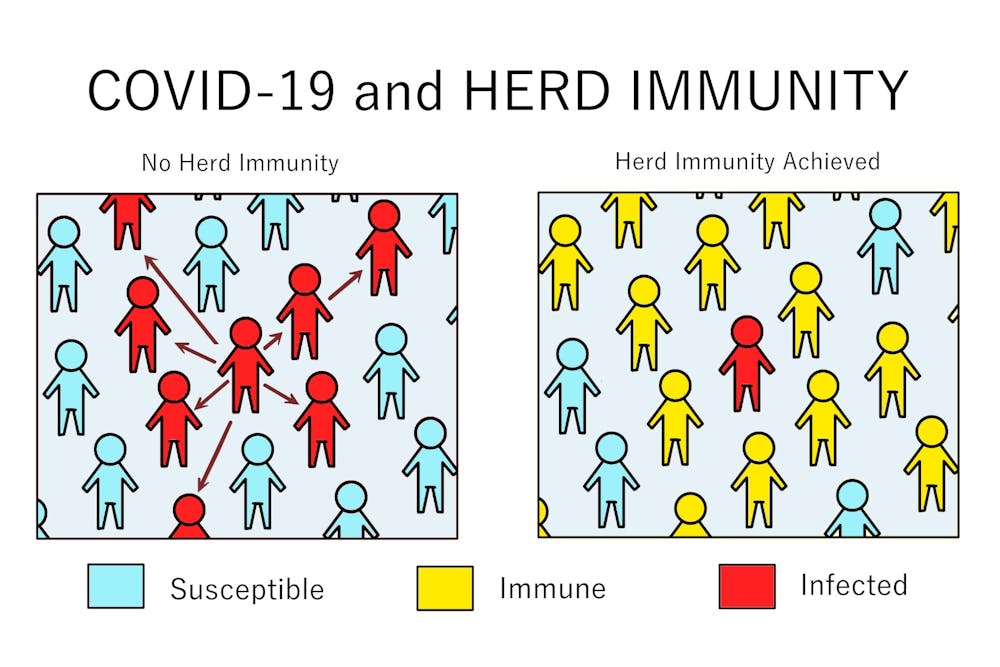

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, clinicians and general citizens have questioned if herd immunity can plausibly be used to end the pandemic and allow individuals to return to daily life. Herd immunity is when enough people in a given population possess antibodies against a virus and are immune to it, which makes them unlikely to contract the disease upon exposure as resonated by Costi Sifri, director of hospital epidemiology.

“[Achieving herd immunity] means there just is not the chance for COVID to be easily transmitted from person to person in different settings, and so at that point, some of the protective measures can be eased,” Sifri said.

Eric Houpt, infectious disease and internal medicine specialist at U.Va. Health and principal investigator of the Sars-Cov-2 antibody prevalence study, details the ways in which herd immunity can be acquired by the population.

“There are two ways to get there — enough people get infected and recover and/or enough people get vaccinated,” Houpt said in an email to The Cavalier Daily. “The first option means lots of people will get sick and die, so we want the second option.”

Understanding the number of individuals containing antibodies necessary to establish herd immunity requires determining the contagiousness of a disease. Given COVID-19’s high rates of transmissibility, the anticipated percentage of the population who should have immunity is approximately 70 percent, according to studies done by the CDC.

In order to figure out Virginia’s status of antibody prevalence, which would determine the feasibility of acquiring herd immunity within a reasonable time frame, U.Va. Health researchers — including Houpt and Elizabeth McQuade, assistant professor in the department of public health sciences and the division of infectious diseases and international health — conducted a cross-sectional study of adult outpatients to investigate how many Virginians likely possessed antibodies by the end of the first coronavirus wave. Antibody data was collected between June 1 and Aug. 14 of 2020.

“Over a couple of months, in sites that were geographically distributed around the state, we enrolled participants and looked for antibodies to the SARS-Cov-2 virus, which indicates that the person had been previously infected with the virus,” McQuade said.

Seroprevalence testing for COVID-19 antibodies measures antibodies present in the blood of an individual through venipuncture. Studying the seroprevalence of Sars-Cov-2 is important because many people who get infected with COVID-19 remain asymptomatic and often do not receive a positive result, making state case counts not fully representative of COVID-19 prevalence. At the time of the study, approximately 0.7 percent of Virginians were recorded as having received positive COVID-19 test results.

The researchers chose to test seroprevalence at five different outpatient sites across Virginia, enrolling a total of 4,675 adult patients. Each of the selected sites enrolled approximately 1,000 patients who had not tested positive for COVID-19. They additionally strived to recruit a diverse sample of participants who were truly representative of residents of Virginia, due to studies that showed that COVID-19 affects various demographic populations differently.

