In 1875, on a warm July day, the great poet Antonio Machado was born in Seville, Spain, in a stone building crawling with ivy. He died 63 years later in 1939 in France, one of thousands of Spanish citizens — many of them great writers, poets, musicians and artists — forced out of their homeland during the Spanish Civil War.

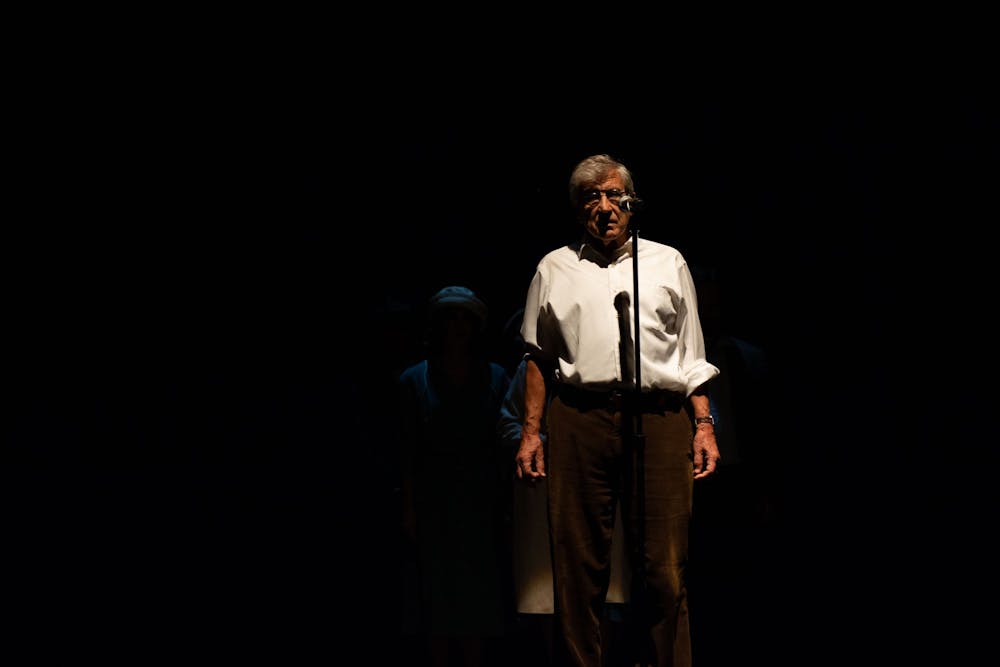

Machado’s life — his birth in Seville, travels to Europe to teach and write, the pain of his exile in Paris and eventual death in France — was brought to life Friday evening at the Paramount Theater in the Spanish Theater Group’s performance of “Flamenco y Exilio.”

Written by Asst. Spanish Prof. Fernando Valverde and directed by Spanish Prof. Fernando Operé, “Flamenco y Exilio” wove Machado’s story with flamenco performances from singer Juan Pinilla and guitarist David Caro, both of whom traveled to Charlottesville from Granada, Spain for the performance.

The Spanish Theater Group was founded in 1981 by Operé, who has directed over 52 plays since the group’s conception. He said that the performance was inspired by one of the main issues in the world today — individuals who still live in exile, who have had to leave their homeland to escape or in search of a better life. Charlottesville itself is home to 4,600 refugees from 32 countries around the world.

“Fundamentally [the show] is the relationship between flamenco and exile, because flamenco was also the music of the marginal[ized] people in Spain,” Operé said. “This is a tribute, in some way, to all of these people living in exile.”

The roots of flamenco music lie with the Andalusian Roma people of Southern Spain, a group who migrated to Spain between the 9th and 14th centuries. While often associated with flamenco dance, the guitarist and singer of flamenco are often the heart and soul of the performance.

Narrators Melissa Frost, Alicia López-Operé, Mercedes Herrero and Chad Freckmann told the story of Machado’s life interspersed with performances by Caro and Pinilla, many of which were Machado’s poems set to original music. The music, Operé said, was the most important part of the event — third-year Engineering student Madelyn Khoury, a student in Operé’s contemporary poetry class, agreed.

“It was really impressive to me — not only the stamina and skill of the musicians, but also the raw emotion,” Khoury said. “There were times when I could hear the pain, the cracks in his voice and it really just added so much to the performance.”

Some of the most emotional moments of the evening — Machado’s death, for example, as he lies in his sickbed with his ailing mother beside him — were underscored with both guitar and powerful, wrenching performances from Pinilla.

While the performance was done entirely in Spanish, students in three sections of Spanish translation classes translated all of the sections of narration, the songs and the poems for English speakers to follow along with on their phones. Third-year College student William Joyce worked with a small group to translate both a poem and piece of narration, and said there were unique challenges with each.

“There's some liberty and how you translate [the narration], but ultimately the ideas that you're translating are pretty concrete,” Joyce said. “[With the poem], not only is the Spanish more nuanced, but ideas are more complex and harder to grab.”

The performance lasted almost two hours, detailing Macahado’s travels to Castilla, his marriage to a young woman named Leonor, his service as a professor at the French Department of the Technical Institute in Segovia, Spain and the Civil War which broke out in Spain in 1936.

“We are on the side of the government, the Republic and the people,” Machado wrote in a newspaper published July 31, 1936, as themes of loss and uprooting began to develop in his poetry. “Spain is split asunder,” the narrators read.

The final part of the performance featured ten actors, each of whom played a “Voice of the Exiled” — poets, writers and actors who fled from Spain at the outbreak of war, many of whom never returned to their homeland.

“A fatherland, a modest land, like a treasured courtyard or a crevice in an ever-sturdy wall,” the voice of María Teresa León said of her search for belonging following her departure from Spain. “A homeland to replace the one that was mercilessly torn from my soul.”