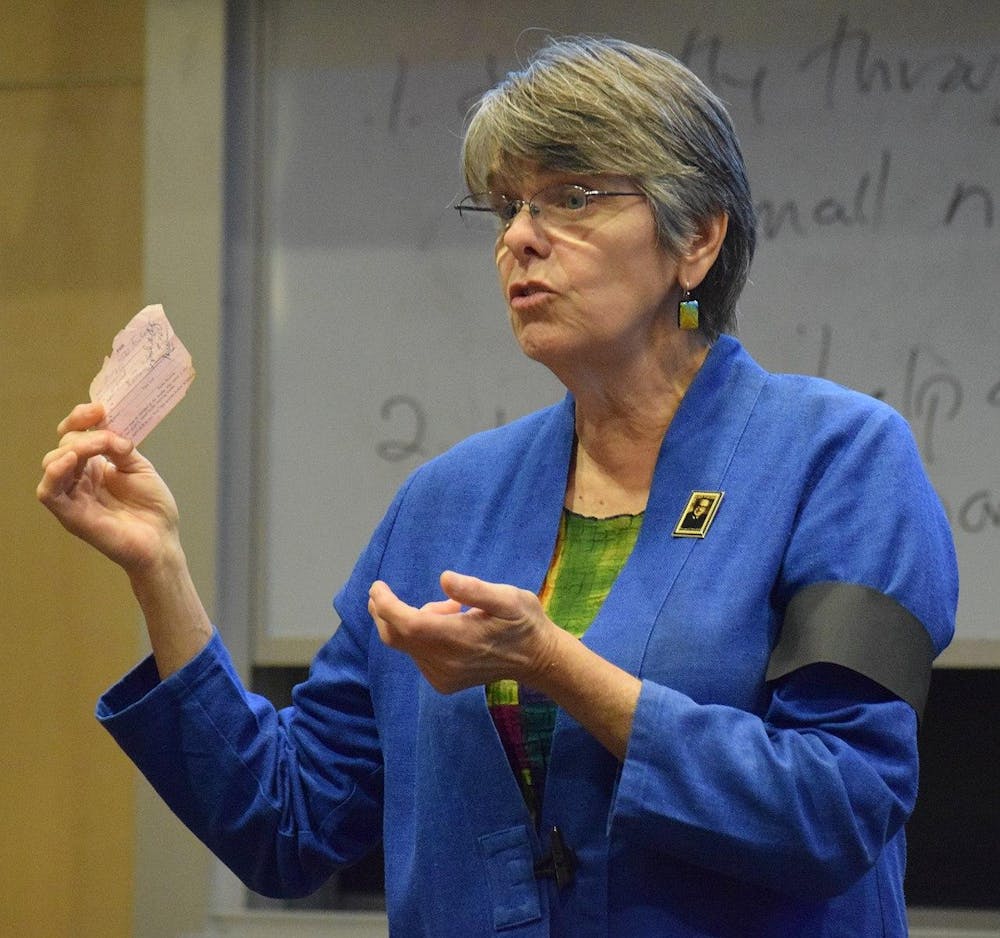

Mary Beth Tinker, the plaintiff of historic Supreme Court case “Tinker v. Des Moines,” spoke on Grounds as part of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society’s Distinguished Speaker Series Friday. During the speech, titled “Academic Freedom in a Time of Book Bans and ‘Plausible Genocide’ in Gaza,” Tinker spoke about her experiences before and during the landmark case, the importance of freedom of speech and the importance of youth activism in relation to current events.

In 1965, Tinker and fellow students wore a black armbands in school to protest the Vietnam War. After her school suspended her in order to uphold their “school discipline,” Tinker took the Des Moines Independent Community School District to court for violating her First Amendment right to expression.

The Supreme Court ultimately ruled in Tinker’s favor in 1969, stating that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression” within schools. The case had far-reaching implications, opening the door for protests and political speech within schools, such as the protests led by University students against expansion of the Vietnam War in 1970.

Tinker, who had been surrounded by social and political activism even before the Supreme Court case, went on to become a nurse and continued to promote civic education and student rights throughout the course of her career. Most recently, she has done this through virtual speeches via the Tinker Tour, a project by the Student Press Law Center that organizes speaking events around the country.

Tinker’s observations as an activist against the Vietnam War have been relevant to her advocacy work today. During the talk, she drew parallels between the American public’s attitudes towards events in the Middle East today and events in Vietnam in the 1960s.

“Most Americans didn't even know where Vietnam was, they couldn't find it on a map,” Tinker said. “They didn't know the history of the country, that it had been a colony … Americans don’t know what it's like now. Americans don't know Gaza, they don't know the West Bank. They don't know the history… and that this didn't start Oct. 7.”

While expressing her stance against the current violence in the West Bank, Tinker also emphasized the need for respectful civil discourse and empathy for differing opinions as a free speech advocate. From issues ranging from Israel and Palestine to book banning controversies, Tinker said tolerance and expression have grown to be important components in her philosophy towards activism.

“We can't sweep things under the rug that are controversial,” Tinker said. “It says right in the Tinker ruling … some things are going to make us uncomfortable to talk about, but we must talk about these things, or we don't have education and we don't have democracy. So we have to be able to talk about controversial things.”

Tinker said her parents’ advocacy efforts influenced her values and beliefs around activism and freedom growing up, telling a story of her father, who was fired from his position as a reverend due to his open support of a desegregation effort at a local public pool.

“Some of the kids at the church said, ‘Reverend Tinker, we should change [the segregation policy], that’s not fair and that's not very loving,’” Tinker said. “Adults often say, ‘well, that's the way it's always been, life's not fair, get used to it.’ Well, they didn't get used to it. … They decided to use their First Amendment rights to speak up about those things. That's the way that I was raised.”

As she entered her early teenage years, Tinker said she became increasingly concerned with social justice, including civil rights advocacy and, notably, anti-war activism. Tinker gave the audience an inside look at the story behind the black armbands, which she said was inspired by James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin, who originally wore them to commemorate lives lost to racist violence in the Birmingham, Alabama church bombings. She said that as a result of the “Tinker v. Des Moines” decision, youth were afforded more freedom in expressing their frustration and anger about issues of injustice.

“The Tinker case that was decided a few years later, it's about youth having the right to express all the full range of human emotion,” Tinker said. “Not just the happy feelings, no, the full range: grief, anxiety, depression, sadness, sorrow, whatever it is. You should have a right to express those feelings, and we had all those feelings when we heard what happened to the Birmingham children.”

According to Tinker, the emotionality that fuels activism is a strength of young people. She said she has sourced inspiration from the courage and boldness of young advocates who channel frustration into action, citing this as part of the reason she is dedicated to youth rights.

The event ended with a question and answer session, during which Tinker answered students’ questions which ranged from inquiring about her personal experiences as a civil rights advocate to her opinions on social media’s impact on activism. In keeping with the spirit of free speech and expression, Tinker invited students in the audience to answer the questions they had posed for her, engaging in several conversations with them up until the end of the event.