In a July press statement, the State Department called on China to “abide by its obligations under international law” per the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling against China’s sweeping South China Sea claims. The press statement rebuked China for shirking “the rules-based maritime order that respects the rights of all countries, big and small.”

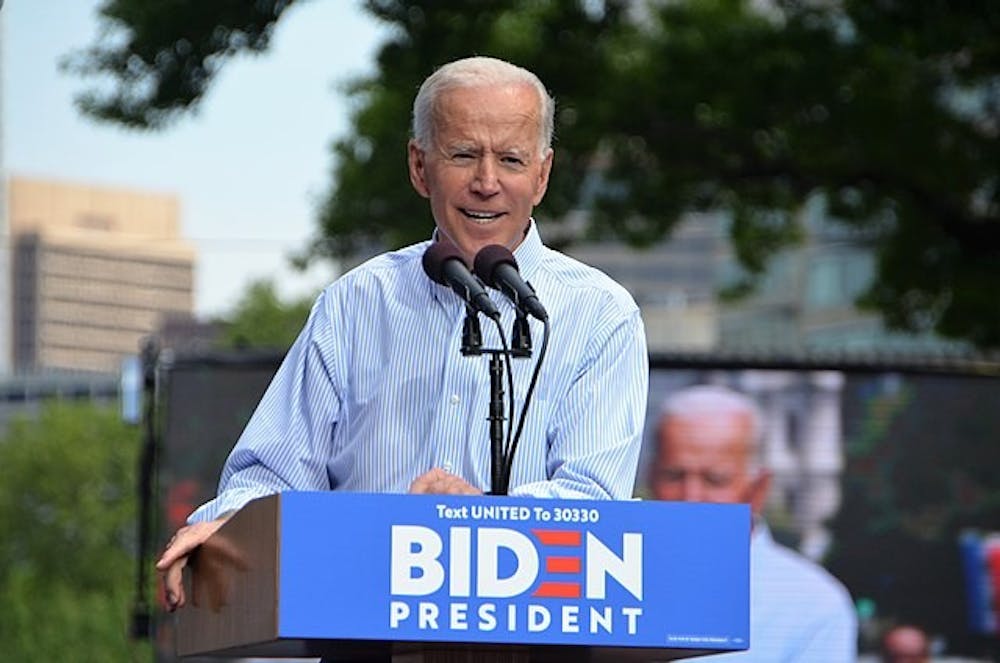

However, such appeals to rules-based order now ring hollow as the Biden administration’s stance on the sovereignty dispute between the United Kingdom and Mauritius over the Chagos Archipelago. In August, the State Department told the Washington Post the United States “unequivocally supports U.K. sovereignty,” running roughshod over the numerous multilateral institutions urging the U.K. to decolonize the archipelago.

The administration’s double standard is attributable to the fact that the U.K. currently leases the Chagossian island of Diego Garcia to the U.S. free of charge, allowing the Pentagon to operate a secretive military base there. The U.S. has historically rejected claims of Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos, as a new landlord could cast uncertainty over the future of this base by charging rent or resettling the indigenous Chagossians — a group forcibly removed from the archipelago roughly fifty years ago.

Washington first set its sights on the Chagos for its strategic location during the mid-1960s. Accordingly, the U.K. annexed the archipelago from Mauritius and declared it a British Indian Ocean Territory. This prompted the United Nations General Assembly to declare that attempts to detach islands from Mauritius “for the purpose of establishing a military base” would contravene international law.

Nonetheless, in a surreptitious quid pro quo the following year, the U.K. agreed to expel the Chagossians and lease Diego Garcia to the U.S. in exchange for a $14 million discount on the Polaris Nuclear Program. The U.K. would have difficulty upholding its half of the deal, however, if the Chagossians — whose history on the island dated back two centuries — were accurately regarded as permanent inhabitants with democratic rights. So, to the public, press and UN, the Anglo-American governments held that the Chagos was solely inhabited by itinerant Mauritian laborers.

Thereby averting international scrutiny, the U.K. expelled roughly 2,000 Chagossians between 1968 and 1973. First, the plantations on which many of their livelihoods depended were shut down, those who had traveled to Mauritius were prohibited from returning home, and the amount of food and medicine coming into the Chagos was restricted. The islanders watched as soldiers killed their pets in gas chambers. Those who remained were forcibly deported to Mauritius and the Seychelles via cargo ship. Two years after the last Chagossians were removed, the U.S. Navy — seeking to secure funding for a military installation — could tell Congress that Diego Garcia was an “unpopulated speck of land.” Meanwhile, the dispossessed Chagossians faced poverty and discrimination in unfamiliar territory.

More than five decades later, Mauritius still maintains its territorial claim over the Chagos, with the dispossessed Chagossians continuously fighting legal battles for the right of return. In 2015, the International Court of Justice buttressed the Mauritian and Chagossian cause, advising the U.K. to end its “wrongful” administration of the Chagos and return it to Mauritius “as rapidly as possible.” Other multilateral institutions concur that the BIOT rightfully belongs to Mauritius, such as the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the African Union and the UN General Assembly — the latter of which demanded that the U.K. withdraw from Mauritius by Nov. 2019.

Still, the U.K., with support from the U.S., remains intransigent in its refusal to comply with international law until the archipelago is not needed for defense purposes. How soon this will be is hard to say, however, as Diego Garcia has proven to be strategically crucial for the U.S. military. For example, during the War on Terror, it served as a launching point for attacks on Afghanistan and Iraq and, according to Bush administration official Lawrence Wilkerson, as a “transit location” for the CIA’s “nefarious activities.”

The Biden administration’s disregard for international law with respect to the Chagos undermines its stance on the South China Sea, giving the impression that the U.S. defers to international law only when it does not impact U.S. military interests. Until Washington changes its stance on the Chagos sovereignty dispute, the U.S. will be complicit in the U.K.’s illegal administration of the archipelago and the displaced Chagossians will be barred from returning home. On top of that, American appeals to “rules-based” order will be weakened by this hypocritical dismissal of international law.

Robert McCoy is an Opinion Columnist at The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.