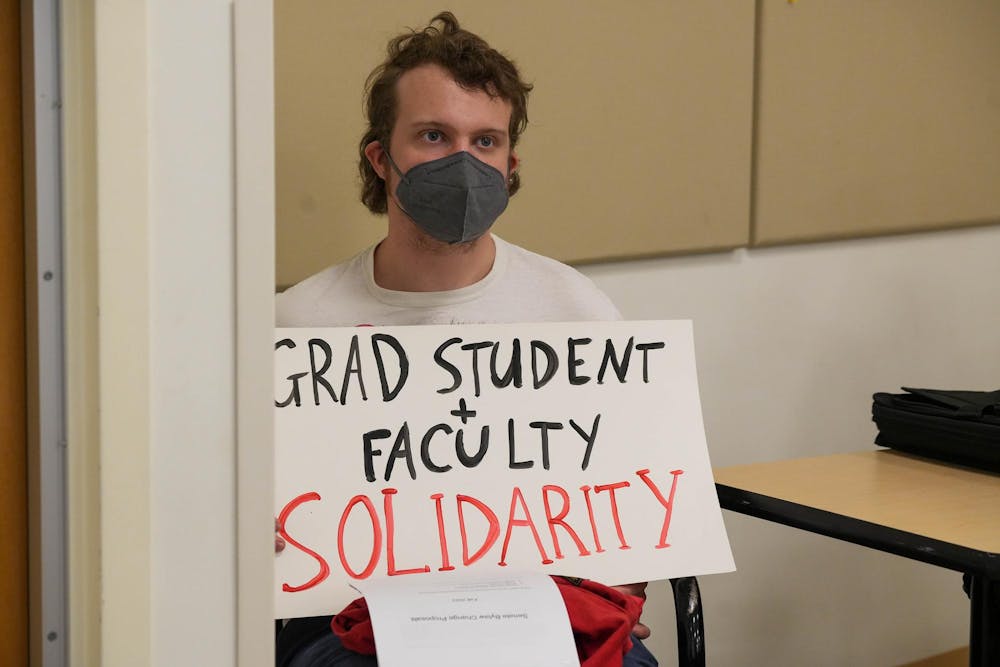

The University chapter of United Campus Workers of Virginia launched its premier graduate student campaign entitled Respect and a Fair Deal for Graduate Workers on May 1, International Workers Day. The organization is calling for improved working conditions for graduate students through clear terms of employment, a living wage and better healthcare.

UCWVA-U.Va. is a wall-to-wall union, meaning that it is open to anyone receiving a paycheck from the University including students, employees, faculty and staff. The organization previously campaigned for better working conditions at the University hospital amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, organized a “die-In” to protest the University’s fall 2020 reopening and launched the #ActFastUVA campaign last spring.

UCWVA-U.Va. released a petition alongside its May 1 campaign announcement that has amassed over 430 signatures, with over 400 of those collected by May 9. The petition, which is addressed to University deans, acknowledges the difficult year that the COVID-19 pandemic has created for all members of the University community and recognizes the University’s efforts to ensure student education despite the pandemic. Such efforts include demanding “great sacrifices from its workers, many of whom have been asked to report to work in-person, forego raises or endure furloughs and pay cuts, and put in extra hours,” the petition said.

According to University Spokesperson Wes Hester, the University has helped alleviate economic hardships by increased funded internships and other funded opportunities.

“The University has centrally directed more than $1.3 million in federal and institutional funds to graduate students for pandemic relief,” Hester said. “This figure does not include more specific, school-based efforts.”

The group has three key demands — that the University pays all graduate students workers a living wage of at least $31,300 a year and a minimum of $15 an hour, that all graduate student workers receive employee healthcare, including vision and dental insurance, and that the University issues clear and standardized terms of employment that address current hour, wage and expectation discrepancies as well as written disciplinary measures and recourse should terms be violated.

These demands come after many graduate students have worked additional hours without subsequent compensation over the last year while others have the lost work opportunities they depend on to remain in Charlottesville. The pandemic has “underscored and revealed longstanding inequities and vagaries currently inherent to working as a graduate student,” UCWVA-U.Va. said.

The University’s graduate student workers have performed many essential University functions both before and throughout the pandemic — they run labs and discussion sections, teach classes, maintain connections with undergraduate students through Zoom, create instructional material adapted for pandemic learning conditions and familiarize faculty with Zoom, Collab and other remote learning platforms. Additionally, members of the School of Nursing and School of Medicine served as frontline workers throughout the pandemic.

“Despite the fact that we perform all this essential labor, graduate student workers are still almost exclusively spoken of and treated like students by the University,” UWCVA-UVA said.

Graduate student workers serve as both students and employees of the University, taking courses and participating in research as students, though many depend on the money they earn as workers for rent bills, healthcare and child-care.

Stephen Marrone, a philosophy doctoral candidate in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, has experienced significant discrepancies as a University student versus employee.

“My experience as a student has been fantastic,” Marrone said. “But my experience as a worker hasn’t really lived up to that.”

One of Marrone’s struggles as a graduate student is with pay discrepancies. While Marrone makes $22,000 a year in the Philosophy department, a graduate student in the Biology department with the same teaching load makes $31,000 a year. Marrone said such pay discrepancies make him feel less valued.

