During my senior year of high school, I read Toni Morrison’s debut novel “The Bluest Eye.” It presents sexual assault, incest and violence in manners that required me to step away from the book before returning. It’s a hard read — but it’s also one deserving of attention for its powerful spotlight on Black women’s tribulations. As such, I was saddened when my English teacher at the time told me she believed she’d be fired for teaching “The Bluest Eye,” which sat in our school’s storage room of teaching materials. I’m lucky to have read Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God” in high school, a novel addressing similar themes as Morrison’s. Hurston’s book, though, isn’t without its challengers either. Books like these — worthy of study and rich with creativity and commentary — should not sit untouched in storage rooms, kept out of learning spaces.

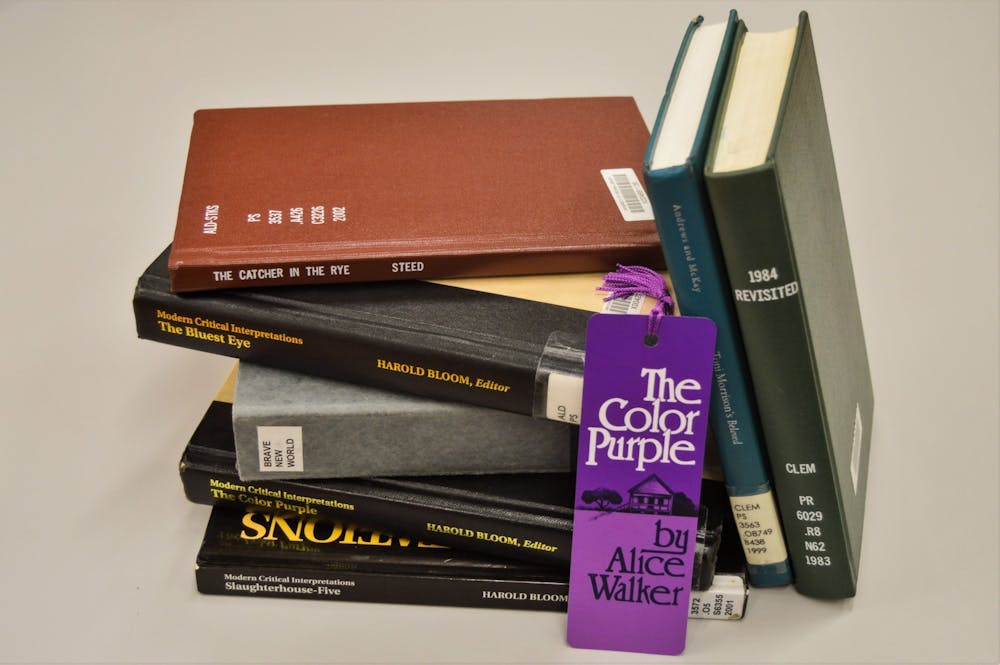

Every fall, Banned Books Week celebrates books that have historically faced challenges and bans in schools, prisons and other social institutions. This necessary celebration allows us to reflect on the works that critics attempt to silence. The most common claims for why a book should be banned include the presence of sex, drugs, violence, confrontation with racial issues, religious violations and blasphemy. Some of these challenged and banned books include Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas. These incredible authors depict violence against marginalized communities — primarily women and Black Americans — to produce creative literary works critiquing patriarchy and racism. They challenge the prejudices that still run rampant in our society. As a result, they often face challenges themselves.

Simply put, these books should not be banned anywhere. Book banning is a form of censorship used purely to preserve certain notions of what people — most often, children and imprisoned people — should think. It upholds a false need for purity at the expense of challenges to racism, sexism, xenophobia and other prejudices. Moreover, it’s completely ignorant to assume that students in high school haven’t already encountered the themes evident in many banned books. Students from marginalized communities routinely face the prejudices that these bans purport to reduce. Reading about them from innovative writers like Morrison, Hurston and Atwood allows students to not only see themselves represented but to also see themselves uplifted.

Book banning in prisons is equally ignorant. Prisons are sites of authority — people in control of other people. Book banning is an authority of censorship that prevents people in prison systems from learning and feeling uplifted through reading. Many books banned in prisons address racial justice in America. These include “The Bluest Eye,” along with Octavia Butler’s “Kindred” — an important piece of literature that uses time travel to send a young Black woman from her home in 1976 to antebellum America. Works by Barack Obama, Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois are also frequently banned in prisons. This trend reflects the disproportionate number of Black Americans in the U.S. prison system, specifically in that it reveals the system’s intent to keep Black Americans incarcerated and silenced.

My point is that book banning often comes with ulterior consequences, if not motives. We should be able to come to our own conclusions on any given issue. This freedom comes with the right to read what we will. Not only does reading allow us to access worlds we may otherwise never see ourselves in, but it’s also scientifically-proven to increase empathy toward others. Works like the ones I’ve mentioned here are not merely displays of violence or assault. They’re also brave promotions of empathy toward the communities who most often get confronted with apathy and hatred.

As such, I ask that you take the time to read a banned book sometime soon. These extensive lists name some of the most challenged books of the past decade and earlier. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that so many of these books feel like mainstays in American and global literature. They persist in spite of challengers — their messages connect to readers far too powerfully to simply fade into oblivion. Certainly, these lists are not without examples of truly problematic books, but by and large, they contain important and beautiful ones. Recognize them, read them and celebrate them. You won’t be disappointed.

Bryce Wyles is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.