By April 1, the University will release decisions for the remaining class of 2028 applicants. For Yale, Dartmouth, Brown and a growing number of other universities across the country, this admissions process marks the final cycle before returning to standardized testing requirements. One year ago, the 134th Editorial Board urged the University to maintain their no-testing policy indefinitely — citing both the test’s problematic origins and its ineffectiveness at evaluating prospective students. While we do share the concerns voiced by the previous Editorial Board, our current moment is different. We now believe that standardized testing has a place in the future of college admissions, provided it is considered within the larger context of an applicant’s abilities and circumstances.

Debates around standardized tests have lingered in academic circles for years. Critics of testing have long pointed out that scores often run along socioeconomic lines, with wealthier students possessing the resources necessary for private tutors and prep-classes. But it was not until the pandemic that real change occurred. COVID-19 left many students unable to reach testing locations, and as a result, colleges and universities took their first steps away from standardized testing, shifting to test-optional policies. While the impetus for the change may have been convenience, test-optional policies became a matter of equity that transcended the pandemic.

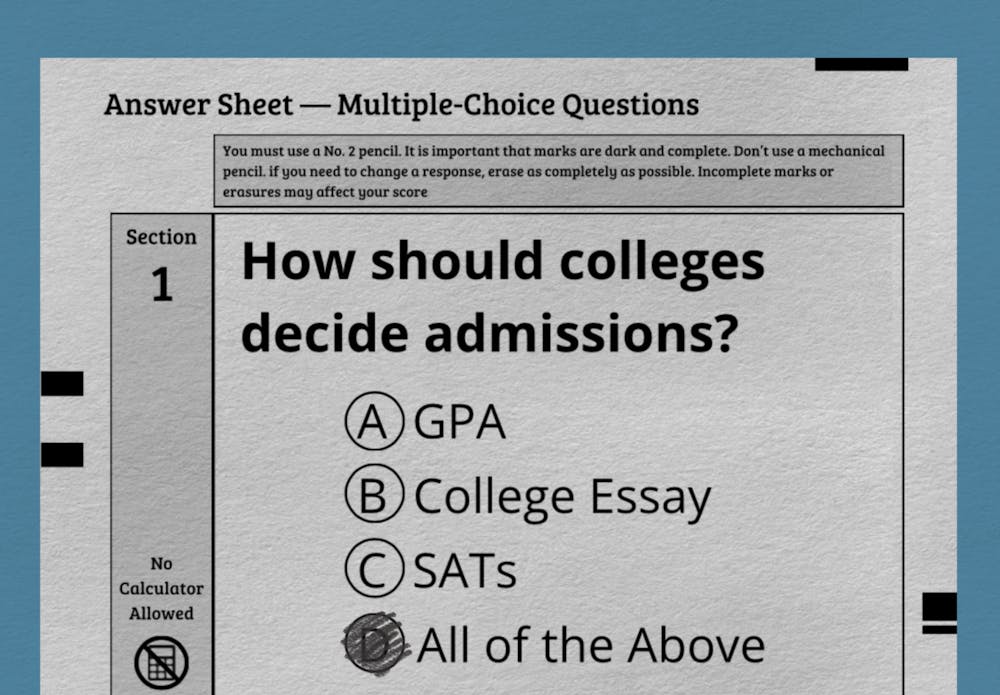

With test-optional policies widely in effect, admissions offices relied more heavily on other factors to make their decisions, including a student’s GPA, college essays, extracurriculars and recommendations. While these may have seemed to provide admissions officers with less biased means of evaluating candidates, many of these methods of evaluation have merely manifested the same equity problems that were found in standardized testing. Consider GPAs — as testing became less and less prevalent, grade inflation increased, particularly at wealthier high schools. Facing pressure to maintain their staggering matriculation rates into the top universities, wealthy high schools skewed grades by grading more leniently. Moreover, GPA has largely been acknowledged as an unreliable factor in predicting student success in college. Next, consider college essays — much like how students could hire tutors to prep them for the exam, wealthier students can choose their pick of countless college essay advisors. The college essay has been further discredited by the rise of artificial intelligence like ChatGPT which may assist students in writing their college essays. These are two prime examples of how the tools with which admissions offices make decisions have become largely ineffective in predicting student success and are also imbricated in systems of privilege.

It is not that GPA and college essays should be scrapped from the admissions process. However, the problems that admissions offices sought to solve by extending test-optional policies are as prevalent as ever, just in a different form. In fact, getting rid of standardized testing has, in some ways, enabled admissions offices to deflect criticism about other methods of evaluating applicants. Universities have neglected the manner in which the college admissions process is systematically structured to give students with more resources a leg up. Getting rid of standardized testing did not solve those problems. If it is our goal to make college admissions as equitable as possible, then admissions processes must take all factors into consideration — and that includes standardized testing.

Okay, we know how that sounds — and by no means are we advocating a return to pre-pandemic admissions processes. But what has become increasingly clear is that much of the problem with pre-pandemic standardized testing was located not just in the test itself but also in how the test was used by admissions offices. Standardized tests were hailed as an objective measure of scholarship and aptitude. But this process took numbers at face value and, as such, was never a truly objective process. A successful return to standardized testing is contingent on how testing is reimplemented into and evaluated during the admissions processes.

This means that comparisons must be made between similar applicants, in addition to other factors. For example, Dartmouth College, one of the first colleges to bring back standardized testing, considers scores in the context of a student’s environment. In short, admissions offices must take into account socioeconomic and geographic score discrepancies in order to gain a complete and nuanced understanding of an applicant’s aptitude and scholarship. Provided that tests are implemented in this way at the University, they could become one of the more reliable and equitable predictors of student success. Therefore, should the University bring back testing, it must adopt similarly holistic policies.

New conversations surrounding standardized testing suggest that admissions offices have a chance to re-implement standardized testing in a way that increases accessibility and critically engages with the nature of university admissions and the contemporary problems it faces. The reimplementation of standardized testing should be recognized as a single step towards a more holistic and equitable admissions process. For this step to be more than a superficial change, admissions offices must use standardized tests as a way to begin addressing the more systemic issues that undergird the entire admissions process.

The Cavalier Daily Editorial Board is composed of the Executive Editor, the Editor-in-Chief, the two Opinion Editors, their Senior Associates and an Opinion Columnist. The board can be reached at eb@cavalierdaily.com.