From May Days protests to disputes over former president Frank Hereford’s membership in the racially-exclusive country club Farmington to the occupation of Carr’s Hill, student activism at the University was alive and well during the 1970s.

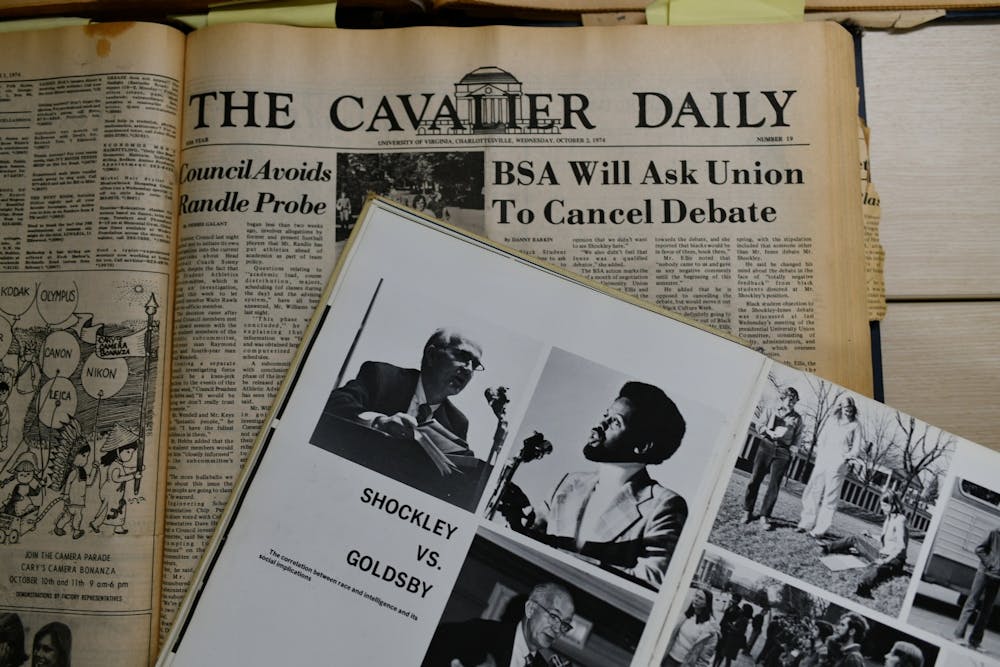

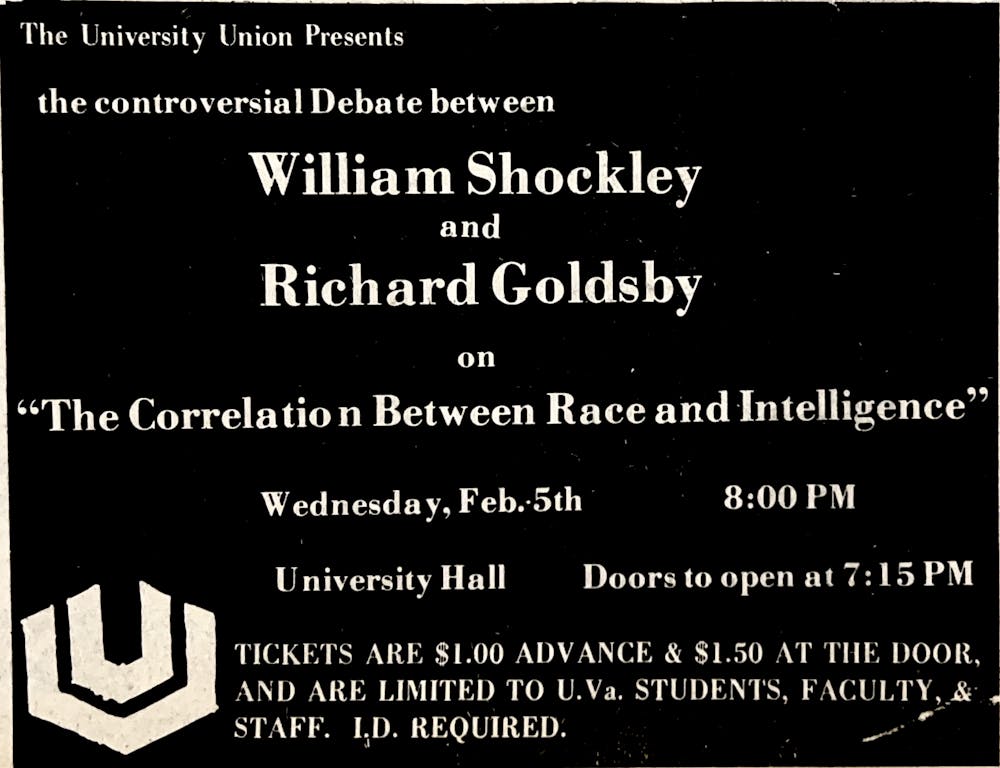

One such newsworthy event — spawning a number of letters to the editor and articles — was the decision to host a debate titled “The Correlation Between Race and Intelligence” featuring prominent eugenics supporter William Shockley during the 1974-75 academic year.

And at the center of this controversy — recent Board of Visitors appointee Bert Ellis.

When he was invited to visit the University in 1974, Shockley’s former accomplishments as a Nobel Prize-winning physicist had already been overshadowed by his dedication to eugenic theories, turning him into an outcast in the academic community. Shockley did not have training in genetics, biology or psychology — a white nationalist, he dedicated decades in an attempt to prove that Black Americans suffered from “retrogressive evolution.”

“He went from being a physicist with impeccable academic credentials to amateur geneticist, becoming a lightning rod whose views sparked campus demonstrations and a cascade of calumny,” an LA Times obituary of Shockley reads.

No stranger to controversy, debates featuring Shockley had already been attempted at Harvard, Yale and Princeton before news broke of the planned debate at the University. Events with Shockley at Harvard and Yale were canceled following student protests.

“Shockley's theories represent a much greater threat to people's freedom than the refusal of a platform,” a Harvard Crimson article dated from 1973 reads.

This came at a time when U.Va. was seeing significant change to its student body — the University had only become fully coeducational in 1970 when 450 women entered the first-year class. The school had also just fully integrated in the 1960s, though Black enrollment remained low.

Class of 1976 alumnus Paul Freeman was Student Council president during the 1975-76 academic year when over 300 students occupied Hereford’s home in protest of his behavior. Freeman described the state of race relations throughout his time at the University as “dismal,” adding that there existed a tension between those who were nostalgic for a time before women and students of color were permitted to attend.

