Lea en español

As a considerable amount of people struggle with mental illness in Virginia and nationwide, depression has become increasingly prevalent on college campuses. As such, it’s increasingly important for students to know how to recognize the signs of depression and best practices for helping their peers cope.

Approximately 1 in 20 adults in Virginia live with a serious mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, while approximately 8 percent of people across the United States experience depression every year.

Comparatively, one in four college-age individuals have a diagnosable mental illness.

Joey Tan, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor from the Department of Family Medicine at the University; Margaret Edwards, program director of Counseling and Wellness Services at the Maxine Platzer Lynn Women’s Center; and Abby Palko, director of the Women’s Center, spoke to the prevalence of depression and mental health concerns in college communities, as well and the importance of caring for others.

Despite the prevalence of mental illness, much of the discussion around depression and other mental health concerns tends to be shrouded by stigma, Tan said.

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot of stigma that still lingers in our communities, in our society more generally, about depression and really mental health concerns in general,” Tan said. “It’s important to continue to normalize that and to really kind of emphasize that this is just part of health, as part of any other kind of health condition that people freely talk about.”

Tan compared depression to withdrawal — a continued detachment from a life one used to be engaged with. Like withdrawal, Tan said depression is characterized by a persistent, chronic low mood and decreased energy along with the feeling of one’s world getting a lot smaller.

While depression and other mental health concerns can affect anyone, historically marginalized populations have exacerbated risk of suffering from depression. LGBTQ+-identifying people, for example, have more than double the rates of mental illness as the general population. Experiencing discrimination makes developing a sense of belonging much more difficult, and Edwards said having a sense of belonging is a protective factor against depression and other mental health concerns — particularly during one’s college years.

“Identity formation and relationships are the two great developmental tasks of early adulthood,” Edwards said in an email statement to The Cavalier Daily. “It makes sense that when someone has intersecting identities that have been rejected in society historically, these developmental tasks are harder to navigate.”

In addition to struggling with mental health concerns, many individuals have difficulty accessing care. More than half of the people in the country who have a mental health condition did not receive any treatment last year, Tan noted.

The lack of racial and cultural diversity among professional therapists hinders students’ sense of connection when they seek counseling services. In 2019, 83 percent of the U.S. psychology workforce was white, 70 percent was female and 95 percent was without disabilities.

Palko explained this traces back to the accessibility and selection during professional training.

“The unfortunate fact is that the mental health professions are still overwhelmingly staffed by white, middle-class women,” Palko said. “Schools that train therapists should be paying attention to that and doing their best to recruit a diverse pool of applicants to turn into a diverse pool of counselors.”

Palko further pointed out that counselors are trained to facilitate a therapeutic relationship inclusive of any identity. In some cases, however, having a similar identity helps those receiving care build trust with providers more easily.

“The identity pieces fall to the side as you dig into what the issues are that brought you there,” Palko said. “Having someone who has a lived experience that mirrors yours is really helpful — you don’t have to explain the importance of things … you can just dig in.”

Tan said one of the important things that students can do to support peers with depression is to offer suggestions in seeking professional help.

Palko pointed out that counseling services are free of charge for students at the University. Services such as individual or group therapy, psychiatric services, drop-in consultations, referral to other professionals, and emergency services can be accessed by contacting the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services online or by phone.

Some students, such as the Young Democratic Socialists of America at U.Va., are advocating for CAPS to create a larger staff of more diverse professionals to increase access to quality mental health services on Grounds.

Palko explained that the University works to make sure that students are able address barriers to care such as the ability to pay for services, transportation, navigating insurance and accessing the various resources that the University offers. Recently, the University rolled out TimelyCare at the beginning of October, which gives students free and ready access to 24/7 mental healthcare counseling without requiring insurance.

Besides directing peers to professional care, there are other ways students can be supportive and helpful for people who are depressed. Peers can provide a listening ear and emphasize that people with depression are not facing these challenges alone, Tan added. This includes encouraging peers to engage with the world, offering to spend time together and generally supporting them to not withdraw completely from normal activities.

