It should go without saying that social justice has been on the forefront of the American consciousness since this country’s founding. But just as civil rights and social justice movements have always existed in some capacity, these same movements all suffer from a common ailment — the rewriting of history to fit dominant cultural narratives. Civil rights movements in the United States have had their legacies co-opted by a society that is inherently reluctant to address its deep-seated problems surrounding race and class.

By its very nature, change is uncomfortable. An upheaval of any kind, no matter how small, will cause ripples in the fabric of society. Enter Disneyfication, a process of distortion that sanitizes the past in favor of a cleaner, safer vision of progress. Much like a Walt Disney movie or theme park, Disney-fied history is easy to digest without deeper reflection. Change is plotted on a linear track, and landmark events are reduced to their simplest parts.

In some ways, Disneyfication is a good thing — it makes history consumable for mass audiences who don’t care for the finer details. But history is not meant to be clean, safe or easy. How are we meant to learn from the past when the past itself has been so heavily altered? Disneyfication makes the consumption of social change palatable for individuals who are happy with the status quo and see no reason to disrupt the supposed natural order of things — most often those who benefit from the already existing system.

The Disneyfication of civil rights presents a watered down version of the fight for political equality. It appeals to the public by making radical views more moderate, playing into fairytale-esque tropes and constructing simplified narratives that erase the nuances of political activism. It is an insult to everything these movements have struggled and sacrificed for, and we must work towards spotlighting a more holistic picture of social justice.

Nowhere are the dangers of Disneyfication more apparent than in the remembrance of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. We commemorate and celebrate those who have and continue to pave the way with history lessons in classrooms and federal holidays. But U.S. culture has gradually rewritten the story of civil rights, revolving its narratives around peace and unity rather than radical systemic change and social revolution.

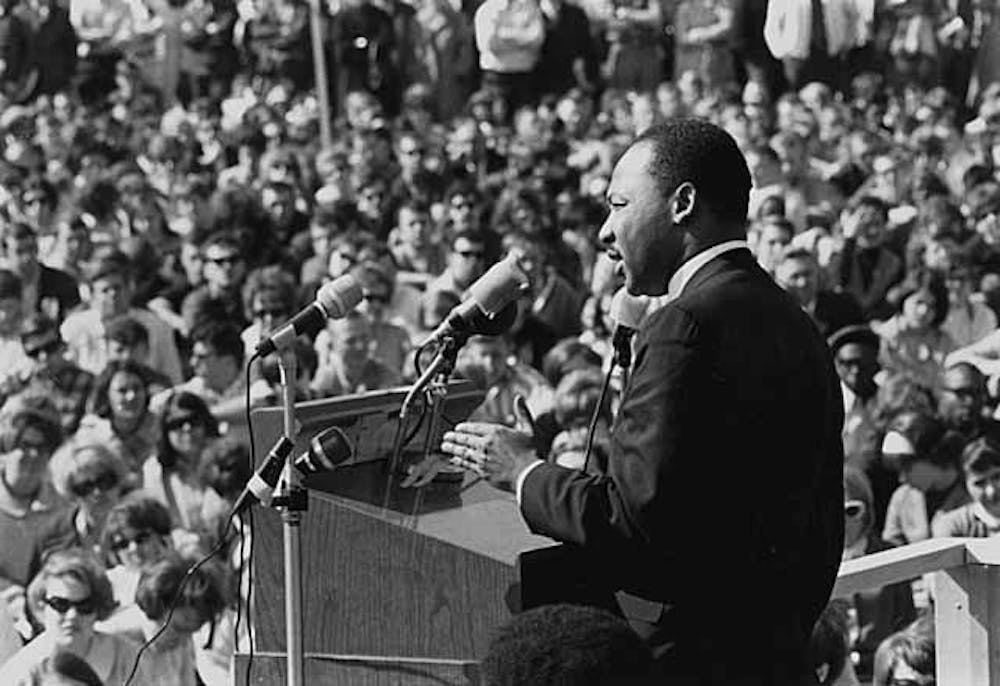

Take none other than the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., regarded as the father of the civil rights movement. In history classrooms across America, King is frequently used to juxtapose political figures in the Black Power movement like Malcolm X. Students are taught that King was a kind man who fought for unity and believed in racial harmony. He is characterized as well-spoken, well-dressed and thoroughly unthreatening. Every year, teachers, politicians and public actors cite King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, cementing him as a prolific speaker who advocated not for a transformation of society but rather an uplifting of its most disenfranchised.

What is not mentioned is that King was far from the moderate that many have dressed him up to be. Rather, he was a revolutionary — in some ways just as critical of American society as the men and women his name is used to denigrate. People are quick to reference the “I Have a Dream” speech but not his vocal opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War or sharp rebuke of the U.S. economic system and its role in perpetuating a cycle of poverty. King was more than a peacemaker. He was a thinker whose writings wrestled with the ideologies of Hegel, Kant and Nietzsche — a man who possessed an acute understanding of the media, the general populace and the court of public opinion.

The Disneyfication of civil rights extends beyond King. The way we remember the Civil Rights Movement often overlooks the calculated decisions that went into swaying hearts and minds. Rosa Parks’ decision not to give up her seat is often thought of as spontaneous — but this obscures her role as a prominent community organizer and the collective efforts to stage this act of defiance. Schools neglect to teach that King, Ralph Abernathy and other activists were extremely conscious of the necessity of news media to stay relevant and worked relentlessly to conform to common media narratives and garner sympathy from white audiences.

Social justice movements have a cascading wave of implications, ranging from expanded political rights for marginalized groups to a better understanding of the impediments imposed on communities of color. And yet there also exists great opposition to even basic acknowledgment of institutionalized inequality in this country — the most recent of which being tensions over Critical Race Theory. Disneyfication is just another way of avoiding confronting conversations about race. For history to not celebrate the work of civil rights activists in its entirety does them a disservice, and it plays into a narrative where social progress is the result of a few key players, rather than a complex network of political coordination.

To frame King and activists like him as accommodating to American society — polite and gentle, messianic yet docile — is to strip them of their intellect, their cunning and their radicalism. These are integral parts of the progressive identity that must be preserved, if only for the future generations that will have to take up its mantle.

Samantha Cynn is a Viewpoint Writer for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.