“Race was an emotionally-charged issue,” Freeman said in an interview with The Cavalier Daily, adding that the Shockley debate “part of the whole mileu.”

Class of 1977 alumna Marjorie Leedy Green was news editor for The Cavalier Daily when the Shockley controversy took place. Less than two years later, she would become the first woman to serve as editor-in-chief.

Green remarked that the Shockley debate became one of the “standout features” of her time on The Cavalier Daily and at the University, but like Freeman, added that larger tensions over race formed a backdrop to the event.

“There was just a lot of discomfort and that built to anger, I'd say, in part because of the Shockley invitation, but ultimately, months later, there was the confrontation on Carr’s Hill with President Hereford,” Green said.

In October 1975, more than 300 students rushed Carr’s Hill after Freeman adjourned a Student Council Open Forum on Minority Affairs because Hereford had been spotted at “The Threepenny Opera” rather than attending the forum.

More than a year earlier, Shockley had been invited to the University by the University Union — a now-extinct student-run organization responsible for putting on concerts, speakers and debate-style events subsidized by student activity fees and ticket sales, similar to the operations of the University Programs Council today.

During his time at the University, Ellis led the Union as tri-chairman and spokesman. Today, he is a businessman and president of the alumni group the Jefferson Council.

“The Union is the predominant body on the Grounds charged with providing a social life for the University to complement the academic life,” Ellis wrote in 1975.

Today, Ellis’ recent appointment to the Board of Visitors by Governor Glenn Youngkin has been met with pushback. Student Council called for Ellis’ resignation in an Executive Board statement last month, citing an incident in 2020 following controversy over signage on Lawn room doors that criticized the University's history of inaccessibility and enslavement. Per a personal statement, Ellis was “prepared to use a small razor blade” to remove part of one sign before two University ambassadors explained this would be considered “malicious damage” and asked him to leave.

