Electric cars are becoming the vehicle of the 21st century as governments push to reach global climate goals and auto manufacturers pledge to introduce pure electric models, whose numbers are predicted to reach 145 million by 2030. In order to meet this increasing demand, the University’s Multifunctional Thin Film Research Group is seeking to address prominent problems with the current industry-wide electric car battery model, which does not charge efficiently and contains a flammable liquid that puts drivers and emergency responders at risk if the car becomes compromised.

The team is led by Jon Ihlefeld, associate professor of materials science and engineering and electrical and computer engineering, and is supported by a National Science Foundation grant. Their proposal addresses the electric car battery problem by focusing on including ion-conducting ceramics rather than the liquid electrolyte of a lithium-ion battery.

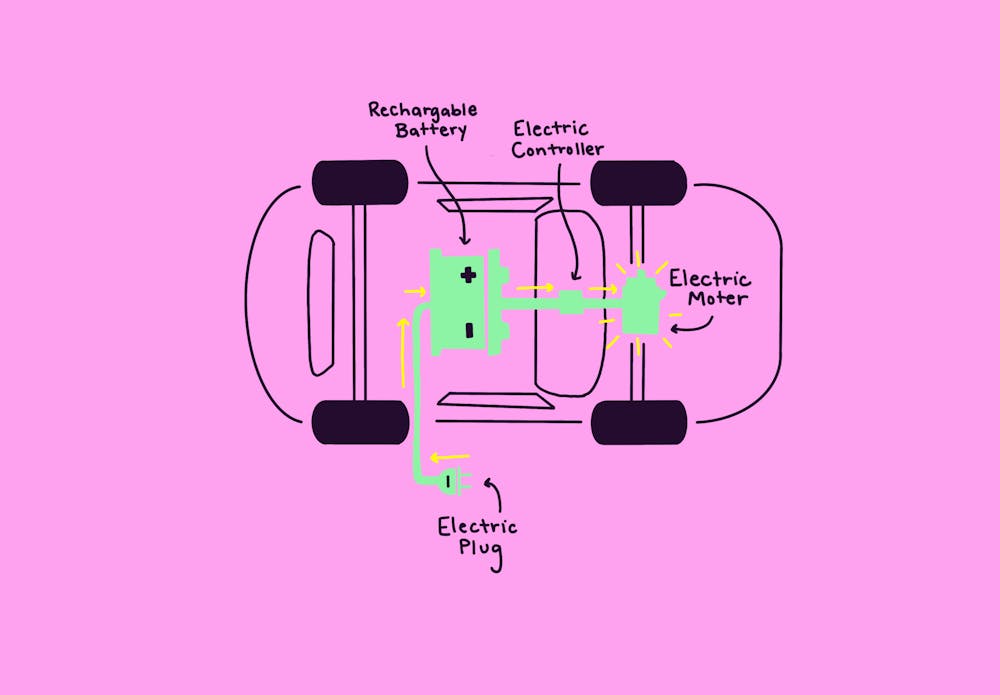

The classic lithium ion battery is made of a lithium ion phosphate cathode and a carbon anode with liquid electrolyte separating the two nodes. When charging or discharging, the lithium ion travels from one electrode to another with an electron on another circuit following it to balance the positive lithium ion’s charge.

“[These batteries] have very low power so they can store energy, but they can’t discharge that energy very quickly,” Ihlefeld said. “So if you needed to do a function on your device that consumed a lot of energy in a very short period of time, these batteries were insufficient.”

Given the inefficient charging of the current batteries, and the flammable electrolyte within, Ihlefeld began to investigate the use of ion-conducting ceramic material instead of liquid electrolyte within the battery.

“What we are proposing to do, is to take away that polymer in a liquid electrolyte and put our ceramic material in there,” Ihlefeld said. “So the general components [will remain] the same, we still have a cathode and anode, we've just now replaced that flammable liquid electrolyte with a ceramic oxide material.”

Ian Brummell, a doctoral student at the U.Va. School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, is another lead member of the research project — who connected with Ihlefeld at Sandia National Laboratories while Ihlefeld was recruiting graduate students before moving to work at the University.

“I met him knowing that I was planning to go to grad school,” Brummell said. “We sort of talked through projects, and this was one of his ideas at the time, and I said, ‘Sign me up to that one.’”

The project is currently developing techniques to measure the intricacies of the ceramic material, in order to ascertain the best use and structure of it within the battery. They plan to monopolize the current battery model keeping the mechanism between the anode and cathode the same while replacing the material within to increase its efficiency.

“What we're trying to do is minimize or eliminate the features within it that add resistance to its charging process,” Ihlefeld said.

By teasing apart the materials and structure of the battery, they intend to investigate and measure each defect in order to create a library to determine which can be tolerated and which need to be corrected within the ideal battery model.

Brummell’s end goal for his doctorate is to show off the methods they are producing and gather a set of data that can illuminate the fundamentals behind the electric car battery – which is currently considered one of the major blocks to transitioning to electric cars.

“The next big battery innovation is going to be a huge step for probably everything we do because we rely so much on mobile technology,” Brummell said.

If they are successful and auto manufacturers start making batteries with their design, it could potentially help overcome some of the challenges of working towards a carbon-neutral society.

“We could enable a future where people are less hesitant to invest in an electric vehicle,” Ihlefeld said.