“Resist the urge to go into problem-solving mode,” Tan said. “Make sure that you’re able to acknowledge the person’s experience, keep that in the center, and normalize what they’re sharing without minimizing it.”

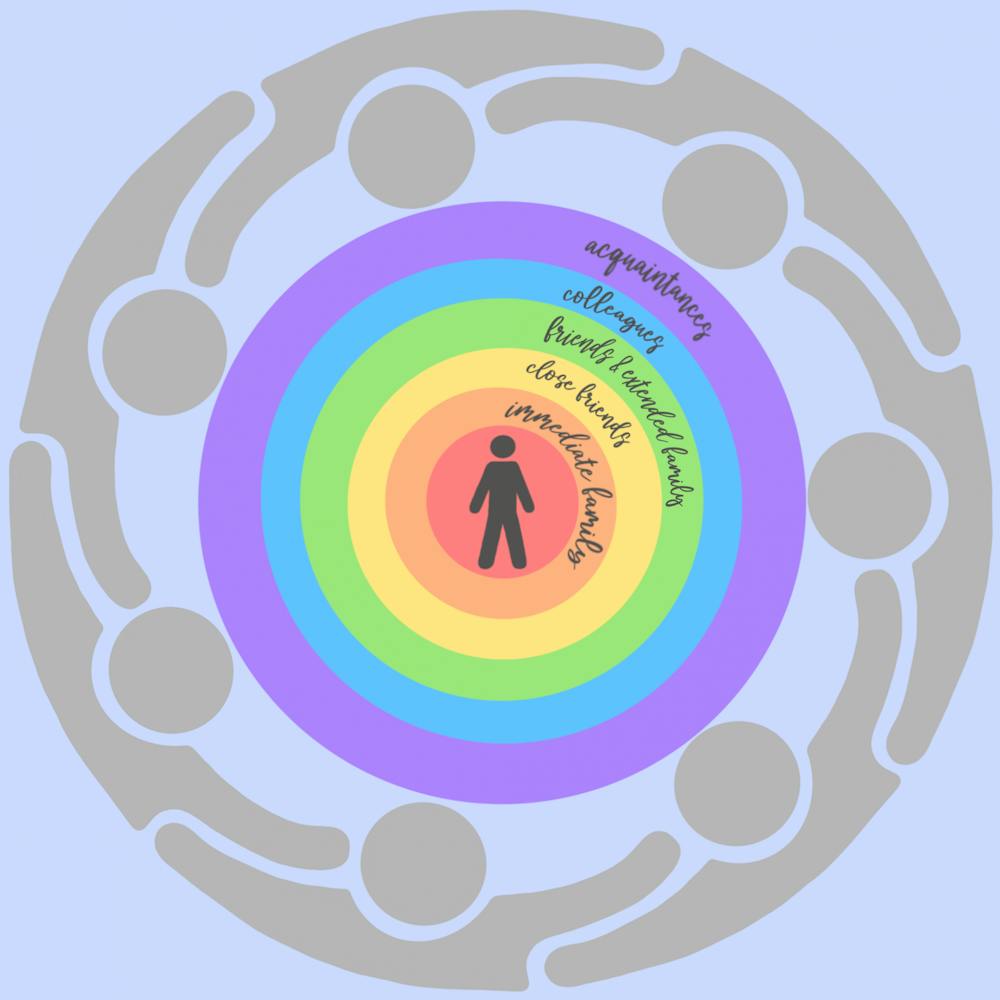

Intimately related to the discussion of supporting peers with depression is community care. Palko defined self and community care in terms of ring theory, which represents the person experiencing a crisis is at the center of a series of concentric rings representing one’s social circle. Closest to the center are the person’s immediate family and friends, and then as the circles get larger, the relationships get more distant.

“The concept is you always support in and you always dump out,” Palko said. “You get support from people who are less impacted by the issue, and you support people who are more impacted by it. And that’s how we have a web of community care.”

The issue of depression in college environments is multi-layered, still shrouded by social stigma and sometimes exacerbated by historical marginalization. As suggested by experts, peers can be supportive by encouraging those with depression to maintain networks of community care.