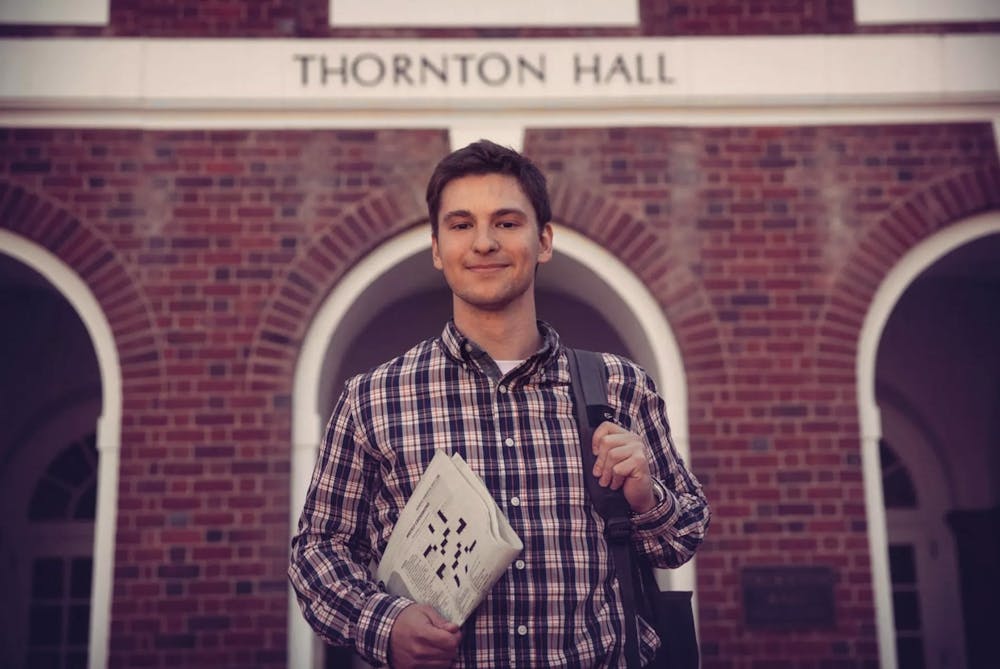

Sam Ezersky, a digital puzzles editor for The New York Times and Class of 2017 alumnus, experienced a whirlwind journey from being a puzzle staffer at The Cavalier Daily to editing puzzles in the Big Apple. Ezersky currently edits The New York Times’ digital Spelling Bee, a game where solvers spell as many words as they can with only seven letters. A long time puzzle aficionado, Ezersky is passionate about making newspaper puzzles modern, fresh games for anyone to enjoy.

In his day-to-day work, Ezersky evaluates the difficulty, accuracy and style of Spelling Bee puzzles, and he also reviews hundreds of crosswords submitted for publication in The New York Times’ Games section. He describes editing as a process of fine-tuning. Each time he crafts a crossword clue or tweaks a Spelling Bee grid, he strives for the Goldilocks zone — a puzzle that is not too easy nor too difficult — engaging puzzle solvers of any skill level.

“My overarching tenet … is really keeping in mind our widespread audience,” Ezersky said. “I truly want to be able to offer something for everybody.”

Long before he became an accomplished editor, Ezersky was a child fascinated by the way words fit inside a grid. He remembers his earliest encounter with puzzles at age five. While waiting in a barbershop for his brother to finish getting his haircut, Ezersky picked up a magazine and stumbled upon fill-it-in puzzles — puzzles similar to crosswords, but with a word bank rather than a set of clues.

“[It was] truly love at first sight. I don't know if I did a particularly good job — I just remember diving right into it … and being interested in how [puzzles] all come together,” Ezersky said.

Ezersky’s interest in puzzles continued to grow as he moved beyond merely completing puzzles and began to create his own. Ezersky sold his first crossword to The New York Times in high school, and he started competing in the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament — the nation's oldest crossword competition where solvers tackle eight original crosswords over two days. Ezersky said that by then he had discovered the secret to solving crosswords.

“The real secret of solving crosswords is [that] you see the same answers over and over again … It's a lot of pattern recognition, rather than knowing a bunch of trivia,” Ezersky said. “Puzzles have historically gotten the rap of being this erudite game. How smart are you? How cultured are you? But I think all puzzles are just a daily or weekly way to scratch your brain.”

Between doing his mechanical engineering and economics homework, Ezersky created crosswords for The Cavalier Daily. His popular puzzles made him a local celebrity on Yik Yak — an anonymous social media app for college students — where his fellow students responded enthusiastically to his crosswords. However, puzzles were not on his radar as a potential career — instead, he planned to go into engineering.

Ezersky’s perspective changed at the end of his third year when he came to a serendipitous crossroads. He reconnected with Will Shortz, crossword editor at The New York Times and Class of 1977 alumnus, after Shortz had delivered a keynote speech at the School of Law commencement ceremony in May 2016. The two had met before at the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, and Ezersky took a chance to rekindle a conversation with his idol of the puzzle world.

“I decided on a total whim, YOLO, I just shot him an email,” Ezersky said. “He came to my gross house off JPA with a six pack of Corona. He sat down and we just talked puzzles for hours.”

The two kept in contact and would even solve puzzles together during Ezersky’s summer and winter breaks. Ezersky eventually assumed a contractor position at The New York Times after he graduated in 2017, which quickly turned into a full-time position editing crosswords. In 2018, Ezersky spearheaded the digital reboot of the Spelling Bee game, the brainchild of Shortz himself, which had been running weekly in The New York Times Magazine since the mid-2010s.

Ezersky reflected on how the role of puzzles fits into journalism in his conversation with The Cavalier Daily.

“It is really cool to be able to contribute to media like this. You have your stories, your columns and your culture, and then you have a game to tie it all together,” Ezersky said.

Ezersky touches the lives of millions of people around the world through his puzzles. Many readers now incorporate Spelling Bee and the Daily Crossword into their daily routines. University students are no exception — across Grounds, The New York Times’ puzzles are often seen on laptops or phones, sprinkled across lecture halls and libraries. For Ezersky, the exponential growth of Spelling Bee’s popularity in the past few years, especially during the pandemic, affirmed his long-standing passion for puzzles.

“As the goofy bashful teenager, this was my deep, dark secret,” Ezersky said. “I was the kid sitting in the … lecture, just working on crosswords in the back … little did I know it would jumpstart me into the industry [that] I'm in now.”

Ezersky insists that puzzles, regardless of their level of difficulty, can offer something for anyone. In the future, he hopes that varied perspectives and experiences among puzzle creators will help increase the reach and accessibility of puzzles.

“If we want to be able to say that we're catering to some widespread audience, it all starts with actually having a bunch of widespread perspectives across the room,” Ezersky said. “It's really beautiful to just see that happening in a sphere like puzzles as it continues to echo what's going on in the real world.”