Life brings things like illnesses, religious events and family emergencies — all of which seem like reasonable excuses to occasionally miss a class. Yet, here at the University, professors have license to enforce 100 percent attendance policies, meaning if students miss a single class, their grade may be jeopardized. While absences for religious holidays and illnesses are traditionally accommodated by professors, there is no institutional guarantee for accommodation. Because mandatory attendance policies harm student health and learning, the University has a responsibility to reform their attendance policies to encourage greater flexibility and promote student learning.

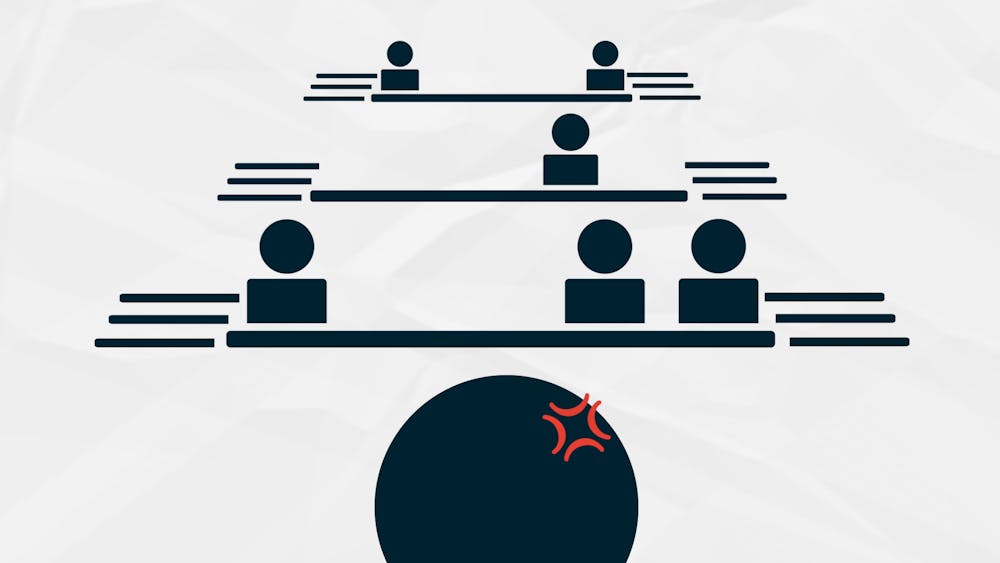

While attendance policies do vary from class to class, the University permits professors to enforce mandatory attendance policies. Let me be clear — the problem here is not what attendance policies professors choose to enforce but rather the fact that should professors choose, the University has given them cover to adopt inflexible and totalitarian attendance policies. Under such policies, whether or not an absence is worthy of being excused is completely up to the discretion of professors. And despite students who have written about this again and again, the University has not taken formal steps to embrace more compassionate attendance policies.

Beyond student objections, the University’s institutional attendance policies have the capacity to dangerously impact students and the community. Consider illness as an example — while professors are theoretically accommodating of illness even under strict attendance policies, the presence of strict policies frequently lead students to feel pressure to attend class even when ill. The pandemic proved that having sick students attend class is catastrophic, and yet too many students still feel pressured to push through and attend class while sick, which only further spreads illness. In short, the University’s claims that students should simply stay home when symptomatic are often out of step with the University’s baseline attendance policies which create pressure on students to attend class despite sickness.

Mandatory attendance policies may be well intentioned. After all, regular class attendance has a well-documented history of benefits ranging from helping students better understand course concepts to helping students form a better sense of connection with their peers. However, there is also clear evidence that does not support the idea that compulsory attendance policies cause better academic performance. Multiple studies even found there to be a negative relationship between the two.

In fact, inflexible attendance policies actually reduce student buy-in to their own learning and diminish their academic outcomes. Research indicates that classes with mandatory attendance can be demotivating to students because student motivation is linked to their sense of agency. Furthermore, making a class more challenging through additional stringent attendance requirements only adds to its “logistical rigor” but does not necessarily impact how much or how well a topic was learned. If the University’s goal is to ensure that students are learning material in rigorous classes, then mandatory attendance policies are not a necessary step. In fact, they are a misstep.

Learning is nuanced and difficult to quantify, and while attendance can be one indicator of how well a student engaged with the material, there are other metrics of that including skill level, improvement on material and participation within a class. In short, overly stringent attendance policies, in general, are harmful to students. Mandatory attendance policies are a prime example of a policy that is too strict — they remove student agency from education and can make what could have been a formative educational experience a frustrating one instead.

Luckily, there are simple solutions some professors implement to treat students as adults with the agency they deserve. Professors at the University and beyond choose to employ a “token” or make-up policy. In these policies, students are given an allotted number of absences and have opportunities to make up absences through engaging in educational opportunities relating to content taught within the classroom. Implementing this within class syllabi empowers students to make choices about their own educational journeys. For example, a sick student would stay home if they are experiencing symptoms, which could help speed up their recovery process and prevent spread of illness. Policies such as these give students and professors freedom to let the messiness of life such as illness and sudden events occur while promoting learning in and out of the classroom.

University students attend this school to further their learning. But with the possibility for antiquated, inflexible attendance policies, the University enables the intrinsic motivation central to this community to be stolen from its students. Creating institutional safeguards to ensure greater leniency towards absences could enhance student learning and empower students to take charge of their own education.

Julie Harbath is a viewpoint writer who writes about university life for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.