It is evident now more than ever that words hurt. The right word — and thus, the wrong word — can resurface after years and dictate how people view the person who said it. Throughout history, different words have been discarded as offensive, insufficient or just replaced for the way that they are pronounced. However, some words continue to return to our collective vocabulary for all of the wrong reasons.

Reclaiming words is defined as “the phenomenon of an oppressed group repurposing language to its own ends.” One of the most widely accepted examples of reclamation is “queer,” even being added to the acronym for different sexualities. One of the main reasons that “queer” has been successfully reclaimed by members of that community — unlike other slurs — is because its usage is inclusive. This has made using the word “queer” far more effective in aspects of gender and sexual equality than, for instance, the n-word in racial equality.

The n-word and slurs like it associated with Black people can either be said by anyone, or everyone can stop saying them. Neither of these options are ideal. Nevertheless, the path forward is clear — everyone needs to stop saying it. Words matter drastically. People can get fired, threatened, assaulted or shunned for words because individuality is an American ideal that we actually wholeheartedly support. So, the n-word must go as a whole. This may be completely unrealistic, but even if it is never achieved, perhaps I can at least change someone’s mind about using it.

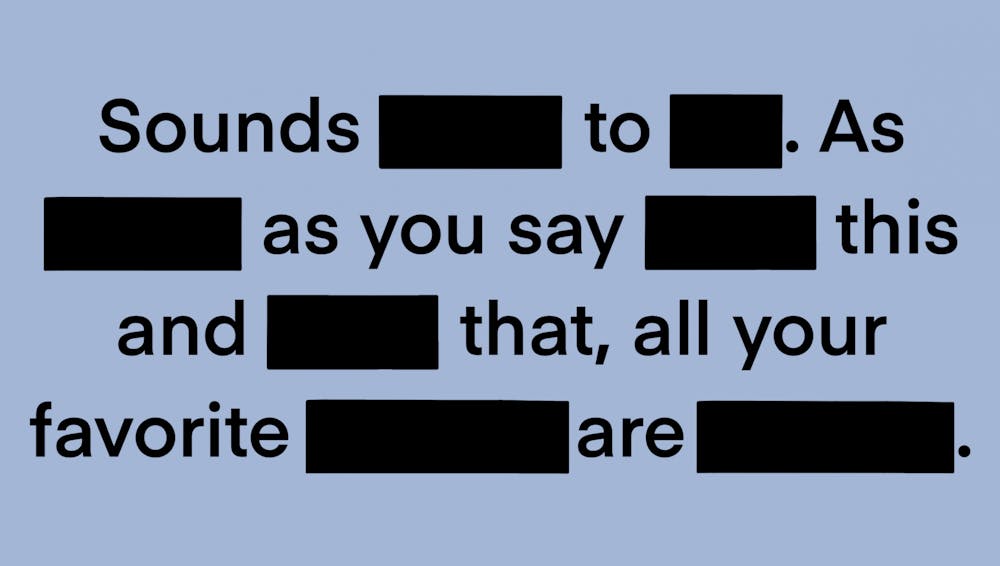

The justification for using certain, more controversial slurs is that the oppressed group has redefined it to mean something else. Today, some might argue that the n-word no longer means ignorant or subhuman, but that it means a friend, someone close or just a random person. The problem with this justification is the meaning of a word cannot change erratically. The n-word cannot mean one thing when one person says the n-word and another thing when it is someone else. If that is the case, no one will ever be able to agree on how the word is actually being used — and moreover, if it is being abused or taken advantage of.

If this word was truly progressive, liberating or helpful, it would be inclusive. One of the reasons “queer” has been widely accepted by the LGBTQ+ community as well as outsiders is because its reclamation succeeded at three levels. First, individual members of the community accepted it, then the majority of the community accepted it and finally, knowing that it could no longer be used as a weapon, those outside of the community accepted its rebranding as a positive, self-identifying word instead of an insult. Essentially, the power of the slur was taken away, and so it ceased to be a slur.

That being said, the successful reclamation of “queer” can also be attributed to its history of being less complex and ingrained — both within and outside of the LGBTQ+ community — than the n-word’s history as both a slur and an attempted point of reclamation. The problem with the n-word is that this power is still there. Therefore, even if one is Black, they are essentially still calling themselves a slur. They may not take offense because they have individually redefined it, but this has not been agreed upon as a whole by the Black community. We will never ever accomplish the last level of reclamation if the n-word has not proceeded past these first two.

Therefore, the problem is not only that it is not agreed upon to what the new definition is, but also that the new definition is exclusive. What is the point of reclaiming a word if the very group of people you want to verbally disarm has not been disarmed? It still hurts if a white person were to use that word, and so the power is still there. Finally, what does policing the slur even solve? When the question of the n-word and its use surfaces, it is more about having a leg up verbally over white people than actually solving anything. It is more about Black people having the privilege to say it and to call themselves it without much consequence, while a white person or a non-Black person may be labeled negatively or socially shunned. That is not the sort of privilege that helps anyone. I’d much rather have economic equity for Black-owned businesses, be taught African history in primary school and statistically have equal opportunities than own the privilege of freely saying a slur. The same can be said for offensive words created for women. Are we willing to reach the third level of reclamation as a society? Probably not.

We should simply get rid of the word. Using the n-word brings no sort of social, economic, or political progress. As stated above, reclamation is the repurposing of a word to meet the group’s ends. What ends have we met by using these words? What have we gained? If anything, we’ve only opened more conversations about cancellation, identity and appropriation instead of conversations about financial equity and history. Are such words that have maintained their hateful roots worth keeping? No. The first step to forming a future is to learn from history, not to emulate it.

Shaleah Tolliver is the Senior Associate Opinion Editor for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.