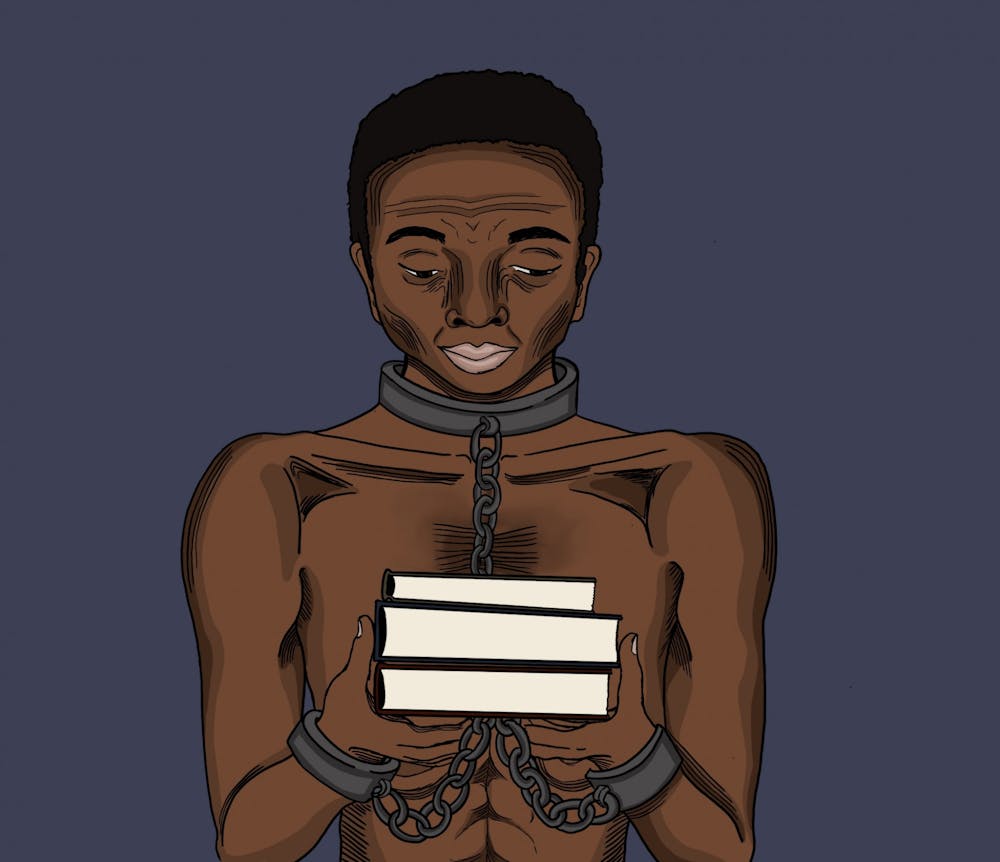

As an English minor here at the University, I have encountered a number of different genres of literature in my classes. My least favorite is the slave narrative — an account of the life of an enslaved through their perspective. While I agree it is imperative to expose non-Black students to the harsh realities of this genre, I find it incredibly damaging for myself as a Black student. To give an example, I am currently taking History of Literatures in English II and have enjoyed it thus far. However, when it came time to read “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” I could not get through the first few sections. The content was wonderfully honest, but graphic — and I could not stomach it.

Here at the University, many English professors make an effort to include Black authors. In the class I currently take, my professors have described slave narratives as vital to understanding the full scope of American literature. I agree wholeheartedly. Firsthand accounts of the experiences of enslaved people on plantations and in cities are vital to comprehending the lives of the four million people enslaved throughout American history. That being said, the degree at which English professors at the University include slave narratives gives me the same feeling I get from trauma-porn. I know the harsh realities of my ancestors — not to mention the reality of enslavement on Grounds — and to have it thrown in my face quite carelessly is jolting every time. It is fantastic that Black authors are included in these classes, but to only include slave narratives is the bare minimum. And to be grateful for the bare minimum is tragic.

I have stated previously that I do not believe white people should teach Black history. That is true in this situation as well — white people should not be teaching slave narratives. The level of empathy needed to adequately teach Black history has been lacking from what I have observed in my English courses that are taught by white professors. Their warnings of sensitive language are nice, but not when that sensitive language includes words such as “negro.” I believe there are two sides to this particular part of the issue. There are non-Black professors who give ample warning, but still teach material inadequately, and there are non-Black professors who give no warning and still teach the material inadequately. The students who then make ignorant comments regarding the literature in the discussion sections to follow are a whole issue in and of themselves.

So far in my coursework, I have had to read the work of writers such as Phillis Wheatley, who showed deep appreciation for her enslavement, and Frederick Douglass, who wrote graphically about his experiences while enslaved. Are there many Black authors in history that wrote in the English language about topics other than enslavement? The answer is yes — there are. Yet, taking an English history class at the University would have you think otherwise. It can be dangerous to only show the perspectives deemed as worthy. As college students we should have the common sense to know that self-education is just as important as what we learn in classes. However, for many students, it can be easy to be disinterested in the things that affect students of color the most. In these cases the classroom is the only place white students would learn about these issues.

In my African American Studies and Creative Writing courses — which also have heavy reading requirements — I have had the opportunity to read a broader scope of works by Black authors that span multiple genres. I wish I could say the same for my History of Literature in English courses. Many of the enslaved authors the English professors include in the curriculum have works about topics other than enslavement, but this still remains the focus. There is a larger array of themes Black authors have written about other than violence and trauma. In addition, there is also a tendency to teach only the most popular names in Black literary history. I feel that if I were to ask many students in my classes to name more than three Black authors their answers would be limited to the likes of Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Phillis Wheatley, Frederick Douglass and Maya Angelou. All of these writers were and are fantastic, but there is a much broader scope to what Black American authors in history have to offer.

There are a multitude of solutions for these issues. The simplest would be to expand curriculum. Begin including literature such as “The Einstein Intersection” by Samuel R. Delany, “Revolutionary Petunias” by Alice Walker and “The Walls of Jericho” by Rudolph Fisher. Begin to swap out traumatic slave narratives for stories about Black joy, romance, existentialism and satire. Begin inviting Black guest lecturers to handle the heavier topics of trauma and violence against Black people. Begin spending less time on white writers and more time on writers of color in general.

I am still overstimulated from the increase in racial tensions and media exposure of racial conflict ever since the death of George Floyd almost two years ago. It is not easy to exist as a Black person in a majority-white space like the University while continuing to face the harsh realities of being Black in America generally. Black history in America may start with slavery, but it does not end with slavery. If a class is titled Histories of Literature in English, the Black authors featured should not primarily feature those who wrote about enslavement. When I became an English minor, I did not expect to have these stories shoved down my throat repeatedly. Slave narratives should still be featured in class curriculums, but they should not be the focus when it comes to Black authors.

Aliyah D. White is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.