Currently illuminating the dark corners of the Fralin Museum of Art is “Barbara Hammer: Evidentiary Bodies,” a vivid exhibition exploring what it means to make art in the midst of severe illness. Hammer, an experimental filmmaker known primarily for her innovative work within the feminist and queer film genres, dealt with ovarian cancer for the last 13 years of her life. The exhibit, unveiled at the museum June 22, features the short film “Evidentiary Bodies,” her last before passing away in 2019.

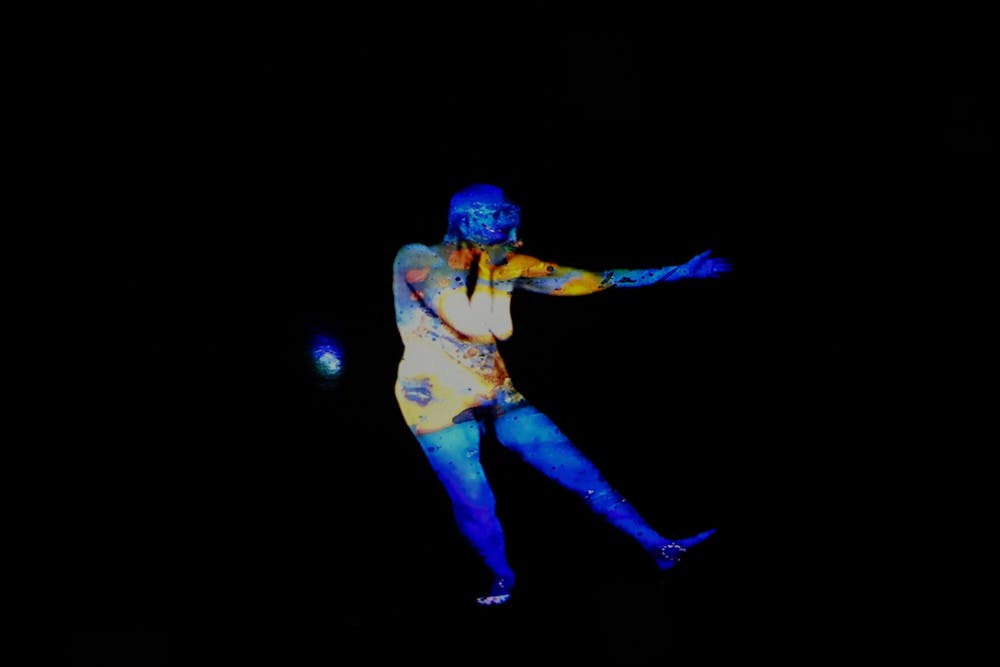

The installation uses small transmission screens and large scale video projections to display Hammer’s own medical X-rays alongside “Evidentiary Bodies,” a video amalgamation of images from her past films, footage of her moving body as well as bright and abstract shapes resembling photography prints.

Created in 2018, the film serves as an extension of her 2016 live studio art performance of the same name at the Microscope Gallery and The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. Though people will often describe cancer as a “battle,” Hammer explicitly rejected that phrase in that performance, calling it “misleading and wrong” on her website. She specified instead that “cancer is not a ‘battle,’ cancer is a disease.” Both the 2016 performance and the film currently housed in the Fralin represent Hammer’s commitment to “living a vital life” with disease, not in spite of it.

Along with being emotionally compelling, the exhibition is also physically immersive, according to M. Jordan Love, the Carol R. Angle academic curator and co-interim director at the Fralin. She encourages everyone to go to the installation to experience how powerful multimedia, immersive art can be.

“Immersive experience is really just on a fundamental level, very sensory, and so that in itself can just be a really fascinating and interesting and sometimes magical experience,” Love said.

This sensory captivation starts as soon as museumgoers enter the exhibit. Transmission screens displaying Hammer’s X-rays hang from an entryway, grouped together in clusters that give the distinct appearance of curtains. There is no way to pass through to the next room without touching those X-rays, a curatorial decision that forces observers to really engage with the palpable nature of another person’s illness.

“It’s experiential. She’s tapping into all of our senses,” Love said.

Along with sight and touch, the exhibit also engages the sense of sound, utilizing the original cello music of Norman Scott Johnson, a friend and collaborator of Hammer. After viewers pass through the X-rays, they enter a large room with three projections on three separate walls, displaying the film of “Evidentiary Bodies,” which is soundtracked by Johnson’s music.

The cello varies in speed and volume alongside various iterations of videos of Hammer crawling, dancing and walking through space alternately colorful and dark. A striking moment shows two images of Hammer — one clothed in a white bodysuit, one naked. The two renderings of Hammer weave in and out of each other, never fully overlapping or separating.

For Ainsley McGowan, Fralin Student Docent and third-year College student, the display of this intimate imagery is extremely meaningful. McGowan said that the level of vulnerability embedded in the exhibit is what makes it so impactful for those who interact with it.

“This is such an intensely personal process, that she’s chosen to share with us, because it gave her some bit of comfort during [life with cancer],” McGowan said.

As a student in the Docent program — which trains University students to lead educational tours for school aged children through the museum — McGowan has been able to introduce young students to Hammer’s work. While the task seems daunting because of the topics of illness and mortality on which the exhibit is based, McGowan shared that kids are often able to handle and process the subject matter better than adults would expect.

“Even if you take a kid into the Barbara Hammer exhibit, maybe they haven't experienced it firsthand, but maybe they visited [a loved one] in the hospital. They have some relationships. If you give them breadcrumbs, or ask them questions, they can make connections.”

McGowan said that the multimedia interplay of this exhibition — from the cello to the colors to the screens — not only makes the installation engaging and accessible for children but also highlights the overall diversity and range of work featured in the museum.

“People don't really realize how extensive our collection is, having [the installation] on the first floor is really good to show people that are walking into the museum and looking around, ‘Oh, there's more here than I realized’,” McGowan said.

To further engage the community with Hammer’s work, the extracurricular U.Va. School of Medicine organization HeArt of Medicine will lead a workshop in the exhibition Oct. 7. The group facilitates conversations and workshops with various experts who deal with issues of death, in order to help med school students develop empathetic bedside manner.

“[The organization comes to the Fralin] at least once a year, to look at art, to talk about death and dying, because art is a good medium,” Love said. “You can talk about the art itself without having to first go through some of the difficult conversations around your own experience … it'll be a great way for the nursing and medical school students to see that view through the artist’s eyes.”

“Evidentiary Bodies” reminds us that fruitful and compelling work can come from life’s unexpected turns. According to Love, with this exhibition, the Fralin spotlights a consistently innovative artist, a woman whose historically visionary film work is still shaping the current generation.

“Barbara Hammer is no longer with us, but current artists are building off of her work. So it's important for us to recognize where film art has come from, where it is now, and where it's going,” Love said.

“Barbara Hammer: Evidentiary Bodies” will run at the Fralin Museum through January 26, 2025. The Fralin is open every day except Monday, and daily hours of operations can be found on their website. Admission to the museum is always free.