Jesscia Swoboda, an English doctoral candidate and former first-year writing instructor, shared Marrone’s sentiments.

“The University does not see all labor as created equal,” Swoboda said.

For instance, doctoral students in the English department teach the first year writing courses that all first-year students at the University are required to take, yet Swoboda feels as though the work doctoral candidates do as an instructor is valued less than if completed by other contract employees or faculty members.

According to Hester, the University sets compensation ranges, rather than specific salaries for graduate students and all other employees with similar roles.

“Every department is subject to the same wage range for the same role,” Hester said. “Variation within those ranges across departments can be attributable to a variety of factors, including the scope of responsibilities, experience, market rate, disciplines.”

Graduate student workers have also struggled with insufficient healthcare coverage.

Any graduate teaching or researching assistant who earns more than $5,000 a year is entitled to a single coverage student health insurance subsidy that cost $2,980 for the 2020-2021 academic year, Hester said.

According to Hester, the cost of the student health insurance plan is the same for all students — all graduate assistants receive a 100 percent subsidy for the annual premium.

While the University provides total student health insurance subsidies for all eligible graduate student workers, many feel that the healthcare plan is insufficient to meet all graduate students medical needs.

“While [this] policy more or less works for those of us who are single, childless and able-bodied, many graduate students have needs the plan does not accommodate,” UWCVA-UVA said. “The current policy makes graduate degrees much more difficult to pursue for students with children or who are trying to family plan. Further, the inadequacy of the plan means that we are all one medical emergency away from abandoning our course of study.”

For graduate students such as Marrone, the student health insurance plan means that a typical hospital stay would cost $5,000 in deductibles plus 20 percent of the medical bill out-of-pocket.

“That’s a problem when I make below what’s considered a [living] wage,” Marrone said.

According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a living wage in Charlottesville constitutes an annual salary of approximately $31,300 a year or a $15 per hour wage rate.

According to Hester, graduate student wages currently fall between the Virginia minimum wage of $9.50 per hour and a University-determined maximum of $25 an hour. For graduate assistants working contractually 20 hours per week, the minimum possible wage rate is $12,000 for a 9-month academic year, which amounts to $15 per hour.

In addition to low wages and pay discrepancies, graduate students — including fifth-year History doctorate candidate Rosa Hamilton — often do not have clear and written terms of employment that outline their rights and responsibilities as workers. Subsequently, they often work additional hours in order to provide undergraduate students with a quality education.

“It was never clear … what our responsibilities actually were,” Hamilton said. “I was told that I should work 10 hours a week, but I was actually always working 20 to 30 [hours a week] at least.”

Hamilton described how the ambiguity of her contractual responsibilities precipitated a discrepancy between her official number of work hours a week and the amount of time required to adequately provide undergraduate students with a University standard of education. In a typical work week, Hamilton spends three hours lecturing, three hours leading discussion sections and two hours in office hours. The remaining two hours of her 10 hours a week is spent grading papers and assignments and responding to student emails.

“If you do the math on two hours for 60 student essays … you're asking graduate students to spend two minutes grading an assignment that students have [spent] a week on,” Hamilton said. “Students are suffering if that’s [the case].”

Therefore, Hamilton — like many graduate students — works additional hours each week to ensure the quality of essay and assignment feedback she gives her students.

“[TAs put in more hours] because of our commitment to making sure that students have [the] education that the University so desires of them,” Swoboda said. “But there’s a point at which we’re going to break.”

University wage authorization currently stipulates a 20-hour work limit for all students. The UWCVA-UVA‘s demands asks for $31,000 per academic year, which amounts to $15 per hour over a 40-hour week.

In January 2020, the University officially increased its employee minimum wage to $15 per hour as part of a new living wage plan. This plan covered 1,323 full time University employees, 800 full-time contracted employees and affected roughly 96 percent of the University’s workforce. It did not include graduate student workers.

Kelsey Huelsman, an Environmental Science doctorate candidate, discussed the financial instability and precarity of being a graduate student at the University, describing how graduate school is only accessible to individuals with particular life circumstance — namely, those who are young, without health problems, children or significant undergraduate debt and who have financial support from their families.

“My support system is that I was a full-time teacher before I started graduate school … and I lived with my parents for years and avoided paying rent,” Huelsman said. “If I hadn't done that, I wouldn't be afloat right now.”

From a healthcare perspective, Huelsman describes how although many 20-year-old graduate students are on student healthcare plans, she is no longer in her twenties and Student Health insurance no longer satisfies all her medical needs.

Because Student Health insurance policies do not cover vision or dental insurance, Huelsman pays an additional $300 a year for a dental plan. She said she is lucky to have decent vision, but many of her colleagues do not.

Although earning less than a living wage, having student rather than employee healthcare and facing wage and expectation discrepancies are not new to graduate student workers’ experiences, many cited the COVID-19 pandemic as what pushed them towards unionization.

“The pandemic [has] been a rallying cry for us to come together as graduate students to fight for the respect that we deserve,” Swoboda said. “We deserve to be valued for the work that we’re doing for the University and to stop being exploited as essential workers.”

Correction: A previous version of this article referred to several University statements as coming from University Spokesperson Brian Coy. It has been updated to reflect that those statements were made by University Spokesperson Wes Hester.