中文版请点击此处

After a year of online schooling, the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic loom before children. The inequalities between resources that existed for children of different socioeconomic backgrounds before the pandemic exacerbated transitions to virtual education and may impact children’s educational development for months and years to come.

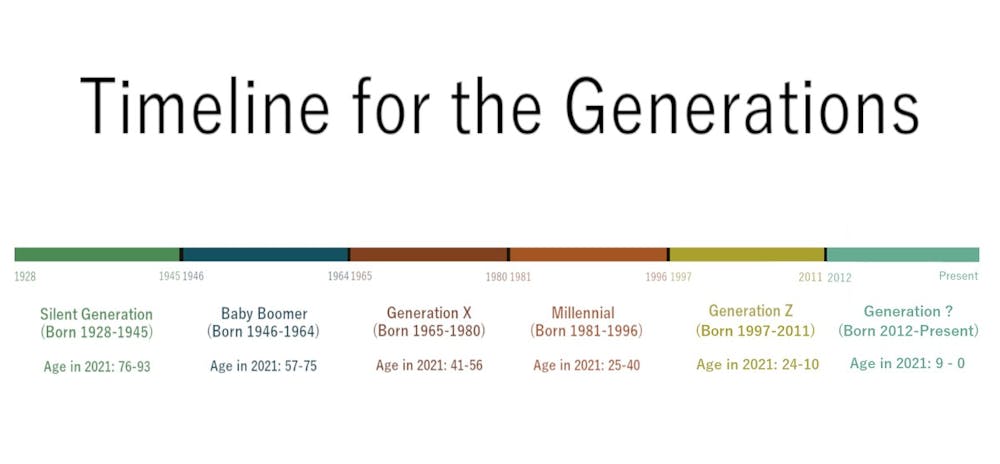

As members of Generation Z — which the Pew Research Center defines as individuals born after 1996 — come into adulthood, demographic researchers turn to define the next generation. Without an official name for the next generation, there is ambiguity over where Generation Z ends and the next one begins. Following the fifteen-year period that identifies Millennials as individuals born between 1981 and 1996, the logical cut off year for Generation Z is 2011, meaning that the older members of this generation are still in early elementary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely the first significant event that members of the newest generation will recall as they age. Similarly, members of Generation Z were around the same age as the children of the newest generation when the recession of 2008 occurred.

Teresa Sullivan, George M. Kaufman Presidential Professor of Sociology and former University president, said she believes that the pandemic-inflicted economic downturn may be more disruptive for children than that of the 2008 recession, however.

After her tenure as University president from 2010 to 2018, Sullivan served as interim provost and executive vice president for academic affairs at Michigan State University, before returning to the University as a sociology department faculty member. Her expertise now specializes in labor force demographics and the sociology of work.

“The recession was really bad for working adults who lost their jobs,” Sullivan said. “The children didn’t have their schooling interrupted … and so that anchor to daily life was there. That’s not there right now.”

Thanks to the pandemic, schools — a key pillar of early childhood development — were transformed overnight. Over the past 16 months, schools have shifted from traditional classes to home-based virtual learning, leading to numerous impacts. According to surveys conducted by the United States Department of Education on grades 4 and 8, 24 percent of all fourth-graders were still participating in remote courses in May 2021, another 24 percent were in a hybrid setting and the remaining 52 percent were attending in person.

From an educational standpoint, teachers and parents have struggled to provide adequate home instruction for children while behind screens.

Commonwealth Prof. of Education Sara Rimm-Kaufman studies the social and psychological experiences of elementary and middle school children. She lamented the academic and social skills gaps that will emerge even when students return to classrooms.

“There’s going to be social and emotional skill gaps,” Rimm-Kaufman said. “They’re missing some emotional skills that they would learn in school like tolerating frustration.”

Rimm-Kaufman also expressed concern for children with special needs and English language learners as they were more likely to fall behind due to limited services available online.

This preludes a larger issue that is plaguing schools across the country — the digital divide, which refers to the lack of access that many children face due to lack of internet at home. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, about 40 percent of lower income parents reported that their children need to rely on public Wi-Fi and an additional 36 percent believe that their children will not be able to complete work due to a lack of computer access. Additionally, numerous districts struggle with funding for personal equipment needed to provide for online learning to all students. There have been efforts to narrow the divide by expanding funding to internet access, but those efforts have not succeeded in eliminating it yet.

Rimm-Kaufman noted that inequities that existed before the pandemic started have grown.

“Kids who had advantages beforehand are often still experiencing many of those advantages during the pandemic,” Rimm-Kaufman said. “Kids who had fewer advantages beforehand are living under more dire and more stressed situations.”

Abiding by social distancing protocol and government recommendations to remain home if a trip outside the home was not necessary, many children lacked exposure to peers and spent much of their time at home.

For children with access to mobile devices, a source of entertainment was streaming service platforms. Such platforms are characterized by their selective on-demand viewing that provides the viewer freedom to choose the content they want to consume. Programs may deliver content in a biased manner, preventing viewers from learning about other perspectives.

Andrea Press, a media studies and sociology professor who studies the impact of media on culture, noted the effect this has on children.

“Scholars find that it leads to a real insular form of accessing information so that we are not exposed to opinions that disagree with convictions we already have,” Press said. “We have a lot of polarization right now on these issues and a part of that is media choice … and children are growing up used to that.”

With the lack of in-person schooling, children cannot meet with those who have backgrounds different from theirs and enrich their knowledge about diverse perspectives.

Additionally, working mothers have had to struggle balancing their careers with taking care of their children due to daycare and school closures.

“We’ve had the largest withdrawal of women from the labor force since the end of World War Two … principally for childcare reasons,” Sullivan said.

The RAND Corporation cited that based on data collected from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, women in the workforce dropped by 2.2 million in October 2020 in comparison to October of the previous year.

Children are watching their parents grapple with changes in different ways based on their socioeconomic status at the start of the pandemic and subsequent changes due to job loss.

“[Children] watched the gendered division of labor in action … maybe it will have a regressive impact on what their vision is of the gender division of labor,” Press said.

There has been growing awareness surrounding the struggles for working mothers as a result of the pandemic — in February, National Public Radio reported that employers offered flexible shifts and relocation to branches closer to home.

Despite the challenges children face in this uncertain time, there is hope that some positives have come out of the pandemic for this generation.

“There’s some good things that come out,” Rimm-Kaufman said. “Some kids are learning attention and organizational skills and self management skills that they never had before.”

Rimm-Kaufman also said she is optimistic that children will overcome challenges caused by the pandemic if given adequate support.

“It is really up to the parents and adults to help kids understand what they’ve just experienced,” Rimm-Kaufman said. “Your kids grow towards health when they’re in contexts and environments that support them.”