As a member of the Board, Ellis joins 16 other individuals in overseeing the University’s long-term planning, health system, budget and College at Wise, among other responsibilities. Ellis sits on the Academic and Student Life Committee, Advancement Committee and Buildings and Grounds Committee.

Neither Ellis nor Youngkin responded to a request for comment for this article.

Disputes over Shockley’s impending visit first began to surface in Oct. 1974, when the Black Student Alliance voted to urge the Union to cancel the debate. Ellis explained the Union had scheduled the event during Black Culture Week in order to "draw white attention" to the week — leadership in BSA, though, said this was not the purpose of the week in the first place.

“We don’t wish to have large numbers [of whites] take part in our activities,” BSA vice chairman Linda Quarles told The Cavalier Daily in an article dated Oct. 9, 1974.

At the time, Ellis told The Cavalier Daily that he made an effort to check in with Minority Culture Committee Co-Chair Sheila Crider, who was responsible for obtaining “the Black opinion.” Per documents obtained by The Cavalier Daily through Special Collections, the Minority Culture Committee was a committee created by Ellis and his tri-chairmen that replaced the Union’s previous Black Culture Committee. The group’s main responsibility was putting on Black Culture Week, as well as educating the rest of the University to “their cultures, interests and lifestyles.”

“Nobody came to us and gave us negative comments until the beginning of the semester,” Ellis said at the time.

Throughout repeated interviews with The Cavalier Daily, Crider vehemently opposed Ellis’ characterization of the events.

“Shockley is an insult to our intelligence,” Crider told The Cavalier Daily for an article dated Oct. 2, 1974. “And as a representative of the Black community, I expressed my opinion that we didn’t want to see Shockley here.”

Ellis told The Cavalier Daily that Crider agreed to the debate the prior spring, adding that he was opposed to canceling the event.

In a letter to the editor published Oct. 8, 1974, however, Crider denied she had ever told Ellis she agreed to the debate — rather, she said Ellis had reached out to ask which date she preferred for the debate to occur during Black Culture Week.

“Ironic, isn’t it?” Crider said. “To schedule a speaker on Black inferiority during a week dedicated to teaching Black achievement?”

Crider continued that the organization of the Shockley debate only demonstrated the disregard for Black students at the University in the first place.

“We, the Black students at U.Va., thought we had come a long way since the year of integration,” Crider said. “But such an incident such as Shockley serves to remind us that there is no safety in numbers — until the majority of non-Black students here are not merely aware, but sensitive to and caring of the social problems of minority students, we have accomplished nothing.”

The day after this letter appeared in The Cavalier Daily’s print edition, Ellis and his fellow tri-chairmen placed Crider on probation from the Union. In a statement to The Cavalier Daily at the time, Ellis cited “a general history of a hostile attitude to the tri-chairmen and Union committee co-chairmen” as his reasoning. Per the news article, Ellis and the other tri-chairmen had previously attempted to obtain Crider’s resignation.

Despite Crider’s testimony and the fact that BSA had asked Ellis and the Union to cancel the debate a week prior, Ellis claimed it was “impossible” for him to determine how Black students felt about the Shockley debate due to Crider’s behavior.

The contentious debate was later discussed among members of Student Council after Ellis asked the group for its recommendation on what to do. In an interview with The Cavalier Daily before the Student Council meeting, Ellis told reporters he would “probably” stand by Student Council’s recommendation.

At this time, Freeman was a Student Council representative. Today, Freeman could still recall the day he was made aware the group had been asked by Ellis to advise the Union, and remembered feeling that it was odd given that Student Council and the Union often disagreed on matters.

“I always knew where the votes were on Student Council, and I would have thought [Ellis] did, so when he showed up to ask for advice, I remember thinking ‘Uh oh, this is going to be a little bit of an opera,’” Freeman said.

Throughout a heated debate, Black Student Council representatives pleaded with their peers to urge the Union to cancel the debate and take their concerns seriously.

“I’m asking you to be responsive, to set a precedent here,” Rep. Anthony Gould said. “[This] involves the lives and dignity of a people … Put yourself in our place. I speak not because of what I have heard — I speak because of what I have experienced.”

One issue debated was whether or not the Union should be able to host Shockley given its usage of student activity fees. Per Ellis, Shockley was paid $1,000 by the Union to appear — adjusted for inflation, this equates to roughly $5,000 today. Students were also charged $1 in advance or $1.50 at the door to attend the event.

