The events that occurred in Charlottesville both on and off Grounds in August 2017 should have taught the University community an invaluable lesson about the needs of its marginalized students. That Friday night, a group of people marched on our Grounds espousing hate and protested in downtown Charlottesville the following day, resulting in a clash with counter protesters that was extremely violent and deadly. When I learned what happened, I was only a junior in high school, still reeling from the new reality posed by former president Donald Trump’s election. I would not come to the University until two years later, and by then I had a general idea of what I could and could not expect when it came to protecting marginalized students. And now, five years after the events of Aug. 11 and 12, what I can still expect as a marginalized student is less than the bare minimum — to not feel fully safe in a space where racism has been as fundamental as it has been enduring.

Charlottesville is no stranger to providing a space for hatred to thrive. Throughout history, it has always been a stage for white supremacists to spread hateful ideology — with the University often acting as its epicenter. Throughout the past two centuries, the University community has participated in white supremacy through enslavement, slave patrols, gentrification, eugenics and much more. The white supremacists who came to the Lawn with the intent to disrupt and destroy on Aug. 11 felt comfortable doing so because their behavior was not dissimilar to what the University had not been party to in the past. The white supremacists in attendance at the “Unite the Right” rally the following day felt comfortable disrupting and destroying because their behavior was not anything Charlottesville at large had not been party to in the past.

This reality of who came that weekend and why dates back to 1924, when a statue of Robert E. Lee was erected in the historic and predominantly Black neighborhood of Vinegar Hill. At 26-feet high, the statue deifies a Confederate general and serves to intimidate Black community members. At this time, a surge in Confederate memorializations went hand in hand with rapid development happening in the City — meaning Black citizens who lived and worked where these monuments were erected faced the memory of their oppression day to day. This cruelty would not face rectification until February 2017, when City Council voted to remove the Lee statue and rename its park four months later. That was the catalyst that would eventually lead the self-described “alt-right” — an offshoot of conservatism mixing racism, white nationalism, anti-Semitism and populism — activists to plan “Unite the Right” later that year. To understand that the self-described “alt-right,” along with other groups against the removal of the statue, is to understand that they champion the same bigoted ideology as those who built these statues, as well as the individuals idolized themselves.

The “Unite the Right” rally was not an isolated event. White nationalist and white supremacist activities took place in the months leading leading up to the rally in August after “Unite the Right” organizer Jason Kessler applied for a permit for the “Unite the Right” rally in May 2017. On May 13, Richard Spencer, a University alumnus and self-described “alt-right” activist, led a Klan-esque nighttime torchlit rally in Lee Park to protest the plans to remove the Lee statue. On June 1, Kessler met with white nationalists to plan the “Unite the Right” rally. On July 8, around 50 members of a North Carolina chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, some wearing hooded white robes, chanted “white power” at Justice Park to protest the removal of the statue.