“[We] spent a lot of effort to ensure that the individuals that we were enrolling are representative of Virginians by their race, ethnicity, age group, etc.,” McQuade said.

Access to a diverse participant pool was facilitated through hand picking outpatient sites in geographically diverse regions of Virginia, including the U.Va. Health system to represent the northwest region and Virginia Commonwealth University for the central region.

The results of the cross-sectional testing revealed that, as of August 2020, the number of adults who were exposed to COVID-19 — an estimated 2.4 percent of the population — was only 2.8-fold higher than the number that was ascertained by the state of Virginia’s PCR testing, which revealed 74,155 cases. Approximately 66 percent of the patients with antibodies were suspected to have had asymptomatic infections, which went virtually unrecorded.

However, this statistic still falls significantly shorter than previous estimates which have ranged from 6-fold to 53-fold of the number derived from recorded case counts alone.

“[The data] certainly suggests that a very large proportion of Virginians probably still have not been exposed,” McQuade said.

The results also revealed differences in the infection rates amongst various populations. For example, seroprevalence was at approximately 10.2 percent among Hispanic individuals, which is comparatively higher than the statistics found in other demographic groups. This higher incidence is likely attributable to having a higher likelihood of Hispanics to reside in multifamily units and have contact with an individual with confirmed COVID-19 infection through job-related circumstances, as further shown by the study.

Additionally residents of Northern Virginia had a seroprevalence of approximately 4.4 percent, individuals aged 40 to 49 had 4.4 percent and uninsured individuals had 5.9 percent.

“There are a lot of complex factors involving resource limitations, structural racism and access to testing, especially,” McQuade said regarding the results on differential antibody prevalence in demographic populations.

Given that this study was conducted in the summer of 2020, more Virginians have been exposed to the virus and have had antibody production take place in recent months, leading to an increase in the percentage of Virginians with immunity established. Vaccinations were unavailable at the time of the study whereas they are currently becoming widely available, resulting in 16.1% Virginians being vaccinated as of April 1. Additionally, case counts in Virginia have risen from to 74,155 from the time of the study to 620,801 as of April 1.

“There are estimates nationwide that maybe up to 25 percent or so of people in the United States have been exposed to COVID,” Sifri said.

However, this predicted percentage of antibody presence is not without uncertainty due to lack of evidence on how long-lasting and protective COVID-19 antibodies are. A recent study from the ongoing Phase 3 clinical trial of Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine suggests that protection can last up to six months following the second dose and it is also effective against the B.1.135 virus variant.

“Someone who's been previously infected might be immune for a short time, meaning they can't get infected again for a short time, but then they might be at risk again later and that can perpetuate the transmission of the virus,” McQuade said.

However, the nuances of antibody retention and probability of contracting the virus is dependent on several factors such as the underlying functionality of the immune system. Sifri added that in individuals who have been infected with COVID-19 before, the immune system is able to exhibit heightened memory elements, which can allow the immune response to be “reawakened” upon consequent exposure to the virus.

As for the current status of achieving population-wide herd immunity through steady vaccination efforts, health professionals have said that significant vaccination efforts are still underway.

“We want to get up to about 70 percent of the population vaccinated,” Houpt said. “ We are nowhere near that number yet.”

Currently, the vaccination distribution effort in Virginia has resulted in 29.5 percent of the population being vaccinated with at least one dose and 15.8 percent fully vaccinated. The state is continuing to vaccinate individuals in phase 1a and phrase 1b, which includes many essential workers, individuals over age 65 and individuals ages 16-64 with high-risk medical conditions. Some health districts have also begun vaccinating those in phase 1c, which includes more essential workers, such as food service and public safety employees.

However, with the continuation of widespread vaccination efforts throughout the country, health professionals are optimistic about the possibility to potentially achieve some form of herd immunity in the coming months.

“Through the spring and maybe by early summer, if we've distributed enough vaccines, that — in combination with natural infection — [could mean] we've achieved some level of [immunity], it's approaching this herd immunity concept,” Sifri said.

Nevertheless, given the continued uncertainty and constantly evolving situations, health officials continue to emphasize the importance of following public health measures including social distancing, regular mask-wearing in public spaces and hand-washing.

With the final goal of herd immunity and a return to normalcy in mind, professionals additionally stress the importance of vaccinating all individuals, encouraging proactively registering to receive the vaccine and spreading the word amongst family and friends. Virginians may pre-register to receive the vaccine in Virginia by going to https://vaccinate.virginia.gov/ and following the listed instructions.