Opponents of cancelation cited freedom of speech and setting poor precedent as a major concern, with Rep. Chuck Gravett adding that the First Amendment is aimed at the dissenter.

“Nobody needs to be protected by the First Amendment if he’s spouting principles everyone agrees with,” Gravett said during the meeting.

Ultimately, Student Council advised Ellis to cancel the debate by a 13-11 vote in a one-sentence resolution.

“Student Council advises University Union Tri-Chairman and spokesman Bert Ellis to cancel the Shockley-Goldsby Debate,” the resolution read.

Despite this recommendation and Ellis’ statement that he would “probably” stand by Student Council’s advice, the Union opted to move forward with the debate.

“Citing the Union’s efforts to go through proper channels in getting Black opinion, the effects of a precedent canceling a controversial debate, and the fact that such a debate would be an academic exercise, Union Tri-Chairman and Spokesman Bert Ellis urged the Co-Chairman to not cancel the debate,” a news article appearing Oct. 10, 1974 in The Cavalier Daily reads.

Freeman remembered when he found out the Union planned to host the debate.

“I do remember having this thought — it’s always an unsettling moment when someone asks for your advice, and you already regard it as an eventuality that they will [not] take your advice,” Freeman said. “‘If you’re not going to take my advice, don’t ask for it,’ is kind of a human reaction in these kinds of situations.”

Quarles said she thought the debate would serve as one of the many things the University needed to “live down.”

“I’m disappointed,” Quarles said after the Union voted to host the debate. “I can’t say I’m surprised.”

The debate eventually took place some four months later — during the first week of Black History Month — on Feb. 5, 1975.

“I remember being shocked and disappointed that this was happening,” Green said. “It's certainly not something that I would have felt comfortable with.”

An advertisement that appeared in one of The Cavalier Daily’s print issues leading up to the debate promoted the event as “controversial.”

Per coverage before and after, the Union pre-sold 390 tickets and the event was “packed.”

“My own research leads me inescapably to the opinions that the major cause for the American Negro’s intellectual and social deficit can be traced to genetic heredity,” Shockley told the audience during the debate.

Shockley was not the first proponent of eugenics to mark University or Charlottesville history. Eugenic sentiments can be traced back to the University's founder and the nation’s third president Thomas Jefferson, who subscribed to the idea that there were scientific reasons for structural inequities between Black and white Americans.

More than 80 years later, former University president Edwin Alderman actively recruited scientists practicing eugenics from across the country, making the University a hotbed for the eugenics movement throughout the 20th century. Eugenics provided the basis for the University’s original biology department and research conducted by faculty supported discriminatory legislation such as the 1924 Racial Integrity Act, which prohibited interracial marriage, as well as the Eugenical Sterilization Act, which sterilized an estimated 7,200 to 8,300 individuals from 1924 to 1979 who were deemed “unfit” or “unworthy” to procreate.

Eugenicists at the University and statewide also provided the foundation for over 400,000 sterilizations performed in Germany under Nazi leadership during World War II. The biology department has since denounced its eugenic roots.

Today, both Green and Freeman situated the Shockley debate as one of many controversies over free speech in not just the University’s history, but also the country’s.

“I'm surprised to some extent that in our discussions of free speech at the University, we're — in this day and age — entertaining [and] allowing speakers to promote outright falsehoods like the election was stolen when in fact, it seems we dealt with those 50 years ago,” Green said. “I would have thought we would have put to rest the idea that free speech automatically entitles a speaker to espouse falsehoods.”

Free speech has been one of Ellis’ main priorities as founder of the Jefferson Council. The group’s other priorities include preserving the “Jefferson legacy,” maintaining the appearance of the Lawn as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and reinvigorating the Honor system.

Freeman emphasized that conversations surrounding free speech have continued to permeate college campuses throughout his lifetime, naming the “Unite the Right” rally as a moment that particularly shocked him given the progress he felt had occurred.

“In my lifetime, the schools were desegregated, the Vietnam War ended, Virginia votes for Obama, and then all the sudden I see these crazies marching down the Lawn right in front of my [old] room and I realize it’s still there,” Freeman said. “It’s still there.”