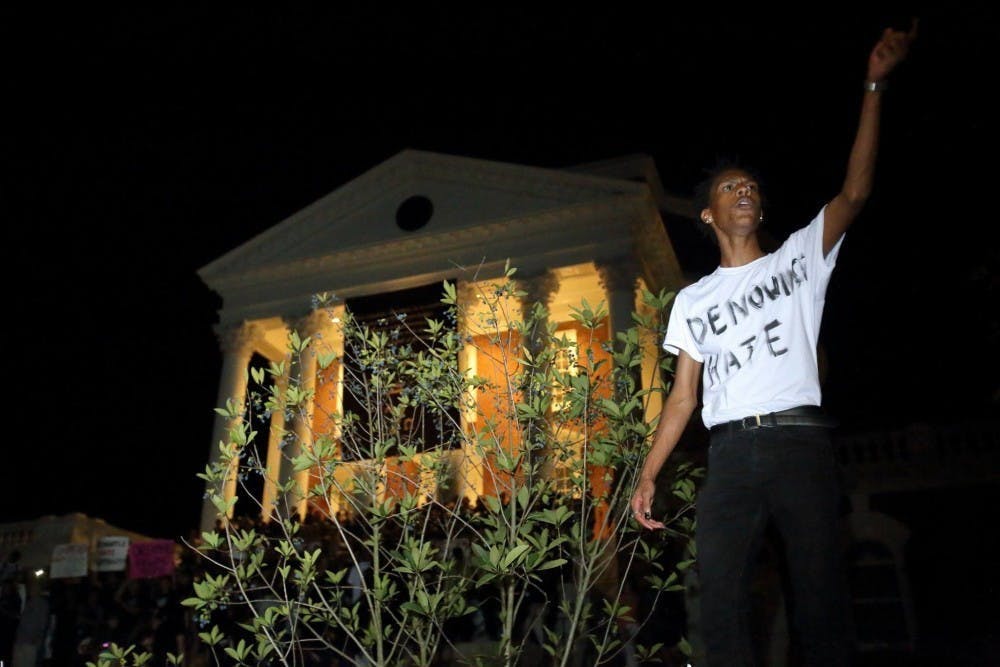

In discourse about “Unite the Right,” the lack of a clear distinction between what happened on Aug. 11 compared to Aug. 12 has led to people downplaying the effects of the tragic events. On the night of Aug. 11, 2017 Spencer would again spur throngs of racist white nationalists to march with tiki torches — this time on University Grounds while chanting anti-Semitic slogans. Though the march was planned in secret, University officials were still made aware that an event would take place hours before it occurred, and did not take proper action. A group of students would be the sole defenders locking arms around the Jefferson statue in front of the Rotunda because the University Police Department did not accept aid from Charlottesville Police Department until it was too late. The night of Aug. 11 was a small glimpse into the grim events that would occur the next day. In addition to confusion surrounding the “Unite the Right” rally location was a lack of sufficient police planning to keep protesters and counter-protesters separate. Because of discoordination between the Charlottesville Police Department and Virginia State police, differing groups clashed and the events of Aug. 12 grew increasingly violent as the day went on. Not long after the event was declared unlawful by Governor Terry McAuliffe, the already aggressive scene that had moved to the Downtown Mall turned deadly when James Fields drove into the crowd at Fourth Street and Water Street, killing Heather Heyer and injuring dozens of protestors.

After the horrifying events of Aug. 11 and 12, former University president Teresa Sullivan and Law School Dean Risa Goluboff focused efforts on improving safety at the University while consistently claiming they also wanted to heal the community. The bulk of their actual work went into impersonal actions like forming the Deans Working Group and financially backing the “Concert for Charlottesville,” for example. But what happened was not impersonal. University leaders did not take adequate action to address the social issues these events brought to light and bring comfort to its marginalized students. These social events acted as a bandaid. Meanwhile, student organizations including the Black Student Alliance, U.Va. Students United, the Minority Rights Coalition and Indian Student Association organized programming and protests to encourage meaningful discourse and collective healing. Unfortunately for marginalized students and those injured by what happened, there were other students who did not react with empathy and grace.

Grotesque comments made by some students after the events of Aug. 11 and 12 demonstrate why the University should have taken more action after “Unite the Right.” The Black Student Alliance released a list of 10 demands signed by various University groups during the “March to Reclaim Our Grounds.” Before Student Council voted to endorse the list, they held a legislative session that turned unruly when students began to debate their views on the demands. In response to one student's claim that Thomas Jefferson raped young Black girls, another responded, “And that’s absolutely awful. But, so did everyone at that time.” These kinds of comments should have been discouraged following the trauma students went through leading up to and after “Unite the Right.’”. To date, just four out of BSA’s 10 demands have been addressed. The University has removed the Confederate plaques on the Rotunda, talked about enforcing policy to restrict the use of open flames on the Lawn, acknowledged a gift to the University’s Centennial Endowment Fund from the KKK in 1921 and issued a diversity plan. But in the five years since “Unite the Right,” the University did not ban white supremacist hate groups from Grounds, they did not require education on the history of white supremacy at the University and in Charlottesville, they did not expand the Deans Working Group to include students of color and those affected by the violence of Aug. 11 and 12, they did not adequately increase the number of Black students and faculty and they have yet to properly recontextualize the Jefferson statue.

