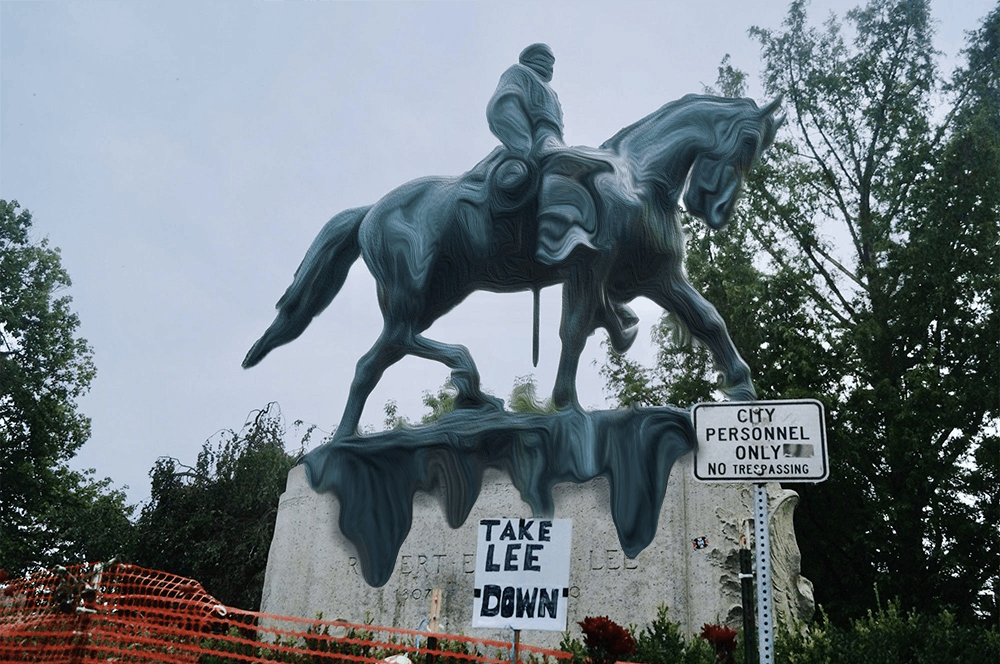

Nearly four years after the violence of the “Unite the Right” rally, Charlottesville City Council removed the Robert E. Lee statue standing in the center of Charlottesville’s Emancipation Park — now, the community grapples with the question of what should become of those 1,100 pounds of bronze.

Council approved the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center’s “Swords into Plowshares” proposal to melt the piece down and create a new piece of art with the metal last December. JSAAHC began in 1865 and continues today as a center for Black heritage.

As was the case with the 73 Confederate monuments removed or renamed in cities across the South in 2021, Charlottesville now faces the endeavor of replacing the statue with a structure that both contends with the racism of the past and represents a new path forward.

The statue of Lee, former commander of the Confederate Army, was erected in 1924 after being gifted to the city by Paul McIntire, prominent philanthropist and namesake of the University’s McIntire School of Commerce, McIntire Amphitheater and McIntire Department of Art. Designed by both American artist Henry Merwin Shrady and Italian sculptor Leo Lentelli, the bronze piece featured the general riding triumphantly on horseback. Confederate veterans reunited for the statue’s unveiling, which also featured a speech by University president Edwin Alderman.

Following years of litigation and advocacy efforts by community members and students — including petition by current fourth-year College student Zyahna Bryant — the Virginia Supreme Court approved the statue’s removal in April 2021, ruling that monuments of Confederate leaders are not protected by state law. The City removed the Lee statue July 10 of the same year.

In the wake of the piece’s removal, the City faced a new question — what would become of the statue itself?

After considering six different proposals, Council chose the JSAAHC’s plan to melt down the monument, using the raw materials to create a new piece of art.

The project — entitled “Swords into Plowshares” — aims to gather community input in order to design a piece that represents the current beliefs and needs of the city itself.

Prof. Jalane Schmidt, ambassador of the project and director of the University’s Memory Project, contrasted the planning process with that of the original Lee statue.

The Memory Project is an initiative that combines interdisciplinary fields with the goal to “examine how we think about the past and how we use it to shape the future,” according to the group’s website.