I believe a major part of the shock our community felt after the events of Aug. 11 and 12 was due to the lack of awareness when it comes to the history of race in Charlottesville. In an interview with MTV, one student described their experience dealing with white supremacists that weekend, adding that “It’s definitely fresh, at least for me, in terms of this level of open white supremacism and literal Nazism in a town that is not really used to that.” I disagree. This is a town that is very used to this kind of behavior. Black residents of Charlottesville have been dealing with bigotry from both in and out of the community for centuries. It has been a never-ending cycle that we have all had to deal with and the only reason not everyone knows about it is that many people do not educate themselves on the things that do not directly affect them. It is vital for everyone to take the time to self-educate on the history of race in Charlottesville, and more particularly at the University. Many people in our community do not know details about the history of enslavement after building the Academical Village, land appropriation in expanding the University, the student KKK chapter in the early 1920s, minstrelsy performances put on by students or the shunning of the first Black students to integrate.

The history of white supremacy and racism on-Grounds and beyond must be common knowledge for all people in the University community. After the summer of 2017, the University’s actions did bolster public safety on Grounds. It did not, however, bolster anti-racism and allyship. I believe every one of BSA’s demands were reasonable and necessary to move forward after Aug. 11 and 12. While the University has recontextualized statues, formed groups like the Racial Equity Task Force and Division for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, renamed buildings and completed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, where is the real actionable effort? Instead of forming committees, why hasn’t the University done the real work of requiring education on the values these committees uphold? We deserve to see the things marginalized students ask for be taken seriously. The physical threat revealed by “Unite the Right” was taken seriously, but the lasting effect it has had was not.

We deserve to see the University community take on the challenge of fixing not only the surface level of — what I would call — our race issue, but going deeper and doing the things that will actually matter in the long run. I demand there be required education for all students and staff on the history of race at the University. I demand the University publicly and fervently acknowledge the wrongdoings of the past that were executed both on Grounds and beyond. I demand the University require sensitivity training for all staff. I demand the University be more honest about the faults of its founder. I demand the University become a leader and not a follower that waits for other schools to make change for their marginalized students. I demand the University makes an effort to understand what it’s like to be a marginalized student occupying a space that was not built for them. I demand the University takes the time to frequently check in with its marginalized students and ask what they can do for us — and I demand they follow through.

Five years after the events of Aug. 11 and 12, our community is still not fully healed. Every single member of the University community has a role to play in acknowledging that this is not the first or the last time something like this could happen at the University. I know that as a student, it is my responsibility to be aware of the needs of my peers and stay knowledgeable of the socio-cultural state at the University. Our professors’ responsibility is to do the same and advocate for a safer, more comfortable environment for students. The responsibility of University leaders is to enforce change that will make marginalized students more comfortable and advance the landscape of cultural understanding at the University. After installing a small marker next to the Rotunda in 2007, it took administration nine years to adequately commemorate the lives of the enslaved laborers who built the University by erecting the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. I hope they will have a greater sense of urgency moving forward and not wait to take sufficient action until it is indecent to no longer do so.

In order to properly move forward together, there needs to be a base understanding of the experience of marginalized students at the University. I personally do not feel safe most of the time when I am both on and off Grounds. I am constantly waiting for something outlandish to happen because the reality is that racists spouting hate speech could come here and put me in danger. I would implore everyone in a place of power at the University to put themselves in our shoes and try to begin to understand our fears. Understanding our pleas means understanding that building a memorial and renaming some buildings is not an end all be all — it’s a band aid. Understanding us is to understand that it’s way past time to do things out of one's comfort zone. It is way past time to inconvenience oneself and get comfortable making the kind of change that really matters. Because not doing so is telling the marginalized students in this community that they do not matter enough to make yourself even a little bit as uncomfortable as they are every day. We need University leaders to act with the same sense of urgency that is felt as a marginalized student on Grounds.

In order to properly move forward together, our community needs to think about and answer some tough questions — why do marginalized students always have to plead for help? Why are their demands not being met? Why does the University continue to rest in its comfortability at the expense of its marginalized students’ well-being? And most importantly, we must ask ourselves — has anything been learned from “Unite the Right?” I can only hope that the five year anniversary of “Unite the Right” will be the necessary call to action our community needs. Marginalized students can only do so much in healing our community, so we need everyone else on board. What happened on Aug. 11 and 12 was not a threat that came and left — it is a prevailing disease that has yet to be fully healed. The lack of urgency has sent a clear message that the University does not value its marginalized students enough to make valuable change. It should not take five years to understand that what we need is a necessity.

Aliyah D. White is an Opinion Columnist for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.