“It's up to the community to decide … because it's the opposite of what happened 200 years ago,” Schmidt said. “We would like, going forward, for this community to be known for having democratic processes inform our public spaces and the art that goes in them.”

After reviewing feedback, JSAAHC hopes to select an artist for the project by 2024.

The JSAAHC plan is not without its challenges. The City currently faces a lawsuit filed by a plantation museum and a Civil War battlefield who want to have the statue repurposed as a Civil War cannon instead of ceding control to JSAAHC. When asked about the suit, Schmidt simply said that this response is what happens when you “poke the bear.”

Community organizer Kendall King, curator of an exhibit in the University’s Special Collections Library entitled “No Unity without Justice,” emphasized the importance of art in community-building five years after the rally occurred. King was one of the counter protestors who locked arms with one another around the Jefferson statue on the North side of the Rotunda when white supremacists marched through Grounds the night of Aug. 11, 2017.

“I just hope that it incentivizes people and students to come together and to keep that momentum behind movement and community building,” King said.

Following the end of the Civil War, proponents of the “Lost Cause” ideology constructed hundreds of similar public works honoring Confederate leaders. The Lost Cause ideology attempts to frame the South in a positive light, celebrating the antebellum South and serving as a foundation for racial violence.

In the Confederacy’s former capital of Richmond, an enormous statue of Lee on horseback was unveiled in 1890 before a crowd of more than 100,000 people. Later in 1907, the city also honored Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart with a 22-foot bronze statue.

In 2012, Charlottesville City Council Member Kristen Szakos served as one of the first voices in Charlottesville to publicly question the presence of Confederate statues in the city.

Szakos’ considerations elicited harsh backlash from many community members, including death threats.

“I felt like I had put a stick in the ground, and kind of ugly stuff bubbled up from it,” Szakos said in a statement to the New York Times.

Despite public opposition from proponents who argued that the Lee statue holds historical value, Charlottesville city council created a Blue Ribbon Commision on Race, Memorials and Public Spaces in 2016. The Commission served as an advisory group tasked with examining and providing a recommendation on the relocation or transformation of the Lee statue. The council then voted to remove the piece — a decision that prompted a court case from a group of Charlottesville residents over whether the city had the right to do so.

In the midst of legal proceedings, the events of Aug. 11 and 12 of 2017 sparked national debate over the Lee statue’s future. White supremacists gathered at the University Aug. 11 brandishing torches and shouting racist, anti-Semetic and homophobic chants to protest the removal of the Lee statue from Emancipation Park. The next day, the “Unite the Right” protest turned violent, and white supremacist James Fields drove a car through a crowd of counter protesters — injuring 19 and killing Charlottesville local Heather Heyer.

Schmidt cited Heyer’s death as a major turning point in the public’s opinion of the Lee statue.

“People who had formerly not been as educated about the issue or maybe kind of passively favored keeping [the statue] or thought ‘what's the big deal?’ or whatever, the scales kind of fell from their eyes,” Schmidt said. “They could just see that this [statue] is something that really draws in white supremacist elements.”

As for the Lee statue itself, King has heard a number of interesting proposals for the melted bronze. She mentioned proposals for art as abstract as bronze blobs to a more practical 24/7 publicly-accessible restroom or even a children’s playground.

To King, the most important criteria for the project is that the bronze’s new form serves the community.

“Using that bronze specifically to transfer it into civic things that are welcoming, that are acceptable and that are good for kids and adults alike — like things that really get people to, like, spend healthy, constructive positive time together in a public space — I think would be a really cool way for this project to manifest,” King said.

Whatever may become of those thousand-plus pounds of bronze, Romero hopes that a community with such a heavy history can find levity in art.

“Now it's time for a lot of us to find justice and healing through art,” Romero said. “And it's not our job to preserve anything anymore. It is now our job to continue to tear it down and to find ways to heal through our art institute in a way that brings in multiple generations and people of all ages and all walks of life.”

As part of her mission for more informed art, Schmidt — alongside community members Kendall King, Natalie Romero and Hannah-Russell-Hunter — also curated an exhibit in the University’s Special Collections Library entitled “No Unity without Justice.” The exhibit features the work of students and Charlottesville racial justice activists who organized demonstrations and events in response to the “Unite the Right” rally and will run through Oct. 29.